Unsung heroes of the First Chimurenga

Obert Chifamba Correspondent

FROM a distance, a geographer can easily be cuckolded into thinking it’s a trigonometrical beacon while weather enthusiasts may think it’s a wind vane, on an unusual rock promontory.

It is only upon reaching the foot of the mountain that one is confronted by a rusty placard inscribed “Fort Martin”.

Below the inscription is a list of names of Rhodesian settlers slain in the first organised resistance to colonial settlers, dubbed First Chimurenga — 1896 to 1898. And there are 13 graves bearing name tags of the fallen settlers.

There are also four more separate graves that are conspicuous by the absence of anything to identify the occupants lying inside.

One of the graves houses the remains of a great Shona chief, Chinengundu popularly known as Mashayamombe, minus his dread-locked head that was decapitated and taken to Europe. Like the Biblical Samson, the settlers believed there was magical power in his hair.

Until the early 1960s Chinengundu’s head was reportedly been kept in a museum in Bulawayo while current information on the matter suggests that the head is now at Buckingham Palace in England while the remains of Chifamba, Chinengundu’s chief military strategist, is believed to be interred somewhere on the mountains unaccounted for and of course, unmarked.

Fort Martin is near Mupfure River in Mhondoro communal lands and was a vintage point from which settler forces observed enemy movements, it was from here that they launched forays into Mashayamombe’s territory and it was also from here that they fortified their defence positions.

Of course, it is the deafening silence on the exploits of the two great heroes and their equally militant cousins in the Mashayamombe clan — Muzhuzha, Kakono, Muchena and Kawara —that easily boggles the mind when their erstwhile “partners in crime”, Nehanda and Kaguvi, are readily mentioned at every possible opportunity.

Mashayamombe’s resistance story begins when his cousin, Headman Muzhuzha defies a directive to pay taxes and provide free labour to white settlers in 1896 and consequently receives a hiding right in front of his subjects from David Moony, Native Commissioner for Hartley (now Chegutu).

Upon learning of this embarrassing incident, Chinengundu and Chifamba reacted swiftly and killed Moony and two other white men who had come looking for him. This attack provoked vicious reprisal attacks from the white settlers signalling the beginning of what was to become the First Chimurenga in Mashonaland.

Chinengundu and Chifamba were sons of Choshata, who like Muzhuzha, Kawara and Kakono, were descendants of the Mashayamombe clan. Muzhuzha’s village was part of a cluster that included Muchena and Chifamba Villages, to name a few, which formed the stronghold of the Mashayamombe clan along Mupfure River.

On June 21 1896, a Rhodesian infantry was sent to attack Chinengundu but was repelled. Another force from Salisbury came and burned Chifamba and Muchena’s villages. They too were stopped as they entered Mashayamombe’s stronghold on the banks of Mupfure.

Mashayamombe pursued them and killed the man captaining the attack, which purged the area of settlers except for a small number at Hartley Hills. He laid siege to this group at Hartley Hills too. It is not clear when and where Chinengundu captured a white woman with whom he lived in the mountains as man and wife. The woman was reportedly kept with a clean shaved head.

Rhodes sent a force to rescue the miners and it was at that point that Mashayamombe broke his siege and went back to his fortress along the Mupfure River.

History has it that one Lt Colonel Edwin Alderson of the Queen’s West Kent Regiment was sent to Rhodesia commanding four companies of mounted infantry to deal decisively with Mashayamombe with 622 men at his disposal, 311 of them regular imperial troops.

Another account says he got additional troops to take his tally to 1 000 men for the decisive assault. But the hilly Mashayamombe country divided the troops into separate units and as they slithered down the sloping ground, volleys of gunfire, fired in rapid succession, greeted them.

The Rhodesians’ casualties were mounting by the day, which dampened hopes of dislodging Mashayamombe’s troops from their cave hideouts. After battling for three days, the settler force gave up, at least temporarily.

