Why colonial symbols are loathed in Africa

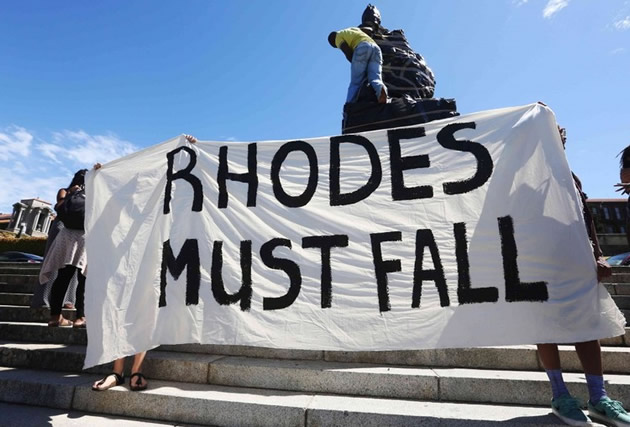

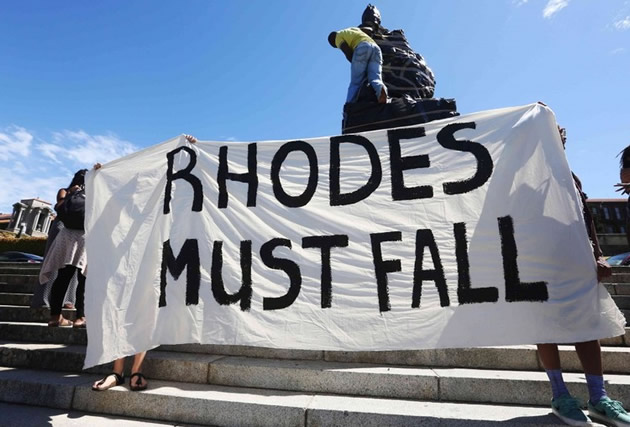

Statues, like this one of Cecil John Rhodes being covered up, rub salt into the wounds of the once- conquered people of Africa and their descendants

Baffour Ankomah Baffour’s Beefs

The recent campaign in South Africa against colonial statues is just the tip of the iceberg in an Africa-wide phenomenon that is likely to result in the removal of offending statues of colonial figures from public places. With similar statues removed in Zimbabwe and Namibia in the recent past, other

countries are bound to follow suit, writes Baffour Ankomah.

At No. 33 Fitzroy Street in central London, there is an ongoing exhibition featuring artifacts from Italy, one of which is the marble statue of Primo Carnera’s head. Carnera became Italy’s most famous athlete and champion of the world during the reign of Mussolini, who declared him a national hero.

The advert promoting the exhibition begins with a profound line: “Every object tells a story.” If you repeat this line twice in your head, you begin to see why South African students no longer want the colonial statues adorning their campuses and cities, and want them removed.

“Every object tells a story” indeed. So what stories do the hundreds of colonial statues in public places in African cities tell?

Generally they tell the stories of conquest, the subjugation of the African people and their lands by foreigners who came from across the seas. In that context, the statues rub salt into the wounds of the once- conquered people of Africa and their descendants.

As a result, according to the black students of the University of Cape Town (UCT), the contentious statue of Cecil Rhodes that used to sit, head in hand, looking out over the UCT’s rugby grounds was a “symbol of white supremacy” that offended their sensibilities, and therefore they wanted it removed. And it was removed.

Chumani Maxwele, the student who started it all by throwing a bucket of human excrement at Rhodes’ statue, advanced a powerful argument: “As black students,” he said, “we are disgusted by the fact that this statue still stands here today as it is a symbol of white supremacy.”

That feeling is universal across Africa, and it was not a surprise that thousands of other black South Africans agreed with Maxwele. “It should have long been removed,” Xolela Mangcu, a UCT academic and biographer of Steve Biko, said of Rhodes’ statue.

“Rhodes was probably one of the worst colonisers both in word and deed,” Mangcu, who also writes for New African, added. “His legacy speaks for itself. He laid the template through the native reserves, the pass laws, and saying extremely racist things. For his statue to have pride of place is anachronistic.”

Tuberculosis, land and

diamonds

So what did Rhodes do exactly? According to Wendel Roelf of Reuters, Rhodes, who was born in 1853, the son of a Bishop’s Stortford clergyman in England, “went to South Africa because of adolescent ill-health. [He] founded the De Beers diamond empire, became one of the world’s wealthiest men and rose to be premier of the Cape Colony in 1890.

“He began the policy of enforced racial segregation in South Africa and allowed the newspapers he controlled to publish racist tracts. He died in 1902, aged 49, and was buried in the country that bore his name, Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. Rhodes “donated” the land on which the UCT campus is built. The statue, unveiled in 1934, depicted him in a seated position and has been a source of discontent for years.”

