Intellectual political responsibility

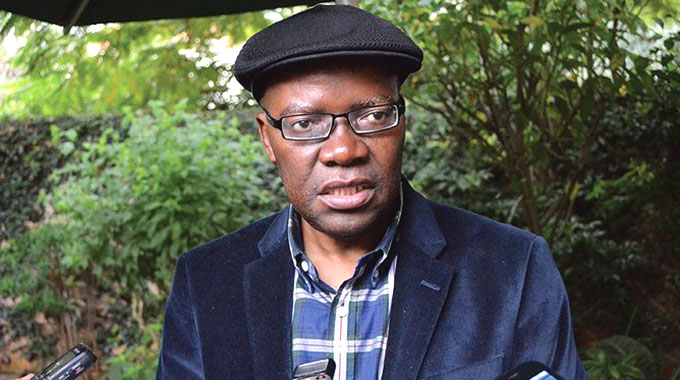

Reason Wafawarova

IT is critical that intellectuals are called upon to accept or face political responsibility; especially those that choose the public platform to play custodians of the collective opinion of everyone else.The question of how intellectuals should relate or react to the values and demands of influential power centres is a pertinent one — more so when it comes to the influence of political players on such institutions as the media and academia.

When the media and academia begin to obsequiously sing praise political personalities, the threat to the integrity of these institutions becomes worrisome.

Responsibility has two axiological aspects to it. It calls for an admission of accountability and also comes with a claim to authority — itself an expression of power. Like with all forms of power, irresponsible behaviour can have disastrous effects.

The media often treats intellectuals as specialist advisors, and that role is so cherished by fame-hungry intellectuals hankering for easy public attention, but it also carries with it immense responsibilities that have to be complied with.

To those who consider themselves outsiders to the arena of intellectuals, every intellectual carries around them an aura of power, and it really matters little that the intellectual in question might be a failed one.

It is synonymous with the age-long belief that whatever is printed in a newspaper is meritorious by definition.

Those intellectuals hired as political advisors to powerful political figures often mistake the power of their masters for their own, claiming credit for every achievement attributable to those they advise, and rashly disowning every act of error as the fault of the unheeding politician.

When Morgan Tsvangirai’s political star was shining a few intellectuals lined up masquerading as his kingmaker advisors.

Now that the man is irreversibly heading for the doldrums we are told it is his entire fault, and those whom he hired as his intellectual henchmen have zero appetite to stand by the disgraceful ideas of a man smarting from an enormous election routing.

The pretensions to power on the part of intellectuals can reach catastrophic levels. It must be unambiguously understood that an intellectual opportunity to speak on matters of the proletariat does not make the intellectual an expert proletariat. It is simply an opportunity to speak, to persuade, and to influence.

It can never be elevated to a substantive right to determine the affairs of the proletariat.

For all its nobility and intellectual integrity, Ian Scoones’ study of Zimbabwean resettled farmers was merely an opportunity to express an intellectually informed view, not a transformation process making the researcher an expert resettled farmer, and certainly Professor Scoones cannot be faulted on any of this. It is because he is a respected intellectual with a strict adherence to intellectual responsibility.

There are no other specialist indigenous Zimbabwean farmers except those carrying out the farming, and to this extent Tendai Biti’s intellectual demonisation of the resettled farmer does not constitute failure of the land reform programme, regardless of the number of times Biti calls the programme “chaotic”.

This is the converse of Professor Scoones’ illustrious work. It is the height of intellectual irresponsibility, if we loosely elevate Biti’s writings to matters of intellectualism.

Now Zimbabweans must be very clear that politicians organising protest action are not protest experts in themselves, and neither are the intellectuals expressing their complex views about protest mass action in velvety superlatives.

This is why the organising of a protest like Zimbabwe’s 1997-8 food riots did not exactly mean that the organisers knew what to do next.

Those who rode on the wave of the protest vote in the Zimbabwe 2008 election did not know exactly what to do in the 2013 election, apart from making public wishes that the voter would once again protest. Indeed the voter protested, only this time against the former beneficiary of the earlier protest vote.

Morgan Tsvangirai calls this a “huge farce” and he is convinced it is “massive electoral fraud.”

The 2013 election result speaks loudly against every assumption from the neo-liberal Western-backed politicians, even as endorsed by their legion of intellectual analysts.

In the aftermath of the announcement of the election result, Tendai Biti publicly admitted that him and his colleagues were so shocked that they were “walking like zombies.”

Having said that, it is important to mention that there were a few intellectuals who made next to accurate predictions on the election outcome, notably opinion poll consultants hired by Freedom House and Afro-Barometer.

These seemed to adhere to intellectual responsibility even in circumstances where established facts ran contrary to preferred outcomes.

One spectacular pretension of intellectuals is the lofty assumption that the intellectual community occupies a superior realm that makes it natural for the learned to undertake objective and well-informed decision making on behalf of all others.

We are told that the intellectual’s way of thinking is an offer of the key to all our problems, and endlessly these intellectual are lined up and paraded on television screens so they outline to us lesser people where the solutions to our problems lie.

