Zimbabwe: Names from the forgotten war

It was at bush training bases that war language was developed to motivate the guerilla fighters as well as give them a better understanding of what they were fighting for

The Other Side Nathaniel Manheru

IT has been a good 34 years since our war of liberation ended in victory. There is a whole generation that grew after the war, a whole generation for whom that war is but a series of gripping anecdotes. Or even narratives of critical claims and falsehoods by those against whom the war was launched and fought. I recently dealt with one such impressionable born-free who thought his people’s history can be written or retold by Rhodesians and their kith abroad.

He had just discovered one Meredith, celebrating this as a discovery rarer than a mother’s virginity. So it is incumbent upon those of us who witnessed the war, more so upon those who fought that war, to share memories of that brutal war that created a beautiful country, a beautiful people, a lovely nation. I just want to deal with one small aspect of that war, all to show that the war and its rich tradition is a veritable resource for defending our revolution, our cause, our quest as a people.

When no two wars are ever the same

Wars do create their own language, their own vocabulary, by which occurrences within, and because of them, are described and become describable. I suppose it is in the nature of all wars to do so, given that no two wars are ever the same, or comparable. Each war produces its own lexicon and lexicography, yes, its own grammar and narrative. Wars are fought differently, in unique spatial and cultural settings, mobilising different people, using different weaponry, employing different tactics for different ends.

Each war spews its own atrocities, moulds its own humanity. The beast in man outs; the tenderness of life tenuously holds, always seeking to restrain and humanises that monster unhinged. Each war invents its villains; paints its heroes. Of course the narrative always belongs to the victors, who need not be winners on the battlefield. Check our own war. The only thing that all wars do, and do without fail, is to create victims. But all this is another matter, another story, for another day. I am not chasing that today.

Texture of great deeds, statements

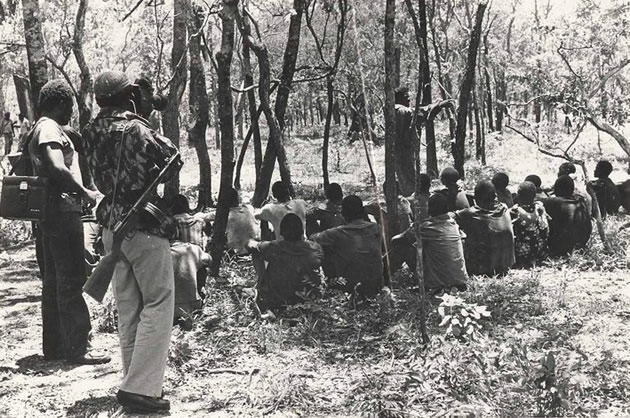

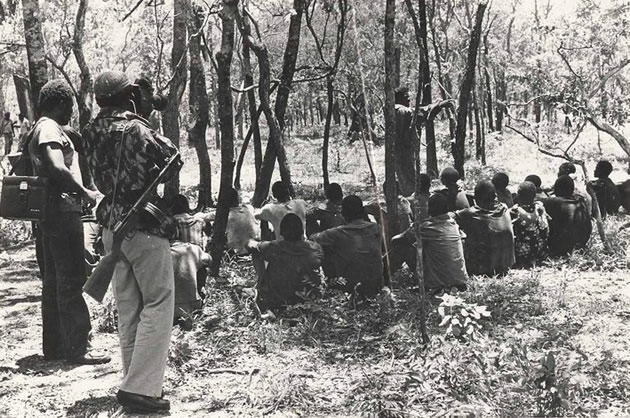

One key production of our war of liberation was a rich vocabulary that developed around apparatuses of that war, principally the gun that makes all wars. The forces of liberation started with very modest guns. Perepeshas, they were called. Ranged against the Rhodesian firepower, part of it mounted, airborne, that phase of the struggle demonstrated sheer willpower and bravery, even in the face of a ready, certain death. I call it the age of sacrifice, of example.

Rhodesian historiography calls this foolhardiness, forgetting out of those acts of determined desperation would emerge the Chinhoyi Seven we celebrate today. The real story was not the elementary gun; the real story was the brave heart behind it. The deep cause that motivated such acts of bravery. After all it had happened before, back in history. Then it was the maxim gun against home-made guns, spears and even stones and fists.

After all it would happen again. That is why the image of the shot child in arms of an outraged student is what today symbolises the day of the child. The outrage was Soweto, the setting apartheid South Africa. Great deeds, great statements, come from simple acts ranged against formidable power armed with its awesome instruments. That, probably is what Marx meant when he said history is made by ordinary people, never by princes of power. Those only seek to delay it.

Renaming the AK

With time, light-to-heavy weaponry came into play, came the way of force of liberation. Mortars of various sizes, rocket launchers, all to reinforce the basic weapon: AK47. Interestingly, this Russian-designed gun was rarely called by its trade name in that war. It was called, fondly called “Sabhu”, as if it was some kind pet meekly and languidly dozing beneath one’s half-clad, drooping thighs. And there was a tuneful song sung to its glory: “Ndiani anoenda Muzambique/Kunotora Sabhu yangu/ Nhamba yacho four, double nine, six Muzambiki”.