So, first, Cecil Rhodes started “the policy of enforced racial segregation in South Africa”. In other words, he started what became the obnoxious apartheid regime in that corner of Africa.

Second, he “donated” the land on which the UCT campus is built. The young man who arrived from Bishop’s Stortford with no land but plenty of tuberculosis in his lungs (as some historians have cared to point out), yet was able to “donate” the land on which the UCT campus was built! How he came by the land (by conquest) is the question that now haunts the descendants of the colonialists in Southern Africa.

Martin Plaut, another white journalist, writing on April 16 2015, made things even clearer. “Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902) was the supreme imperialist,” he wrote. “A mining magnate who made a fortune from South Africa’s diamonds, [and] dreamed of a British empire from the Cape to Cairo. It was his private initiative that led to the conquest of Zimbabwe. He planned a raid on Paul Kruger’s Transvaal republic, which was a precursor to the Anglo-Boer War.”

Plaut went on: “Rhodes’s legacy is a source of ambivalence for some. Rhodes University in Grahamstown, Eastern Cape province, was created with Rhodes’s wealth and named after him. His will also created the Rhodes Scholars to educate future leaders for the world at Oxford University [in England]. In 2003 the Rhodes Trust joined in the creation of the Mandela Rhodes Foundation, which provides scholarships for students studying at African universities.”

So what was Plaut saying in so many words? The best interpretation was provided by Trudi Makhaya, a South African who studied as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford. She commented that the “contradictions, [between] Rhodes the pillager and Rhodes the benefactor, are a symbol of our country’s evolution towards a yet to be attained just and inclusive order”.

But to Adekeye Adebajo, a Nigerian Rhodes scholar and executive director of the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town, Rhodes the pillager completely cancels out Rhodes the benefactor. “At the time I got the Rhodes scholarship,” Adebajo said, “all I could think about was getting a good education and fighting for pan-Africanist issues. This wealth was stolen from Africa when Rhodes plundered the continent, so I felt absolutely no guilt about using the money to criticise what he stood for.”

Statues of “good

imperialists”?

It is the sum of these four simple words that is at the heart of the colonial statues debate! First, many Africans hasten to point out that Africans do not mind building statues for “good imperialists” who came to do good, or allowing the statues of such good imperialists to occupy places of honour in African cities.

For example, in the middle of the 1930s, Ghanaian chiefs and their people collected money and went as far as the Municipal Cemetery at Bexhill-on-Sea on the south coast of England to build a red granite headstone for Sir Gordon Guggisberg, the colonial governor of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) from 1919 to 1927, who, against stiff opposition from London, tried to develop Ghana with all his heart and with all his soul.

Of Jewish descent, Guggisberg’s forward-looking attitude to the development of the Gold Coast led to his adopted country, Britain, virtually disowning him. London stopped him from what he intended to do for Ghana, and when he died a pauper in 1930, he was buried in an unmarked grave. This shocked and angered the chiefs and people of Ghana who went all the way to Bexhill-on-Sea to erect the headstone befitting the stature of the man they called the “Beloved Imperialist”.

The inscription on the headstone still reads: “To the everlasting memory of Governor Sir Gordon Guggisberg who died in 1930 at Bexhill. This memorial was erected by the Paramount Chiefs and people of the Gold Coast and Ashanti.”

To many Africans, the words “beloved” and “imperialist” would seem incompatible. In fact, Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, famously said “a good imperialist is a dead one”. But a “beloved imperialist” is how Ghanaians remember Guggisberg – “for having set the country on a better and faster course, in both infrastructural development and localisation of the civil service, towards eventual independence than was the lot of any other African colony before 1939”.

This establishes the fact that not all imperialists were bad. As such, Guggisberg’s statue still stands proudly in front of the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra, Ghana’s number one hospital – the hospital that Guggisberg built.

However, in contrast to Guggisberg, Cecil Rhodes and imperialists of his ilk left ambivalent legacies that affront African sensibilities. Thus to many Africans, Rhodes the Pillager makes a complete mockery of whatever good Rhodes the Benefactor did. As such, when Rhodes’ statues continue to stare down at them in public places, Africans get squeamish.

Unfortunately those who built the colonial statues did not take African sensibilities into consideration. Their heroes were not the heroes of the Africans, but because they were in power, they used the power of incumbency to do as they pleased, sometimes arrogantly.

Lothar von Trotha

Take for example, the now removed statue of Lothar von Trotha, the German Kaiser’s murdering agent who supervised a killing spree in 1904-08, in which over 80 000 Herero and 10 000 or so of the Nama people were annihilated in Namibia in the first genocide of the 20th century.

After the killing spree, the German colonisers arrogantly built a monument supposedly for their war dead, in front of the National Museum in Windhoek, and on top of the monument they put a statue of Von Trotha sitting haughtily on a horse with a gun in his hand.