Mashayamombe on the other hand settled down when the rains came to plant his fields but Rhodes took advantage of the lull in hostilities to replace the imperial troops with the British South African Police, which established a fort at Mashayamombe’s kraal and named it Fort Martin. They raided and destroyed Mashayamombe’s crops.

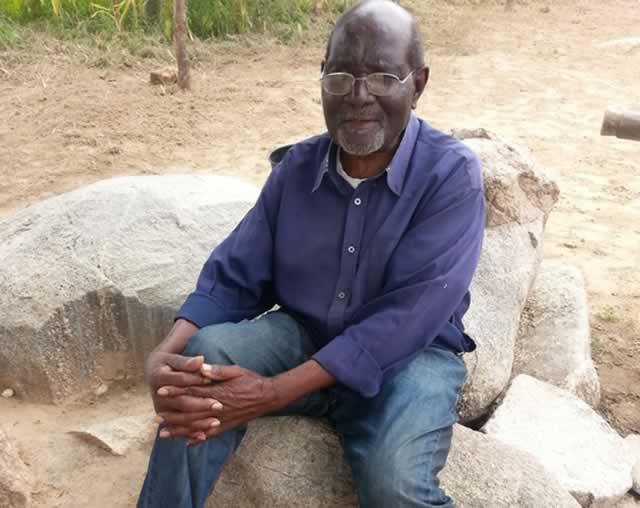

Mashayamombe attacked Fort Martin, but failed to capture it. Then the pioneers sent overtures for a truce to buy time while they organised another attack. They came back the following month. A descendant of the Mashayamombe clan, Bornwell Chifamba said the ensuing battle also seemed unwinnable until Chifamba, who was shooting through a hole from their own fort, was sold away by a nephew only identified as Gutu.

“The trooper who killed Chifamba snipped him from a tree but he did not die on the spot. He ran and told Chinengundu that he had been shot and was going. He then disappeared and was never seen again along with his gun.

“Seeing that he was now exposed, Chinengundu took his own life and the whites only came to find his lifeless body,” said Chifamba.

They proceeded to cut his head off and took it with them. It is believed that the beheading of the famous rain-maker was to de-link his legacy from his descendants and the people of Zimbabwe who revered his divine powers in the past. Mashayamombe had come to be known as Chinengundu on account of his dread-locked head, as Shona people call dreadlocks ‘‘ngundu’’.

The whole idea was to defile the great leader and by taking away his head and his walking stick, they wanted to make sure there was not any kind of communication with the living spiritually but his descendants have continued to hold rain-making ceremonies at his grave every year up to this day.

They even authorised the burial of three Second Chimurenga freedom fighters — Foni Kadiki, Thompson Giga and Peter Kapfunde — next to his grave. Fort Martin also became the burial site for settlers that died in the First Chimurenga war. Today there are 13 graves of the colonialists on the site.

Just five kilometres from Fort Martin, there is a famous pool called Kaguvi that is situated along Mupfure River and was named after revered First Chimurenga revolutionary Sekuru Kaguvi, a spirit medium of the Mwendamberi clan. It is the place where the Mashayamombe Heroes Acre was established after six war collaborators were bushwhacked by a Rhodesian reconnaissance patrol on the dawn of 29 May, 1979, as they were taking supplies to a ZANLA guerrilla hideaway along Mupfure River.

The six — Pedzisai Marunga, Jane Mandizvidza, Garikai Chifamba, Maxwell Hwata, Eunice Chifamba and Anne Chinouya who came from Churu Village, which is just a stone throw away from Mupfure River and was christened kuMoza during the war because it was the place where all freedom fighters coming into the area would first visit and was also the conduit for supplies — were subsequently buried near Kaguvi pool and every year people converge there to commemorate Heroes Day.

Sadly, Chinengundu and Chifamba have to watch these commemorations and celebrations from their spiritual realm and not see even a single soul coming to their fort to pay homage except when the rain season is approaching. It is also interesting to note that the first shots of the First Chimurenga in Mashonaland were fired in Mashayamombe’s area and the last shots of the Second Chimurenga were also fired there!

Comments