It was an elegy to a deadly gun, but rendered with such bursting animation that one thought it was a prayer to a benign god. Or even to a routine heritage to a grateful receiver, numbered to ensure it reached the intended scion. And the number of the weapon would blend with the melody, would drop down our lips as if we were rehearsing a good, kindly brother’s room number somewhere in Old Highfields in those Rhodesian days.

Death had lost its ugliness, its tragic turn, tamed by war’s all-encompassing lyrics. From 1977 when the war came to our area, until well into independence, I never knew or called a “mortar 82” by its real name. It was a “morotero”! And you did not have to know it, even to see it. Here was one weapon whose terribleness was sounded by its name. A weapon whose hospitality lay in that it armed those who fought for us. There was a cold hiss of death to it; a possessive, melodious friendliness to it. But it had been tamed, made ours phonetically, alongside the fact that it was clutched by a hand of one of us.

Singing death in war

But the war also domesticated names of exotic weaponry, in the process making the deadly weapons household articles in the home of a struggling people. The war re-familiarised exotic weaponry, deadly weaponry. For me this was the genius of the whole war, the genius of its core, diverse communication acts.

That genius turned an unfamiliar, even sinister instrument of death, into a familiar, even likable article made pliant through verbal stroking, through domesticated re-naming. Professor Pfukwa will relate to this. That same mortar 82 was renamed “duri raambuya Nehanda”, or grandma’ Nehanda’s pounding mortar. Except the pestle was a deadly stubby, prickly rotund projectile which once launched, hissed its deadly message home. Cde Chinx sort of captured it in a line in one of his songs: “Ruzhinji rwaitambudzwa zvikurukuru nemuvengi”.

In that song, the struggle is described as a flying projectiles that hisses the song of freedom. It is a deadly understatement in song. Similarly another gun, an LMG (light machine gun) with its pot-like magazine, was renamed “poto yambuya Nehanda”, grandma’ Nehanda’s pot. The renaming of these guns recalled our history and its heroic personages, while gaining our confidence in these articles of death. When you consider that Ian Smith’s propaganda was to make war veterans look like mindless terrorists who slaughtered wantonly, this was a veritable mobilisation breakthrough for the guerrilla.

He and his mortal war paraphernalia had become a household name, literally. The landmine was renamed “chimbambaira”, the potato, which was a working euphemism for a deadly tool of death and destruction. They give this a different name in Iraq and in Afghanistan. Of course “bazooka” remained “bazooka”, its name having been deemed terrible enough to awe the foe, to project a sense of formidableness to friend. It kept its name, keeps it to this day. The Rhodesians did not help matters by putting bounty on each of these weapons.

That action reinforced the bonding between a fighting people and their standing army, its weaponry.

Renaming Rhodesian arsenal

Of course all wars have two antagonistic sides. The same war genius also named and renamed the Rhodesian weaponry. Derogatorily, all to rob the Rhodesian arsenal of its awe. To damn it. You could not have been praising the very gun that was trained against you, trained against your cause, without building a psychosis of fear, impotence and defeat.

Interestingly not a single Rhodesian gun got a vernacular name, or was ever romanced the way weaponry from the East was. Quite the contrary, they all retained their foreign names, in keeping with their desecrable significance as instruments for propping an invading, foreign force. It was not a weaponry that liberated, but one that enslaved. Two weapons stood out from the Rhodesian arsenal.

One was known as “nato”, itself Rhodesia’s answer to the LMG, or “poto yambuya Nehanda”. It leaned on a tripod, something that gave it a crouching stance which raised its sights like a rock gecko, that one with a rough, warted top, a bluish underbelly, and which behaves like it will smash its head on hard rock, maybe in a fake show of strength. So during those war days, “nato”did not refer to a military alliance; it referred to an alien gun that killed “our people”, donated to Ian Smith by his western kith and kin, collectively grouped as NATO.

The name of the gun summarised the alliance against our cause, our freedom. It summarized the Rhodesian cause. No Zimbabwean who supported the war can ever get reconciled to NATO, whatever its re-imaging efforts. The other gun was called a “Bren gun”, and war legend had it that it had come from some faraway country called “West Germany”.

This gave a remarkable contrast, given that East Germany — West Germany’s antithesis — was equipping comrades.Those two bad guns gave Rhodesia its war face, a reviled one at that.

Of course the Rhodesian workhorse gun was an FN, which remained denoted by those two alphabetic sounds. To this day, that gun carriers its Rhodesian aspersions, whoever might be carrying it today. That is how powerful war communication and naming was, is. It lasted. It lasts.

One A-least Sparks

The American government is not too pleased that Zimbabwe has turned East. It is riled that Zimbabwe is now attracting investments from China and Russia, especially Russia. Those of us who covered Russian foreign minister Lavlov when he came, would have picked a seemingly innocuous detail in his Darwendale commissioning speech.

He acknowledged Chinese investments already in the country, or set to follow. That short reference was meant to demonstrate that Russian and Chinese capital would not fight for turf in Zimbabwe.

It would coexist; it would complement.

This is the detail which some emptily celebrated white liberal South African retired journalist — one Allister Sparks — missed.

