Housing policies in Zimbabwe: An exposé of the journey

Pardon Gotora Urban Scape

Part 2

As the anxiety of the forthcoming 40th Independence celebrations slated for the City of Kings and Queens grips in, it is only imperative to flash back and reflect on the trajectory traversed by housing policies from pre-independence to date.

As I alluded to in the recent past edition of the “Three Series” dossier on the Housing Policies in Zimbabwe, the exposé commenced with a snippet of the pre-colonial period through to the period around 1907 when the first African township was established.

This episode dwells on the housing policies, legislations and programmes for the period from the around the 1920s through to 1979.

In the previous edition, I discussed about how the labour shortage in the white men’s economic endeavours prompted the recruitment of more African labourers and the inevitable increase in demand for housing.

As the demand for cheap labour expanded due to the momentum gathered at the time, so did the growth of African townships.

However, as more and more land was alienated for the establishment of the periphery of the town.

More blacks were not coerced off the land into the labour market.

Some traditional leaders were manipulated along the way, and those who defied the system were replaced with more “compliant chiefs”.

So, the traditional leaders’ land governance/administration role was now under duress and appeared ceremonial as they could no longer make their own decisions regarding settlements.

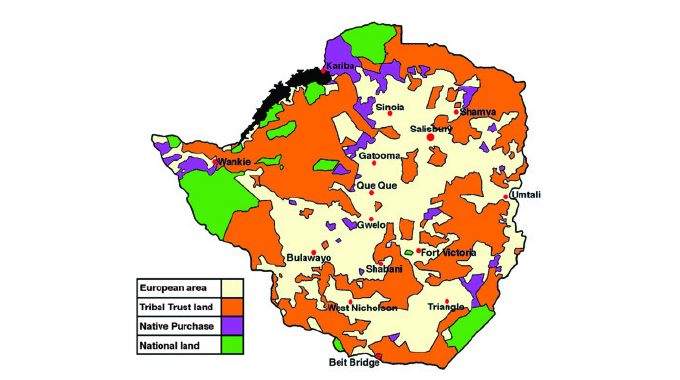

The final nail for traditional leaders’ role in human settlements came in 1930, with the promulgation of the Land Apportionment Act.

The black African land or property rights decimated.

All the land rights were now the preserve of the whites who created the Reserves (the Tribal Trust Lands) from which we draw the name “Kuruzevha”.

Black Africans were barred from land ownership outside these reserves.

This is how the colonial government tackled the rural housing aspect, albeit the reserves were mainly characterised by poor sand soils and unreliable rainfall patterns, and in some cases like the Gwai and Shangani Reserves, they were tsetse-infested.

In order to raise government revenue, these blacks were levied hut tax since 1894, which actually triggered the first Chimurenga.

Presumably the name of the tax was derived from the fact that the owner-built houses were predominantly round huts.

This, thus, meant that there was no free housing, both in urban and rural areas.

Having been deprived of their livelihoods, and the realisation of the opportunities posed by the towns, the blacks began to flock to towns, particularly from the 1930s through to 1950s and 60s as they began to feel the pinch of being forced to settle in poor soils.

However, the migration was not presented on a silver platter. The Native Passes Act of 1937 became another albatross on their necks.

There was mandatory registration of any new entrant into town at the Native Office.

Remember, at the time the District Administrators were known as District Native Commissioners while the Provincial Administrators were known as the Provincial Native Commissioners.

The term native was not used in its literary sense, but was denigratory and referred to blacks.

So, you needed to have a pass to enter or live in town, and you would always carry identification documentation or risk persecution.

Rights to be permanent urban residents were restricted in the same manner movement was restricted. It was also the same period that witnessed intensive consolidation of a range of policies and legislations governing urban development.

The Acts that made it compulsory for people to live in areas designated for the exclusive use and racial grouping classified as white, Indian, coloured and black.

The local authorities tried to address the surge in demand for housing through construction of hostels, like in Mbare, Makokoba and Sakubva to mention but a few.

However, these were not enough.

Hence the adoption of more African townships which were now called “locations” or commuter townships, from which we draw the term “kurokesheni” or ghetto.

Your Highfield, Kambuzuma, Mpopoma, Rimuka, Chinotimba and Mucheke come to mind. Some of these locations, like Highfields, bred the crop of our nationalists who later brought this independence we will be celebrating in April.

The locations were mainly created to provide labour to industries, despite the distances involved.

In order to circumvent the transport woes, the United Passenger Company was introduced, and there was a major bus stop in all the major industrial hubs with dedicated buses like for Southerton, Msasa and Workington. T

These locations were cited within easy distance of the town and with roads connected to same, but preferably running through the industrial areas.

Access to housing finance was a prerogative of the whites. The Building Societies Act (24:02), promulgated in July 1965, exclusively provided for mortgage finance for the whites.

Blacks were regarded as migrant workers, whose permanent homes were in the reserves and would return to the village.

Therefore, there was no home ownership for the blacks. They had no title to the land, hence could virtually not produce any collateral security to access mortgage finance from building societies.

Funding for housing development mainly came from rental income collected from locations.

The costs of development were passed to the township residents by way of rent increases.

This was augment by income from beer sales in these locations.

That explains the establishment of Rufaro Marketing by the City of Salisbury and the municipal beer halls (bhawa rekanzuru) in all the locations or African townships.

The bar was a trademark in the locations, and you did not find same in Borrowdale, Chisipiti or Belgravia where the whites lived. The local authority had the monopoly to brew and distribute the traditional beer (Chibuku in Harare,/Ingwebu in Bulawayo).

Informal traditional beer brewing was criminalised and heavily policed. But because of the traditional norms of beer brewing by Africans, commonly in rural areas, the practice perpetuated and was concealed. Shebeens emerged, which clandestinely brew and distributed beer.

In 1980, the independence came, and in the next edition(s) I will gravitate on the post-independence housing policies, which might also require two episodes, judging from the feedback received so far.

Feedback: [email protected]

Comments