Of course we have a hard-hitting reality that proves that the fruit of the intellectual’s way of thinking precisely constitutes the biggest problems of humanity — from the murderous nuclear weapons to the disastrous global warming phenomenon, nor forgetting manufacturing of public consent by a pliant media.

One of the biggest challenges to the rising Zimbabwean resettled farmer is the intellectual blinkered take on the land reform programme — the astigmatic opinion of Tendai Biti, a man who as Finance Minister vowed never ever to support the resettled farmer.

Now ousted by a ruthless ballot, Tendai Biti’s spends most of his time spiting the resettled farmer through callow opinion pieces, sometimes littered with atrocious grammatical shortcomings.

We have this intellectual criticism that almost overwhelmed the land reform programme when it was launched, the kind that Thabo Mbeki now scoffs in hindsight.

It was unrelenting criticism that left President Mugabe virtually with no friends in his own neighbourhood — all because even his regional liberation comrades believed in the intellectual opinion that said you cannot take away land from “skilled white commercial farmers” and give it to “unskilled black farmers.”

Most intellectuals are more concerned about the standards and values inherent in their professional work than they are concerned with wider responsibilities, especially political responsibility.

It is this position that makes it somewhat sensible for an African intellectual to advocate for the perpetuation of colonial hegemony — all in the name of high-sounding economic logic, as derived from the colonial legacy itself.

The values of intellectual professionalism must be guided by responsibility on the part of the intellectual, not the other way round. But who is the intellectual?

Alan Montefiore gives a loose definition of an intellectual and it appears many people are comfortable adopting this unrestricted approach.

He describes an intellectual as “anyone who takes a committed interest in the validity and truth of ideas for their own sake . . .”

He adds, “ . . . everyone must be considered, to some extend at least, to have something of the intellectual in them.”

This loose sense of intellectualism can be summarily dismissed as innocent eccentricism, but its disastrous consequences cannot be ignored in a country like Zimbabwe where everyone and anyone with the tiniest of a brain seems to have elevated themselves to complex political intellectualism in the aftermath of the watershed 2013 election.

From the look of things in the media, this is more a result of the landslide defeat on the part of the MDC-T and less for the landslide victory on the part of the revolutionary pro-people Zanu-PF.

In the name of intellectualism Rodwell Makombe accuses those that endorsed the 2013 Zimbabwean election result of “neglecting the fundamental question of the destiny of the country.”

He further lambasts those who disagree with Morgan Tsvangirai’s mendacious vote-rigging allegations, accusing them of “abdicating responsibility.”

Another loose intellectual by the name Mthulisi Mathuthu had the temerity to accuse Zimbabwean voters of “national idiocy.”

In his view this is the only way to describe a nation that gives Robert Mugabe an election victory.

But an intellectual must not and is not an angry citizen armed with a pen; striving hard to vent anger and frustration through the publicising of opinion pieces.

Rather an intellectual is one who has chosen a certain life: one that involves a commitment to certain values and one who is ready to defend such values should they ever come under threat.

A writer who defends his political affiliations ahead of intellectual integrity is not worth the name.

The need to defend the truth and moral honesty is a powerful appeal falling on everyone, intellectual or non-intellectual. However, intellectual responsibility is a higher demand on those that take it upon themselves to be the custodians of the collective opinion of all others.

Everyone has a responsibility for truthfulness, and this includes election losers smitten by the demon of denial. Abandoning truthfulness is abandoning the realm of human discourse and such behaviour is unbecoming of an aspirant leader, particularly one who dreams of being a statesman one day.

Is it an intellectual argument when a socialist is accused of hypocrisy for educating his children at a private school, or when an anti-imperialist writer is accused of rank inconsistency for residing in a country with imperialistic tendencies?

From a moral or political viewpoint, there is no inconsistency in acting in a way which is only possible if certain conditions continue, for as long as that person is not prepared to commit themselves to the continuance of these conditions.

There is no inconsistency when an anti-imperialist works and resides in an imperialist country, for the simple reason that while the residing and working are only possible under conditions created by an imperialistic system, the anti-imperialist stands opposed to the continuance of this system.

So President Mugabe stands accused of hypocrisy for calling on the West to stop meddling in the affairs of Zimbabwe while at the same time calling on the West to lift the ruinous sanctions illegally imposed on Zimbabwe more than a decade ago.

The thinking here is that you cannot tell the West to leave Zimbabwe alone and then complain of economic sanctions from the West in the same breath.

It is not trade relations with the West that must be discontinued. What must be discontinued is an unjust system that promotes economic sanctions as a tool to enforce the ill intentions of imperialism on weaker nations.

So President Mugabe is prepared to have trade relations with the West, but he is not prepared to commit himself to the continuance of a Western foreign policy of bullying and policing everyone else on the planet.

He is committed to stopping imperial hegemony and that must not be read as a commitment to disengage with Westerners.

There is no inconsistency in that, and African intellectuals must be at the forefront of expressing these views.

Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in Sydney, Australia

Comments