Europe’s middle class shrinking

MADRID. — Raquel Navarro downed an early-morning coffee, kissed her husband goodbye and hurried from her family’s spacious brick home in a suburb north of the Spanish capital.

The successful events business she had owned for a decade slowly crumbled when Europe’s financial crisis hit. Now, after dropping her two young children at school, she boarded the subway to her desperately needed job as a secretary, working for just above minimum wage.

Moments later, her husband, José Enrique Alvarez, walked out the door to a charcuterie where he is a self-employed butcher. The 56-year-old was once the human resources director of a Spanish plant nursery that downsized, laying off him and half the company’s 300 workers in 12 months.

After decades of living comfortably in Spain’s upper middle class, the middle-aged couple are struggling with their decline.

Spain’s economy, like the rest of Europe’s, is growing faster than before the 2008 financial crisis and creating jobs. But the work they could find pays a fraction of the combined 80 000-euro annual income they once earned.

By summer, they figure they will no longer be able to pay their mortgage.

“We’re people who had worked our way up, and now we’re tumbling down,” Mrs Navarro said, as tears sprang to her eyes. “The economy seems to be improving, but we’re not benefiting.”

It is a precarious situation felt by millions of Europeans.

Since the recession of the late 2000s, the middle class has shrunk in over two-thirds of the European Union, echoing a similar decline in the United States and reversing two decades of expansion.

While middle-class households are more prevalent in Europe than in the United States — around 60 percent, compared with just over 50 percent in America — they face unprecedented levels of vulnerability.

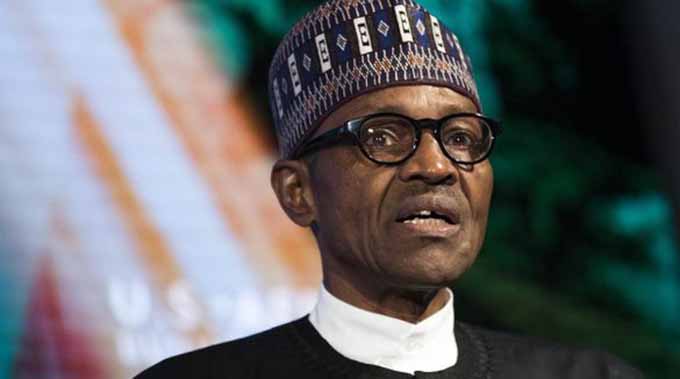

Raquel Navarro, Mr Alvarez’s wife, owned an events promotion company before the financial crisis. Now she works as a secretary, paid just above the minimum wage.

For people in this group, whom economists define as earning between two-thirds and double their country’s median income, the risk of falling down the economic ladder is greater than their chances of moving up.

“The progress of the middle class has halted in most European countries,” said Daniel Vaughan-Whitehead, a senior economist at the International Labour Organisation in Geneva. “Their situation has become more unstable, and if something happens in the household, they are more likely to go down and stay down.”

The hurdles to keeping their status, or recovering lost ground, are higher given post-recession labour dynamics.

The loss of middle-income jobs, weakened social protections and skill mismatches have reduced economic mobility and widened income inequality. Automation and globalisation are deepening the divides.

Europe’s social safety nets have traditionally offered protection, but even these are being reduced as deficit-reduction policies required by the European Union kick in. That unravelling, in part, explains the populist discontent in Europe.

“Politicians haven’t created measures to help those of us in the middle get back on our feet, and we’re a big group,” said Mrs. Navarro, her frustration clear.

“What happened to me has happened to many people I know,” she said, citing friends and neighbours who have confided their woes. “When we get together, we call ourselves ‘loss invisibles’ — the invisibles,” she added. “We are the forgotten ones.”

In Spain, it seems as if this should not be happening. The country was feted by European policymakers as a model for the recovery, having tightened its belt to exit a deep recession. An overhaul, which included sweeping labour law changes in 2012 that gave employers more flexibility to fire and hire, helped revive the economy.

Spain’s economy grew faster than those of France and Germany last year, at a 3 percent annual pace. Unemployment fell last month to 14,4 percent, the lowest in a decade and down from a staggering 27 percent in 2013.

But interviews with over a dozen workers revealed a deep-seated disillusionment with the recovery and the quality of jobs emerging from it.

The changes in labour laws weakened job protections as well as earnings. With millions looking for work, employers could offer lower salaries, making it harder for people to regain or maintain living standards. — NY Times.

Comments