Inflation falls to three-year lowest

Herald Reporter

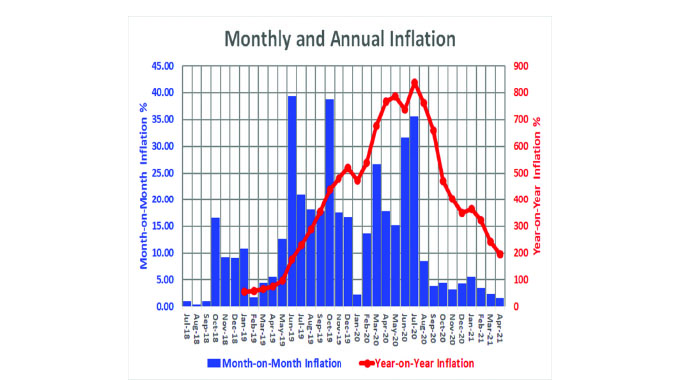

Zimbabwe’s monthly inflation rate fell to 1,58 percent in April, its lowest since September 2018, and for the eighth month in a row the country saw monthly rises in the cost of living of less than 5,5 percent, reflecting the stability achieved in August in the exchange rate for priority imports, along with general full allotment for bids for such imports.

Annualised, that is assuming that mean monthly inflation remains the same for 12 months, the 1,58 monthly inflation would translate to an annual rate of 20,7 percent. But from September last year monthly rates have been tending to fall, with an upwards blip in December and January caused partly, it is assumed, by some producers and retailers trying to mop up annual bonuses, but there were other inputs.

But even with that blip, the mean monthly inflation rate for the eight months from September has been 3,54 percent and the figures for the last three months have all been below that mean, coming down from the January high of 5,43 percent to 3,45 percent in February, 2,26 percent in March and now 1,58 percent in April.

ZimStat, the national statistics agency, does its monthly surveys of the costs of all items in the shopping basket it uses to calculate the cost of living towards the middle of each month. So that record jump in January since the auction rate stabilised would include the pre-Christmas and Christmas period.

However, even with the blip, that mean of 3,54 percent a month translates into an annual rate of 51,81 percent, high but far lower than we have seen for some time.

Since a fair number of “independent” estimates of Zimbabwe annual rate are predicting around 50 percent this year, it seems that many of these estimates are based on that eight-month post-auction average without factoring in the general monthly falls in the last quarter.

Government and the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, which look more at fundamentals than historical data, and take trends into account rather than just slapping averages into an equation, see far lower figures coming up with single figures a distinct possibility. For example, the record food harvests now being gathered, and with farmers being paid at market rates, and not being cheated, will tend to keep many basic food prices stable for the next year.

The actual annual rate, which includes the last three months of exceptionally high inflation plus the transitional August figure, has fallen to 194,7 percent, its lowest for almost two years, from 240,6 percent in March, 321,6 percent in February and 362,6 percent in January. It reached its modern peak at 837,5 percent in July last year after a year of rising large monthly price rises.

This inclusion of old data from a time when there was a rapidly rising gap between official rates and black-market rates, with most industries having to procure currency on the black market even for priority imports, means that the annual rate only tells us how much the cost of living has risen in the last 12 months.

With the discontinuity brought about by the price stability since the auction, annual rates at present are not giving much help in telling what has happened within that 12 months, such as the sudden and very sharp drop in monthly rates from September. For that monthly rates are more useful.

However, annual rates will continue to plummet for the next four months as chunks of old data are removed from the equations and then rather suddenly the historical data will produce annual inflation rates of under 50 percent.

Inflation actually measures changes in the cost of living of the average lower-income urban family, say a family living in Highfield in Harare. ZimStat assembled, through household surveys, a basket of goods and services of what a good statistical sample of such families actually buy or pay for each month. This basket includes many scores of items, some having a major effect on the cost of living and some less.

Each item is grouped and weighted. At present, the four main blocks of items in the consumer price index are: food and non-alcoholic beverages, which make up 31.3 percent of total spending; housing and utilities (27.6 percent); transport (8.4 percent) and miscellaneous goods and services (6.5 percent). The smaller block of items are: household contents, equipment and maintenance (5.3 percent); alcoholic beverages and tobacco (4.9 percent); clothing and footwear (4.3 percent) and education (4.3 percent). A catch-all of the remaining 7,5 percent would include communication, recreation and culture, health and restaurants and hotels.

This means that a modest rise in average food prices can have quite a big effect, and even a significant jump in bus fares can add a few percentage points to monthly inflation, as it did when Zupco went through a run of fare doublings. Yet a largish jump in the price of shoes might have a far smaller effect on the general cost of living, simply because people do not buy shoes every month. But for the family having to buy new shoes for all children for school, there would obviously be a big jump one month, but the statisticians even that out over a year.

This average family does, when you look at its shopping basket, live fairly simply, tending for example to buy a cup of sugar beans and a couple of tomatoes when it wants baked beans rather than squandering money on a tin. Even that 7,5 percent in the catch-all of other items will tend to be spent on airtime and the odd clinic fee, rather than on a family holiday in a hotel.

People who are better off will have, again on average, a different distribution of spending and include more items. While the bigger and fancier house might keep spending on housing at 27,6 percent of income, the percentage spent on food, the biggest item in a lower-income budget, will be a lot lower. A CEO might earn 20 times as much as a tea-maker, but is unlikely to spend even five times as much on food, even with imported luxuries.

Generally the poorer a family the bigger the percentage of its income goes on food, which is reflected in the ZimStat basket for the cost of living statistics.

This is one reason why the exchange rate stability from the foreign currency auctions had such a dramatic effect on the monthly inflation figures, since very little in that lower-income basket is now funded from the black market. It also explains why jumps in some items, such as Mercedes Benz spare parts, might not cause a murmur on the monthly rate, since they are not in the basket, yet an equivalent Zupco fare rise might cause a distinct blip.

Comments