Ghana: The African who wanted to be a detective

The Other side with Nathaniel Manheru —

Dear reader, if you expect a straight piece this week, prepare for a shocker. I want us to construct meaning from a knowledge-spawning situation I came across in one of my intellectual peregrinations.

This week iwe neni tine basa. We have a job to do, jointly. An epistemological job. A key African African-American figure in the era of resurgent African nationalism was Richard Wright, a writer. For me Wright has always been important insofar as he personified the ambiguities of colour-based solidarity in human struggles.

The writer of a “Native Son” makes you reconceptualise race. I don’t know how my columns impact on white readers, but I would hate it if my argument, so laboriously kneaded, so copiously illustrated, would boil down to simple black-white, dichotomous diatribes, themselves part of the baneful racial chauvinism I so wholeheartedly disdain, I received, willy-nilly, from British colonialism. That would not make me a better person, better than the legacy inherited from colonial exposure.

The struggle nuances

Let’s face it, the best antidote against white racism cannot be anti-racist racism, which is why the philosophy of our armed liberation struggle put accent on smashing the racial colonial system, never on a genocidal elimination of whites as a race. Not that whites were not a legitimate target. Only some, specifically those who served the system.

Of course while it is a fact that the Rhodesian racial ethos totalising racism; a fact of colonial Rhodesia that virtually every white man and woman supported and profited from colonial racism as a system of dominance and occupation, but having a more nuanced view of the struggle, nuances beyond the race dialectic, enabled a gun-wielding cadre to embrace an Irish-white Bishop Donald Lamont who fought UDI, while eliminating on sight a Shona-black Muzvondiwa who fought on the side of, and thus served racist white colonial Rhodesia.

It is instructive that in place of white/black dichotomy, the lexicon of struggle richly included derogatory terms like “mapuruvheya”, “Capricorn”, “murungumutema”, “chighananda” and many some such pronominal terms that showed reality was a lot more intricate, entangled, than black/white.

One Cde Elias Hondo

I quite like the point Cde Elias Hondo made to The Sunday Mail two or so weeks ago in an interview in which he recalled how ideological training for the struggle included warnings on the spectre of know-it-all, African lumpen recruit elements who sought to stick out, who saw the struggle as some kind of moral-free adventure in which anything would go.

Always seemingly better educated and more sophisticated, these urban recruits were harder to tame through training, harder to discipline through command. Added Cde Hondo: we have them in ZANU-PF nowadays and they have been responsible for much confusion in the party. His real point was that even trained cadres could still pose a real threat to the broad objectives of the struggle than say non-armed white fence sitters.

Hence the notions of “murungumutema” – the white-blackman, and chighananda, the black petit bourgeois. Amilcar Cabral devoted a whole chunk of his ideological lecturers to that very matter which he confessed was and is sure to vex any revolution. For more information, read his “Unity and Struggle”, a must-read for progressive Africans.

The cat that looks through a tunnel

Put differently, I see not much difference between a cat that looks down a barrow where mice “house” and play, on one end, and a mouse that looks up the same barrow the mouth of which passes for a lense through which it espies feline danger when it lurks and prowls, on the other. Both – killer and victim – share this one narrow tunnel that trims down sight and vision, that narrows what otherwise would have been a vast vista for them to enjoy many other possibilities.

For, save by rule and tyranny of instinct and tradition, there is nothing that deems, trims and summarises the cat/mouse relationship into gnarled paws and terrific dashes into the subterranean, respectively. Except for predatory instinct, the cat need not always pounce. Except for self-preservation instinct, the mice need not always dart and dash for safety. Freed from the tyranny of instinct and tradition, there could be more possibilities between these two than their immemorial enmity.

Maybe the mouse would have taught the cat how nests are prepared, before litter is made and dropped. Or how nuts are tastily enjoyed long before that human woman laboriously bends down to crush and grind nuts for fine butter. And poor cat, the sweet result is soon bottled and screwed well beyond the cat’s reach and ability to un-screw.

. . . and the mouse that looks up a tunnel

Or by reversing the equation, maybe the cat would have taught the mouse how easy and simple mewing secures better human goodwill and a bowl of milk than those dangerous, nocturnal pilfering expeditions, often betrayed by chaotic squeaks in the barrow, warren or sooty thatches, squeaks which then invite oversized, deadly whiplashes from the farmer’s angry wife. I mean what longer lives mice would enjoy, if only they mewed for nuts, in place of that ugly, squeaky jeer after a destructive pilfer!