What is worse: This monstrous statue continued to mock the Africans from 1908 until 2013, a good 23 years after Namibia’s independence in 1990, when it was removed amid stiff opposition from the economically powerful community of German-Namibians, who raised an uproar. Despite the uproar, the Namibians have replaced the statue with a proper monument honouring the African victims of the 1904-08 war, with the slogan “Their blood watered our freedom”.

When they raised the commotion, the German-Namibians deliberately overlooked how the Jewish people cannot allow a statue of Adolf Hitler to stand in front of the National Museum in Jerusalem. If nobody can imagine such a thing in Jerusalem, why should the Africans allow it in Windhoek or Cape Town or Johannesburg or Nairobi or Harare?

Even more so when, if the shoe had been on the other foot, the German-Namibians or their cousins in the wider Western world would not allow such statues to stand. For example, in 2003, when the Americans and the British conquered Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, one of their first acts was to pull down Saddam’s statues across the country. The most famous one in Firdaus Square in Baghdad had its head draped in the American flag before it was pulled down by American troops in the presence of scores of international journalists.

Today no one remembers the glorious days of the Africans (called Moors) and their Muslim brothers who colonised the Iberian Peninsula from 771 to 1492 and brought light, education and development to Europe in the 721 years they ruled over what are now Spain, Portugal, Granada, and Sicily?

“Into Europe came the advances of an empire more immense than those of Alexander the Great or Rome at its height,” testifies the African-American historian, Ivan Van Sertima. “Rice was introduced into Europe by the Moors in the 10th century, cotton by the 9th”.

The African invasion of Europe was totally different from the European invasion of Africa, because as Sertima points out: “The Moors did not suppress the languages of the people of Al Andalus [as Iberia was known], they did not outlaw their sacred customs, they did not turn Iberia into a sweatshop, its fertile lands a mere source of raw materials for the Muslim international elite. They did not destroy their legal system, rob them of their political rights, deny them their claim to humanity. The only thing they did insist on was a say in the election of the Catholic bishops since the rival power of the church could undermine Muslim power and authority.”

And yet when Moorish rule in Iberia finally ended on January 2 1492, the victorious alliance of Queen Isabella of Castile and her husband King Ferdinand II of Aragon systematically erased all traces of the Moors in Europe, except the large palaces, castles and mosques they built that could not be destroyed because of their sheer size.

Otherwise all the statues and everything that could be destroyed was destroyed because it was all seen as the work of conquerors from Africa. Comparing the illiteracy of the Christian Europeans to the learning and erudition of the Moors at the time, Jan Carew, another history writer, wrote: “At a time when the most significant provinces of Moorish Spain contained libraries running into thousands of volumes [99 percent of Europe was illiterate at the time], the cathedrals, monasteries and palaces of Leon, under Christian rule, numbered books only by the dozen. The paltry number of texts the Christians did possess were almost all devotional or liturgical.”

Sertima adds that “the narrowness of vision this produced among leaders of the church and state was to have catastrophic effects. It led to the massive burning of African and Arab books under the order of Cardinal Ximenes de Cisneros. It inspired a similar bonfire of the books of native Americans. Bishop de Landa exhorted his followers in the Yucatan ‘Burn them all – they are works of the devil’.”

According to Sertima: “The destruction of the Moorish libraries was particularly vicious because it was not only inspired by religious narrowness and bigotry. Hatred of the dark invaders kindled the bonfires. The church at the time too saw most of this foreign learning as something evil, even demonic.

“The number system that we use today, for example, brought in by the Moors, was seen as late as the 17th century in some parts of Europe as the sign of the devil. It became a religious mission for men like Ximenes and his successors to erase from history all memories of the Moors. Ximenes even induced the Spanish sovereigns to outlaw the public baths [introduced by the Moors], making cleanliness antithetical to godliness.”

So, if the good works of the conquering Moors were burnt and erased by the Europeans, how could the Africans, in contrast, be told now to honour Von Trotha and Cecil Rhodes and the other bad imperialists in statue form?

Von Trotha had come to Namibia on the back of other punitive expeditions in China and German East Africa (today’s Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi). He wrote to the German governor of the then South West Africa, Theodor Leutwein, who was against the killing of the Herero, saying: “I know enough of these African tribes. They are all alike insofar as they only yield to violence. My policy was, and still is, to perform this violence with blatant terrorism and even cruelty. I finish off the rebellious tribes with rivers of blood and rivers of money. Only from these seeds will something permanent be able to grow.”

For standing up against the impending cold-blooded murder of the Herero, Governor Leutwein was relieved of his military and civil authority and asked to return to Germany in disgrace.