Writing in one of the South African publications, Sparks speculates that Mugabe turned to Russia to spitefully hit back at the Chinese whom he claims had virtually snubbed Mugabe during the recent State visit by setting impossible preconditions for financial support for Zimbabwe.

For all his vaunted years of experience, Sparks does seem very poorly equipped to deal with, and interpret, an emerging world realignment phenomenon, post Ukraine.

Give us more time!

The Americans are using all sorts of dirty tricks in the hope of intimidating Zimbabwe, in the hope of scuttling Chinese and Russian investments here.

One of my readers transposed his own fear and impotence, transposed it to his country, Zimbabwe.

He use the animal imagery I used in my instalment last week, to suggest Zimbabwe is a hapless victim of America. He thinks her defiant stance against a superpower only invites greater retribution, greater misery. He is entitled to his view, cowardly though it is. But we must understand current politics in the ever emerging world order. I thought the Russian Foreign Minister made another telling point, this time away from scribes.

He recalled his recent encounter with America’s Kerry, during which encounter Lavlov cynically asked Kerry if America was in the habit of reviewing results of its peace-making efforts.

Could he, added Lavlov, address that question paying particular regard to Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, Syria and again Iraq! Kerry could only say, give us more time, give us more time.

Daring America

At this existential moment, America badly needs a success case for show. None exists presently, with all its operations going up in smoke, daily.

The emerging situations, all of them of America’s creation, are posing real threats to America’s world dominance, real or imagined.

Much worse, poking fun and ridicule to all her pacification efforts. In the case of Middle East, a new generation of fighters, diligent fighters, are emerging who have grown up and have been made stronger in a habitat defined by American air fire power.

Not quite a winnable war when your raining bombs appear to nourish those they are supposed to stun and demolish. Nourish their cause even, placing them up as the only real defenders of the Faith. Those bombs are best recruiting message for ISIS.

And once inured to that harsh habitat, once habituated to aerial war, the blossoming fighters now dare America to send boots on the ground. America is no longer than awesome power.

America will not sent boots on the ground, fearing greater mortality in an election year. We know what adjective to give such reluctance: cowardice.

America’s lonely war

And what a remarkable contrast with Putin. He has been given East Ukrainian rebels who are fighting the government there for adoption.

He has embraced them. Whatever setbacks they may suffer, he never lets them down, even occasionally sending Russian boots, tanks and food into the fray. Contrast that with the Kurds desperately battling to keep encircled cities in Syria and Iraq, closer to the border with Turkey.

And the message is clear: America’s hard armour has been tested and has been found to be useless. And hard power is a tool of last instance. What next? America might have to fight that war against ISIS eventually, reluctantly.

Not for the sake of Syria, Iraq or Israel. Or Turkey, or for the Kurds. But for the sake of its standing as a superpower at a time when Putin is busy pecking America’s awesome horns, via proxies of course.

So far the bear’s bite has sunk into plumes of feathery horns. Could there be enamel beneath, goring enamel?

I was at the recent UN. I saw Obama try his damnedest to convince the world ISIS was a threat to world peace.

Was everyone’s enemy. They slit throats, he roared in learned outrage.

They are animals, he added. Until someone told him that same month Saudi Arabia had slit more throats than ISIS, Saudi Arabia which is Obama’s bombing ally against ISIS. He cut a frantic, pitiable figure whose tale was more tired than that told by an idiot.

In the case of Mugabe’s speech, no mention was made of ISIS, whether in support or condemnation. This is America’s war. Let her fight and lose it.

Pee on sacred wings

The essence of American global dominance has always been hard armour, one held both in check and threat, always led by soft power by way of its all-edifying values, all-developing dollar, and those many food gifts donated in the name of “American people”.

Today that armour has failed, in fact failed that day when Serb women danced and peed atop wings of a downed stealth fighter bomber in Yugoslavia.

Later, when their bladders were well emptied, wings of the bomber drenched by their acrid discharge, the Serb women scribbled: we thought a stealth bomber was invisible? From that day, America lost the war, lost its status as the sole superpower. In this new war against ISIS, it has unfurled another bomber, but to no effect on the battlefront.

Lessons from the graveyard

Much worse when America slapped us with unjust and unjustifiable sanctions. We met its vindictive side, against a very small, yet supremely proud people. What had we done to anger mighty America? Where resided our power to pose “a continuing, extraordinary threat” to her might? Something rang puny and spiteful, themselves never attributes of a civilising power America thinks it is.

When we recall how in the early seventies it chose chrome for our freedom, we condemn it utterly as a racist country.

When we recall that “nato” gun which the Rhodesian gunner carried and triggered against us, we see blood on its civilising mission, wondering what lessons do the dead derive from graveyards.

But we also see how history moves slowly, often cyclically, often repeatedly throwing up choices we have met before: is it the “Sabhu” or the Bren gun? Why is the choice ever the same as yesterday?

Does history not move forward, suggesting new dilemmas for an evolving people? Demanding new sacrifices from a suffering people. Maybe it doesn’t.

Which is why the liberation war, its naming tradition included, remains a key resource with which to fight current battles.

Icho!

Comments