EDITORIAL COMMENT: Dairy expansion success can be pushed a lot further

With dairy farmers confident they will reach the target for this year of 90 million litres of milk following the 15 percent rise in production over the first 11 months of the year, we now need to make sure this strong growth can continue with any obstacles identified well in advance.

Zimbabwe still has to import a lot of dairy products to meet even the reduced demand seen at present. Estimates vary but 130 million litres of raw milk appears to be the lowest demand estimate, and even that is only a little over half what we produced in 1990, meaning we need to boost production another 45 percent before we even start thinking about expanding the range of our dairy products and looking at ways of making them more accessible.

It is not that easy to expand anything that requires animals with long gestation periods like a cow, as both our beef and dairy farmers know.

For dairy cows there is an additional delay since the cow needs to drop a calf before becoming a milk producer. So a farmer wanting to expand their herd has to think two or three years in advance.

But our dairy farmers have been thinking like this for some years now as the they regularly breed more cows and expand output, to the extent that Minister of Finance and Economic Development Mthuli Ncube in the 2023 budget announced the process of cutting back duty-free imports of bulk raw milk powder and bulk raw cheese. He announced a formula to spread this over several years, roughly the number of years our farmers need to bring their milk output up to the minimum level of self-sufficiency.

We now probably need to start tackling two major programmes to boost the dairy herd and to ensure the final milk, yoghurt and cheese is actually affordable by more people than today.

The affordability problem, and demand for dairy products is lower than past peaks, is partly the result of having to import such a large percentage of our dairy needs, even when these are in bulk, and partly the result of the ever rising price of stock feeds, since farmers are like everyone else in business with the selling price being the cost of all inputs plus the reasonable profit margin.

For the imported share we are largely tying ourselves into the production costs in South Africa, our major source of dairy imports, and these are not necessarily the same as those in Zimbabwe.

The stock feed supply is something that our farmers need help in addressing, largely by seeing what they can grow themselves, using the bags from the stock-feed companies as a supplementary source, rather than a primary source.

There are already pilot schemes for irrigation farmers to grow and harvest high-nutrition lucerne and similar crops which can be dried and baled.

This needs to be accelerated and dairy farmers need to become involved, remembering that they have a good source of manure, since dairy cows are normally more tightly controlled in their movements than beef cattle.

The other major factor is to get more farmers involved. For those with larger farms this can follow the traditional paths, where the limiting factor is the amount of capital available to the farmer for investment, how much the farmer has and how much they can borrow.

The other path involves expanding dairy farming in the smallholder sector. We have been discussing this for decades and even trying out some schemes, mainly pilot and proving schemes. Smallholder diary is common in several European countries and some Asian countries, so it is a viable proposition.

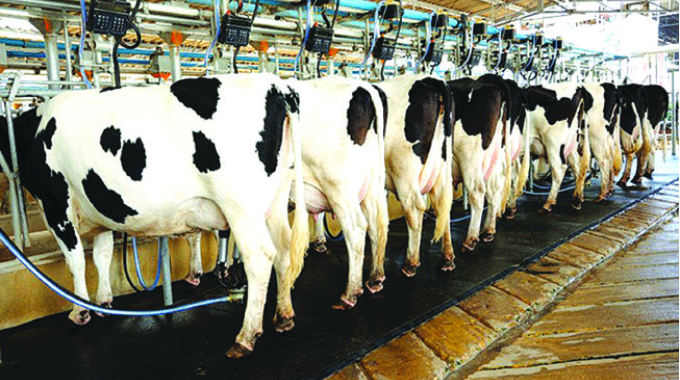

In the modern age, in a tropical country, this basically involves having a number of smallholder dairy farmers in a single community. They share some of the required infrastructure, such as the cooling tanks, which are essential, and perhaps even the modern milking barn, each bringing their herd in for milking consecutively.

Sometimes this can belong to a co-operative, but it could also belong to the company buying the milk, and other ownership models are available.

But the critical point is that enough milk comes through each day to the collection point to make it worthwhile for the buyer to send the truck. Transporting the milk of a small six-cow herd does not make economic sense until it is combined with the milk from several other herds. Basically a small-scale farmer wanting to go into dairy needs a few others with the same idea in their immediate area.

But there are also local markets. When Harare was a small town, during its first couple of decades, almost all the milk and other dairy products came from just two farms, Glen Lorne and Greendale, who unusually were both actively farmed by competent settlers and who each sent a cart down ED Mnangagwa Road and Arcturus Road early each morning with churns of fresh milk, to fill the containers brought by buyers. There were no fridges. Butter and cheese had longer shelf life.

In time the reusable glass milk bottles with a fresh foil cap came to dominate distribution for many decades, long before the single-use cardboard cartons that now are ubiquitous. It might be worthwhile working something out along these sort of lines for the small towns and new settlements springing up, supplied from farmers down the road.

Farmers, or farming communities, could also do more on-farm processing. At one stage a variety of cheeses, for example, were made across Zimbabwe on farms. A few still are if you know where the fancy boutique food shops are. The cheese competition at the annual agricultural shows were rather important, since the winners and runners up usually could expand their business on quality grounds.

Eventually these became almost meaningless since almost all processing was concentrated with the Dairy Marketing Board and the DMB won first, second and third for all types and classes of cheese with zero competition. But the return of competition could be the start of something big.

But we could return to the local varieties. France, where they take food quality and variety seriously, has around 200 recognised cheeses made from milk from cows, sheep and goats, mostly by farmers and farm communities in specific areas. The best of this production is exported everywhere, but the varieties grew up in the communities before they were commercialised.

This adds a lot of value to dairy farming, and that value in this sort of production system stays within a community rather than going to the shareholders of a factory.

So there openings, that can first bring us up to the reduced levels of self-sufficiency we need, and then which can be used to create and produce a far wider range of products. And our dairy farmers can make more money and build up their farming businesses.

Comments