All these veritable possibilities, the tradition of parochial cat/mouse enmity discounts, making both parties all the poorer, sadly with neither knowing it. It is narrowness; it is blindness. A double bane which only the folkloric age ever beat. For African folklore tell us time once was when cat and mouse sat amicably together, all to discuss and settle problems of the village. So anti-racist racism cannot be a sound response to white racism. Which is why I have never wanted to organise my world-view around the race/colour binary. And Richard Wright fortifies me in that belief. Here is how.

The age of colour, race

The early part of the 20th century saw Africans organising their struggles around the easy dialectic of colour and race. This was quite understandable. Slavery had seen a hard-to-describe outrage, seemingly against the black race, and one seemingly perpetrated by the white race. Colonialism had seen the conquest and occupation, seemingly, of a people – of a race, of a colour – again seemingly by an imperious white race.

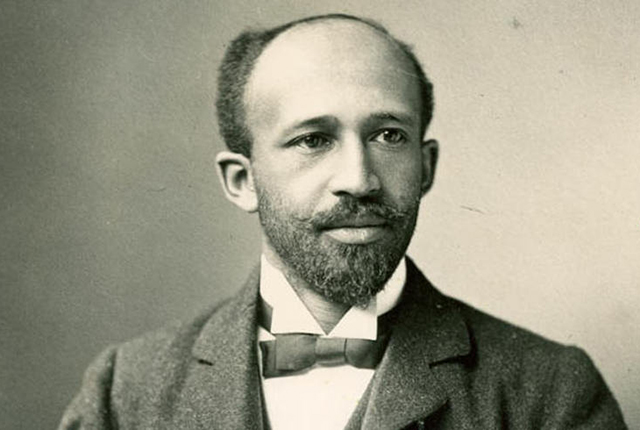

Who would begrudge blacks and Africans for capsulising their woes in the colour white, reposing all their redemptive hopes in the colour black? Who? In the wake of such a bi-focal colour prism, a whole scholarship was born, with the likes of Du Bois decreeing that the great question of the 20th century would be that of colour. The decree caught on, infecting the black world into a tri-continental movement of an offended and agitated race.

Gentle reader, I don’t need to remind you of the Genesis and growth of Garveyism, Pan-Africanism, Negritude and many other sibling movements and ideas through which affinities were formed around colour and race, indeed through which a broad, Pan-Black, Pan-African, Pan-Colour, Pan-Race family was imagined, sang, romanticised and even ritualised through periodic, transcending jihads, conferences and festivals.

When matters all seem

I am a very nuanced user of the queen’s language. I am alive to words and their meanings, very alive to careful diction in the construction of intended meaning. And in eliciting desired reader responses. You squeaked at my use of the word “seeming”. I fully understand. It is as if this is one big slavery and colonial apologia. But get me straight, the word “seeming” was not used in a fit of stylistic absent-minded recklessness. No. It was consciously used, used advisedly.

The French talk of “les most juste” – the right word in the right place. Excuse my poor French and, please correct me in your posts, hopefully without abusing me. I write this piece well away from the city where libraries and dictionaries abound, am writing it from parched, rural Buhera – my birth universe. There, dictionaries are hard to come by and, with power gone, I cannot google. But does this meta-narrative of black victim-wood not conveniently forget our own role in slavery? Our own role in the conquest and occupation of us?

The Askari was an African. Does the meta-narrative not forget our own role in the subsistence of formal colonialism for nearly a century? Throughout colonial Africa, there was the King’s African Rifles to keep colonies for Britain, was there not? Yes, forget our own complicit role in neo-colonialism that makes occupation of the continent “long durree”, to use another French phrase? A long colonialism. Were the Mobutus not sons of this continent?

My good friend Albert

Indeed forget our own role in creating knowledge systems and educated short-hands so much in vogue, used to ornately disguise the state we are in, and continue to be in, long after we have fought a war, won it, pulled down an odious foreign flag, raised a darling, decorated piece of unifying cloth – our own – then installed a president after our own colour, renamed towns and cities, ritualized our so-called Independence, and much more. “Decolonisation”; “Scientific Socialism”; “Independence”; and then – most foul of all – “Post-Independence”; “Post-Colonial”.

And much more some such shit than I care to repeat here. These grand, sonorous illusions are coins of the realm, coins of an Africa from which the coloniser has long left, in which the African has taken charge, or so we think. Creating an illusion of movement, of progress, of charge, of an escape from an enthralling colonialism. Really? Who would sharpen his/her spears when the daily song is one of accomplishment? Build new ramparts when the invader is sung as defeated, a new, African peace won?

Gird for new, higher struggles against a history and epoch called ours, one so bedecked by parlance and lexicon of complacency? A thesis of “end of history”? Of an Africa that has come, and is now truly owned by its heroic sons? It is these false notions, totalising notions, so crude against outward reality, and yet so much in vogue, hypnotically incanted in factories of ideas -schools and universities – dutifully by African sages, African interpreters, to whom we all look up, from whom pearls of “knowledge” flow to blight generations, including those yet to come.

