The senseless fight of two African bulls

Mondhli Makhanya Correspondent

If ever there’s a geopolitical rivalry that makes no sense, it has to be the South Africa-Nigeria contest. For about two decades, the two nations, who should be close strategic allies, have been jostling for playground supremacy. National rivalries are, in themselves, not unique and have been with us since humans started walking upright.

However, most of them are founded on concrete historical animosity and real, present-day competition.

Britain and France fought over trade routes and colonial dominance. In the post-colonial period, the rivalry has been over who wields greater political, economic and cultural clout in the developing world.

Political and cultural influence translates into opportunities for the respective countries’ corporations and, therefore, economic benefit for these countries.

Germany has had tense relations with both these European powers.

These have their roots in medieval territorial conflicts and the colonial period, but were exacerbated by the two world wars of the 20th century.

The age-old tiff between Russia and the US was entrenched during the rise of the 20th-century “isms” – capitalism and communism.

With the Soviet Union serving as the lodestar of communism and the US seeing itself as the leader of free market economics, the two nations saw each other’s respective ideologies as the epitome of evil.

This rivalry has outlasted the fall of communism and Vladimir Putin’s drive to restore the pride of the defunct Soviet Union has served to intensify it.

In the eastern seas, there is the historical enmity between Japan and China that is rooted in centuries of raids and counter-raids. Pakistan and India’s tensions go back to the ugly partition at the time of independence from Britain.

With religion, massacres and a nuclear race thrown in, the relationship has become one of the world’s intractable stand-offs.

The point with the above examples is that you can trace the source of conflict. In a macabre way, they make sense.

Not so the Nigeria-South Africa relationship. In the days of the struggle, Nigeria was a major backer of South Africa’s liberation movements.

The country provided shelter, money and a voice for those who were fighting apartheid.

Regardless of whether a civilian or a military dictator was in power, Nigerians took South Africa’s struggle as their own. Close ties were forged between the Nigerian people and exiles who would later go on to run a free South Africa.

One would have assumed then that this would translate into cordial relations once South Africa became a free republic. It seemed natural that the two nations would complement each other’s strengths as regional hegemons and jointly lead the revival of the continent.

But it was not to be. Instead, a fierce rivalry ensued immediately after 1994.

The first cracks started appearing in 1995 when Nelson Mandela spearheaded the suspension of Nigeria from the Commonwealth after the execution of human rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa by Sani Abacha’s military government.

Given that the oppressive Abacha regime was hated by most Nigerians, this should have been welcomed by that country’s citizens as a quid pro quo act of solidarity.

At least that is how South Africans saw it. But Nigerians did not appreciate this “interference” and saw it as bullying behaviour by the new kid on the block.

The axis of power was no longer Nigeria/Egypt, as had been the case since the independence era. There was now a new vocal power on the continent. This new power had a huge industrialised economy, good moral standing on the international stage and the figure of Nelson Mandela as its devastating boxing glove.

The rivalry was to take on many forms as the years passed. South Africans joined the continental suspicion of Nigerians as a people prone to shady behaviour and the Nigerians sided with other Africans in characterising South Africans as better-than-thou imperialist wannabes.

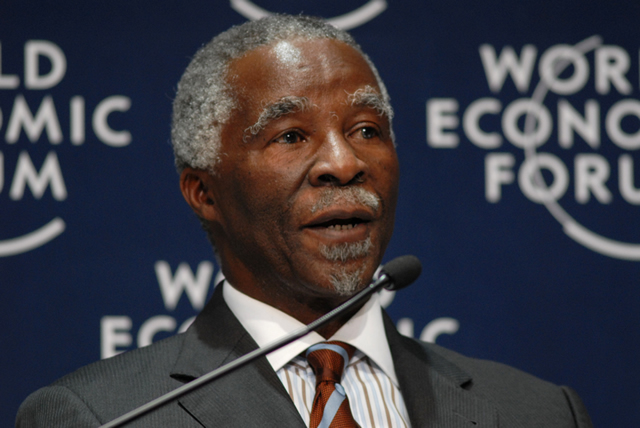

There was a brief respite during the tenures of Thabo Mbeki and Olusegun Obasanjo when these two leaders – with Algeria’s Abdelaziz Bouteflika – sought to create a united and enlightened African voice on the world stage. Together they argued for the reform of multilateral institutions and an overhaul of the world trade and investment infrastructure. But even at this point, there was behind-the-scenes jostling as to who would be the first to land a UN Security Council seat.

With the replacement of Obasanjo and Mbeki by lesser men, the standoff resumed. There have been fights over a million inconsequential things.

Then two weeks ago, in the wake of the death of 84 South Africans in the Lagos church building collapse, the rivalry took on a tragic twist.

In a moment of tragedy where the best values of ubuntu and brotherhood should have shone through, petty politics came into play.

It was arguably the lowest point in the relations between the two giants.

What is required now is for the leaders of Nigeria and South Africa to pause and ask who stands to gain from the senseless rivalry.

They will find that the answer is as stupid as juvenile playground punch-ups. — City Press.

Comments