On 23 November 1904, Trotha’s fellow murderer, Count von Schlieffen, wrote to the German chancellor, Prince Bernhard von Bulow in Berlin, telling him, “one can agree with Trotha’s proposal that the entire nation should be annihilated or driven from the country” because, to him, the Herero had “forfeited their lives”.

Schlieffen added for good measure: “The race war, once it has broken out, can only be ended by the extermination/annihilation or complete subjugation of one of the parties.” And true to his word, “one of the parties” – the Herero, 80,000 of them – were exterminated by the end of the “race war”!

Thus, if today Namibian streets are still named after Schlieffen and other such German colonisers when no street in Germany or anywhere in Europe is named after any African hero, it speaks of supremacy and conquest. And it is this kind of “supremacy” that the South African students and other Africans are fighting against.

It is the same supremacist idea that informed Cecil Rhodes’ insertion of the following paragraph in his will: “I admire the grandeur and loneliness of the Matopos in Rhodesia, and therefore I desire to be buried in the Matopos on the hill which I used to visit and which I called the ‘View of the World’ in a square to be cut in the rock on the top of the hill, covered in a plain brass plate with these words thereon: ‘Here lie the remains of Cecil John Rhodes’, and accordingly I direct my executors at the expense of my estate to take all steps and do all things necessary or proper to give effect to this my desire, and afterwards to keep my grave in order at the expense of the Matopos and Bulawayo Fund hereinafter mentioned.”

This paragraph ensured that when Rhodes finally died in 1902, his body was carried from South Africa to Rhodesia (a country he never lived in but which he named after himself), and ultimately to the exact spot described in the will, on top of the mountain he called the “View of the World”, which happens to lie in pristine surroundings in a corner of the Matopos National Park, 46 km from Bulawayo.

Rhodes had chosen the “View of the World” with care, because he knew that he would be lying on top of the sacred burial grounds of the Ndebele people below the mountain, where the remains of King Mzilikazi, the famous leader of the Ndebele and predecessor of King Lobengula whom Rhodes’ agents had tricked on their way to conquering Zimbabwe, lie. So, today, even in death, Rhodes is lying on top of Mzilikazi, a triumph of some sort acting as a continued defeat of, if not insult to, the Ndebele. Strangely in 2008, Rhodes’ grave found an unlikely ally in President Robert Mugabe when some ordinary Zimbabweans mounted a campaign to dig it up and ship Rhodes’ remains back to Bishop’s Stortford.

Mugabe’s government did not yield to the strident campaign but rather took the view that Cecil Rhodes, though a bad man, was part of the country’s history and his grave should stay at the Matopos.

That notwithstanding, Mugabe’s government, years earlier, had ordered the removal of Rhodes’ statue from the heart of Harare at the square that used to be named after him. Cecil Square, now called Africa Unity Square, “sits at the heart of the essence of what was Rhodesia and the very change in its name suggests the attempts that were made to extirpate the vestiges of colonialism from our national system”, says Mabasa Sasa, the acting editor of The Sunday Mail in Harare and a New African writer.

Cecil Square was renamed in 1980 and Rhodes’ statue, that commanded all it surveyed from atop a high plinth at the centre, disappeared altogether.

The Square was designed by the Rhodesians in the format of the British flag, the Union Jack, and that design exists to this day, even though the name was changed to Africa Unity Square.

But in place of Rhodes’ statue, a new Africa unity monument was built to reflect the thinking of the new Zimbabwe and its long-suffering people, even though David Livingstone’s statue in white marble was allowed to stand, and still stands, in the courtyard of Munhumutapa House, the Office of the President and Cabinet (a complex of offices in Harare housing the Cabinet Office, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Vice Presidents’ Offices, and the Ministry of Information).

However, on the scale of badness, Livingstone, compared to Rhodes and Trotha, can be excused as having been a benign character. Though it has now been established, via a letter found in recent years in Zambia’s national archives written by Livingstone, that British colonisation of Central Africa was the ultimate goal of his “missionary work” in that part of Africa, Livingstone is seen as having done more good for Africa than bad, and a much better person than Rhodes.

As such, even though he arrogantly claimed to have discovered Victoria Falls and named it after his queen, Victoria, although the local Africans had known the falls for aeons as Mosi-a-Tunya (meaning “the smoke that thunders”), Livingstone is still allowed to stand in two granite statues on either side of the falls, which now form the border between Zimbabwe and Zambia.

It is the arrogance of people like Livingstone and other European explorers who claimed to have “discovered” African landmarks that were already in use by the local people, that angers modern Africans who want the names of the landmarks changed back their original African names.

In that context, the statues debate in South Africa, and the subsequent removal of Cecil Rhodes’ statue from UCT, is just the tip of the iceberg of emotions gathering across Africa. Therefore, the descendants of those who built the statues would greatly help the situation by not raising an uproar to inflame the African passions even the more. – New African magazine

Comments