My friend – Albert Chimedza – puts it so well, if not with a cynical jolt we sorely need. So perfected is long colonialism, so perfected are its justifying and disguising idioms, tropes and myths, that the whole system no longer need a white native commissioner for enforcement: we now do it ourselves, and with such a level of brutal efficiency as is sure to astound the whites who invented them for us, and enforced them only half as well. It is despairing; angering.

The day Wright was challenged

But Richard Wright. Back in America, a black family in the mid-1950s challenged Richard Wright to “live” his idealism on Africa by repatriating himself to Nkrumah’s Africa. Ghana had just got its Independence. Or was just about to. It only had a handful of high school graduates, still less college graduates.

And yet the whole administrative edifice which British colonialism had invented and bequeathed it, needed to be manned by literates so hard to come by. Manned knowledgeably. I am talking of a few years before 1957 – Ghana’s year of independence when the flame of Pan-Africanism burned incandescent, galvanising the tri-continent of Africa, America and the Carribea.

The likes of George Padmore had decided to “live” their Pan-Africanism by joining Nkrumah, all to make good his experiment on African independence. Similarly, Richard Wright was now being asked to test his idealism, live his Pan-African pretensions. Read his “Black Power” – a fascinating book dedicated to his mental whirlwind at the thought – the horror – of having to “live” his convictions.

And his odyssey into Nkrumah’s Ghana: then still very African, very natural, nearly pristine, for all that the British had done to it since the fall of its native rulers, among them the Asantehenes. Wright had a presentiment of doubt, of evil even, well before he boarded the ship to Ghana. Suddenly all he had read in Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” – Conrad’s Africa – began to look, nay began to menace real. The Africa of cannibals.

The Africa of dark hearts; of gratuitous brutes indulging in mindless bloodletting orgies. The Africa of witches, prowling hyenas, lions: Churchill’s vast “zoological zoo”. Yes, Africa which stripped one of all humanity, turning him into a Con-radian brute repeatedly chanting, Kill, Kill, Kill, to everything, to anything. The Africa of deadly insects that infected, killed wantonly.

Meeting Africa, Ghana

Wright plucks courage and boards the ship to the West Coast. Every day that passes does not register progress in a journey back to his roots, a day nearer his destination, origins. Rather, it becomes a menacing, tragic pull – a hurtle – towards a dreadful endgame. Finally he sees the African coast, and the air becomes oppressive, pestilential, well away from the balmy breeze of America’s civilized Atlantic.

Soon the ship drops anchor, docks, and the African shore opens its arms for a fatal embrace, reception. Naked bodies, smelly, dirty, untutored, animal-like. Humans squatting to relieve themselves in the open. Flaccid breasts that drooped, to which black urchins hung and vainly pulled for nourishment. No language: weird, animal sounds to which civilised man reads no reason, no rhyme. Goodness! He cringes from contact with the Ghana of his dreams, hesitates and is about to dash back into the safety of the ship’s haul, into the safety of the frothing ocean. A white man briskly walks past him, emitting a gay whistle, walking confidently to a destination he himself cringes and recoils from. Accra. This white man, so much at home on this un-homely continent to which Wright traces her forbears! Black? White? Black history? Black ideals? The irony! Gentle reader, Wright writes so well, so vividly, about his experiences on this, his first day in Ghana that I don’t need to spoil it for you by my poor English, my poorer expression. Get yourself a copy and, please enjoy.

What do you call it then

What I sought to demonstrate – and hopefully did – was the sharp tag between idealism and reality, between convictions and experience. More important: that colour does not matter at all. That colour is no insurance against prejudice. Contempt. And when a black becomes contemptuous of an African, what is that called? Racism? Come on!

What matters seems to be the person lurking inside, the mind beneath the garb of colour. Ghana is a great country; was already, by the time Wright visited it. So great that not even the depredations of colonialism diminished its worth, the worth of its great citizens, its great civilisation.

But all this was lost to Wright, a fellow black. All this was felt in the veins of the white colonial official who strode past him, gaily, tuneful whistle in tow. So much about being black. Race. So much about knowledge: how it fails to dislodge imparted prejudices against one’s own, one’s history, one’s people. I want to hurry past all this to a conversation Wright – by now much more settled in Nkrumah’s Ghana, a lot more at ease with it – had with a black “boy”, a full-grown up Ghanaian who ministered to his needs.

