Zim impressive on tackling climate chan

Jeffrey Gogo Climate Story

ZIMBABWE’s climate diplomat Veronica Gundu believes the country has made steady progress in tackling climate change in a difficult economy, as the annual UN climate talks in Morocco closed last Friday after two weeks of tense negotiations.

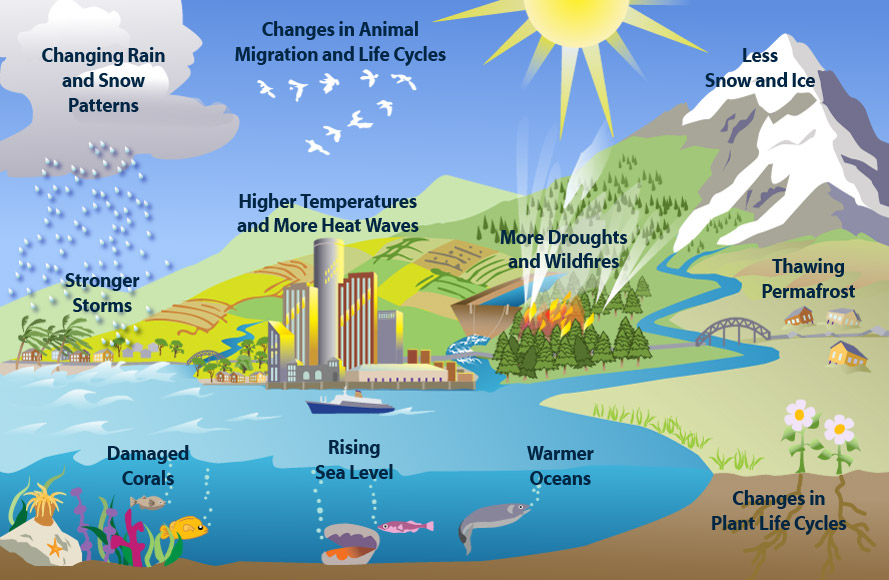

Zimbabwe has come face-to-face with the harsh realities of a changing climate. Temperatures have soared 0,7 degrees Celsius in the last 100 years; and rainfall declined 5 percent since the 1960s, on the average, while droughts and floods have become an almost everyday thing, say experts. Aided by a weak economy, climate impacts have left a trail of destruction, wrecking lives and livelihoods, and resulted in massive financial and asset losses.

One of its greatest impact has been felt in agriculture, which supports 70 percent of the 13 million population, where output of the maize staple has more than halved.

“The few climate initiatives that have been implemented by the Government, UNDP, OxFam, World Vision among other partners, have been a success and have been scaled up and this has seen transformation of livelihoods,” Mrs Gundu told The Herald Business, by email.

Mrs Gundu, who is also deputy director of climate change in the Ministry of Environment, Water and Climate, said as the science intensifies, “Government is working hard to scale up such initiatives to increase community resilience”.

She said climate change was a global challenge and a broad developmental issue closely linked with other socio-economic and environmental issues. As such, “measuring the effectiveness of our actions is a challenge as these cannot be separated from the broader developmental agenda of the country”.

Authorities have since 2008 pursued a deliberate policy towards growing not only agriculture production and food security, but also building resilience within the communal and smallholder-farmer communities.

On the average, Government has delivered roughly $25 million inputs worth to thousands of households for free each year, but even then, hunger remains a major concern, as frequent climate-linked droughts and floods wreak havoc.

But with successive cuts in public spending for the environment, water and climate sectors, these interventions have barely scrapped the surface. Since 2012, Government has cut spending in these sectors by more than 66 percent, negatively affecting work that minimises climate damage, reverse biodiversity loss, enhance water availability and others.

Further, farmers have received fertilisers and seed from Government, but not rain. Authorities just cannot make it rain. And a lack of rain has hamstrung the inputs support programme.

Private sector-driven initiatives such as the one by global charity Oxfam on irrigation supporting 300 families in Masvingo province have made some difference, but even they are facing limits.

Oxfam said in a 2014 report that its successes on the adaptation project were facing challenges. It said the drought of 2012/13 caused significant water stress for the irrigation project, but the heavy rains later in the same season damaged irrigation infrastructure, including the main pipeline. Clearly, the amount of work needed to adapt Zimbabwe’s social and economic systems to changing climates goes much deeper, from policy alignment to resource mobilisation to effective implementation — and success is not guaranteed either.

Mrs Gundu said Government was building a solid policy foundation to help Zimbabweans cope with climate change.

“The country has a National Climate Change Response Strategy crafted in 2014 and at the moment the Government is in the final stages of approving a National Climate Policy that seeks to provide an overarching framework to climate change activity implementation in Zimbabwe,” she said.

Long in the making, Mrs Gundu said the climate policy “will indicate the legislative, financial and regulatory issues needed for enhanced climate action as well as incentives required to transform our economy towards low carbon intensity”.

She is hoping that local climate action will be aided by other complementary policies in renewable energy and forestry.

Global intervention

But if domestic actions are financially or technologically inadequate, the industrialised rich world must rightfully chip in. At least this is the hope that Zimbabwe and Africa carried going into Marrakech for the so-called “Action COP” — the COP, short for the Conference of the Parties, that meet annually to map global climate strategy under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Marrakech was billed as the COP that will speed up action in the implementation of the landmark climate treaty, the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit global temperature rise at 2 degrees Celsius in this century, and deliver a minimum $100 billion per year in climate funding for poor nations beginning now and beyond.

After days of negotiating, there is no doubt the world is united against climate change, but the talks in Morocco appear to have drowned under the Trump fear.

At a time the world should have been more excited about the coming into force of the Paris Agreement in record time — three years ahead of schedule, precisely — the threat by incoming US president Donald Trump to withdraw his country — accounting for a sixth of the global emissions total — from the accord seemed to over-shadow the talks.

Unsettled negotiators spent time working out the permutations of a US exit, with reports and counter reports on the issue widely circulated, sources who attended the meeting say.

Talks did proceed fairly smoothly, they say, but could have been better without the US issue hanging over them. It should come as no surprise, however, that Mr Trump may jettison the climate treaty. Successive US administrations since Bill Clinton have acted in similar manner.

Mr Clinton pressured the world to limit ambitions to cut greenhouse gas emissions under the Kyoto Protocol to just 5 percent from 20 percent compared to 1990 levels.

George W. Bush then withdrew the US from the Kyoto Protocol completely. Barack Obama maintained this status quo before his administration began to arm-twist everyone else into accepting lower ambitions beginning with the disastrous Copenhagen COP of 2009.

Later, Mr Obama had appeared to relax, promising to cut emissions by between 25 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, but scientists warned of the inadequacy of the US’ actions, particularly at a time when deeper cuts were needed to meet the 2 degrees Celsius goal.

In Morocco, the US should have never been allowed to create an atmosphere of uncertainty of the future of the Paris Agreement. Zimbabwe, and the rest of Africa, are still hoping to get a share of the money promised by rich countries, the ones historically responsible for fuelling global warming and climate change, to help their people cope with the science’s dangerous impacts.

E-mail:[email protected]

Comments