Call him his servant, a page, if Ghana was Elizabethan England. But an unusual servant: he had fought in the white man’s Great War: the First World War. He had had an opportunity of fighting alongside Americans, white Americans who had infected him with some strange ideas, most strange ambitions which Wright was about to come in contact with, in an astonishing way.

I want to be a detective, sar

One easy day, the servant accosted Wright. He needed a favour. What favour, asked Wright? Some American dollars, seventy-five, all told, replied the servant. What for, asked Wright. To read a correspondence course through an American college, came the reply.

What course? “I want to be a detective, sar,” said the Ghanaian. “What?”, asked Wright, in disbelief. “A detective, sar. Like the ones you see in the movies,” he answered with the help of an analogy. “And you want to take all of this in the form of a correspondence course from America?” “That’s right, sar, “ he said, happy that finally he had been understood.

The Ghanaian wanted dollars – American dollars. The Ghanaian had gone to a bank, which would not sell him dollars unless the colonial government cleared his application. Then he had gone to the colonial government and spoke to an Englishman. “What did he say,” asked Wright. “He said I couldn’t have dollars . . . You see, sar, the English are jealous of us. They never want us to do anything, sar.” Apparently the British official had suggested a similar course for the distraught Ghanaian. But in London.

The English won’t tell me truth, sar

“Come nearer; sit,” urged Wright. “Thank you, sar.” “From where did you get this notion of becoming a detective?” “In a magazine . . . You know, sar. One of these American magazines . . . They tell about crimes. I got it right in my room now, sar. Shall I get it for you, sar?” “No, no, that’s not necessary. Now just why do you want to become a detective?” “To catch criminals, sar.” “What criminals?”

Wrights said the Ghanaian stared at him as if he had taken leave of his senses. “The English, sar!” he exclaimed. “Sar, we Africans don’t violate the law. This is our country, sar. It’s the English who came here and fought us, took our land, our gold, and our diamonds, sar. If I could be a good detective, sar, I’d find out how they did it. I’d put them in jail, sar.”

Asked whether the official didn’t leave it open for him to take the course either in London or New York, the Ghanaian nationalist replied: “Naw, sar. They just wanted me to take the course from London, sar. But the English courses wouldn’t tell me all the truth about detective work, sar. They know better than to do that, sar. Oh, sar, you don’t know the English.”

Wright pressed a little further, wondering to whom the Ghanaian detective would give the evidence of the criminality of the English. “To all the people, sar. They don’t know the truth. And I’d send some of it to America, sar.” “Why?” “So they’d know, too, sar.” “And if they knew, what do you think they’d do?” “Then maybe they’d help us, sar. Don’t you think so, sar?” “Why don’t you try studying law?” Wright asks. “Law’s all right,” he said hesitantly. “But, sar, law’s for property. Detective work’s for catching criminals, sar. That’s what the English are, sar.”

Our United States Dollars!

Gentle reader, sar, I don’t know what you make of this conversation. Or if you make anything at all, sar. Like I said, we are in this business together, the business of seeking knowledge, and seeking it in right places. Which means also knowing where bad knowledge is got, all to avoid it. And then knowing what to do with it, once we get it. Who to give it; what to use it for. Which also means knowing what not to use it against.

As I write this piece, I am looking at a hilarious headline: “Mawarire gives birth in America”. I read on. It is Pastor Ivan Mawarire. The hashtag hero; keyboard warrior as one of my dear daughters call him and his brigade. Congratulations, Pastor. Makorokoto. Amhlope! One more citizen for Trump’s America!

What more can a father wish for, beyond a child born with an American spoon? I cast my eyes further afield. There is Advocate Mahere, sitting in Africa Unity Square, right at that point where all the lines of the Union Jack that bedeck “Africa Unity Square” meet and intersect. The navel. She is so young; she is so beautiful? Does she know her elders left the Union Jack, decorated and manicured it for her relaxation? Even indigenised it: Africa Unity Square, but without tackling the Jack?

She is being accosted, poor girl, accosted by our black policemen, all described as hungry. They want her away from the epicentre of the Union Jack. But to where? The ambiguities of Independence! It preserves Albion’s symbols; it trains a Force that ejects, liberates children from Albion. Knowledge? She does not want to be ejected. She does not want bond notes, and will go to war for it. She wants to teach ordinary citizens not to fear their Government.

Bond notes, she maintains, amount “to stealing our wealth”, our “savings”! These black tyrants! Stealing our US dollars. OUR United States dollars. She is fearless! Gokwe Nembudziya. Cde Elias Hondo. Richard Wright. The Ghanaian who wanted to be a detective. The British who must be caught. The Americans who must know. Our hope: maybe they, Americans, might help us. Our United States dollars. Icho!

Comments