The bane of power protectionism

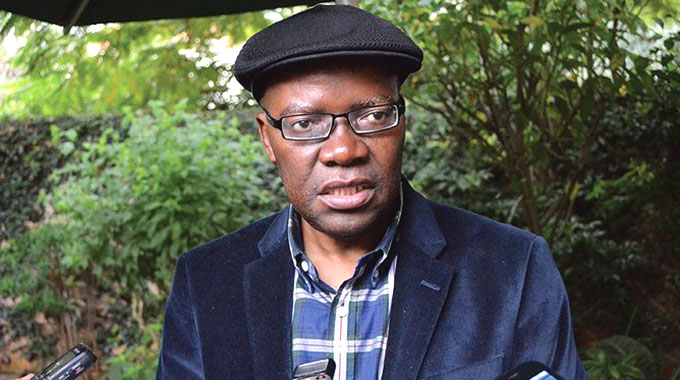

Reason Wafawarova on Thursday

COMMONLY protectionism has been viewed in academic circles as policies and actions of governments that seek to restrict competition in international trade, many times motivated by the intent to protect local businesses and jobs. Methods used include import tariffs, quotas, subsidies, nationalisation, tax cuts for local business, tax hikes for foreign investors, or direct state intervention in matters of trade.

I am not going to dwell much on economic protectionism as practised by Britain or France in the 19th century, or even the modern day hypocrisy of the United States, where free market economies are preached against the background of protectionist agricultural subsidies for American farmers.

Rather I want to discuss protectionism in Africa, sadly centred more on political interests than it is on the economic ones. In Africa we run politics more than we run economies, and that is quite normal.

Since the continent overthrew foreign political administrations of the colonial era, there has been this stultifying obsession with preservation of political power and privilege, and it is disquieting to note that next to negligible attention has been paid to matters of economic interests in post-colonial Africa.

Our economists are excellent mimics of Bretton Woods economics, and they are trained to specifically prune the continent into a massive client for patronising economic prescriptions from the West.

Our political leadership across the continent has largely left the planning of our economies to the IMF and to capitalist donors – most of them opting for the easier role of playing client administrators of donor and debt propelled economies.

We have failed dismally to leverage on the advantage of our vast natural resources, and we have had the older generation of political leaders who have despondently avoided the challenge of growing our economies – opting to focus on the more important preoccupation of preserving political security for themselves and their parties, or just playing donor-funded puppet politics to some powerful Western country.

One of the reasons the winner-take-all democratic phenomenon has not worked well for Africa is the tenacious infatuation with political power by some of our leaders.

Many of our countries experimented with the one-party state ideology immediately after independence, more to preserve political privilege and power than to ensure continuity of the goals and objectives of the liberation legacy, as much of the justification went at the time.

We had UNIP in Zambia, KANU in Kenya, and MCP in Malawi, among the parties that tried and failed to establish one-party states on the continent. The project failed to take off in post-independent Zimbabwe because the idea could not find traction within the ruling Zanu-PF.

We are back to winner-take-all politics in Zimbabwe and Kenya after brief stints of power-sharing inclusive governance – scenarios eventuated by political crises related to disputed election results in both countries. Some people have argued that the inclusive governments were more effective in the management of economies than the winner-take-all administrations are.

There are pros and cons to this argument, suffice to say the inclusive governments themselves were transitional in their very nature, never designed to provide a permanent alternative governance system. They came with set timelines and goals, like the drafting of new constitutions and carrying out of subsequent elections.

There are unpalatable implications that have come with winner-take-all democracy in Africa, some of them so dire that they have resulted in civil wars and other forms of internal instability.

Winning political parties have been known to use unorthodox means in consolidating power for themselves, and many times the opposition parties have hardly been allowed room to be an alternative voice to governance. Rather, opposition parties must suffer the loser’s blame, and often every gimmick possible is employed to ensure the perpetuity of a defeasible opponent.

Power protectionism is the mother of patronage politics, the bane of development, and the undoing of Africa’s accountability institutions. During Kenya’s inclusive government the coalition parties were all involved in ethnic-driven segregatory conduct, especially involving the appointment of key personnel in the top echelons of the civil service.

The whole idea of patronage politics is to reward blind loyalty, to establish patron-client politics, and the greater goal is unbridled political protectionism where all external competition against the incumbent authority is kept at bay by employing the services of state power.

In any mature democracy the ideal situation is to have meritorious and apolitical institutions of accountability, be these security institutions, administrative institutions, regulatory bodies or auditing authorities. Once such institutions are constituted in such a way that they begin to recognise and respect the unwritten law of impunity for powerful political elites, we must always remember the greatest loser is national development. This is why political protectionism and poverty are very good siblings.

We have seen winner-take-all politics leading to compartmentalisation of development in many African countries, and many times minority ethnic groups have been marginalised as the ruling elites find no good cause in committing any developmental efforts the way of a minority vote.

The continued splitting of the MDC is a clear result of the detrimental culture of political protectionism, especially on the leadership of Morgan Tsvangirai.

For years democratic principles have been sidelined as characters loyal to the dear leader have been imposed on the electorate ahead of popularly preferred candidates, and sometimes rules are changed to ensure the accommodation of undeserving or unqualified people whose only strength is their connection to the party leader.

The National Constitutional Assembly was reduced from a mighty conglomeration of great minds to a tiny Madhuku fiefdom because someone was obsessed with power protectionism. Now the depleted and exhausted outfit has been transformed into a stillborn political party, so clueless that even an eminent clown like Job Sikhala saw better than sticking around.

There is something in power protectionists that makes them believe in the kick the ladder away philosophy. They rise to positions of power, sit there at the top, kick the ladder away, and then they urge all others to climb up and make it to the top the way they did.

Power protectionists always believe that history is on their side, and they have an unrelenting conviction that historical glories override their current errors, regardless of their magnitude.

Power protectionists have very little time for constructive engagement in developmental affairs. They are often preoccupied with hunting down people perceived to be threats to their positions, or just accumulating for themselves through aggrandisement politics.

It is rather apprehensive to follow Zanu-PF politics at the moment. From chaotic elections of provincial executive members last year to inconceivable selection criteria for aspiring contestants for the upcoming congress, one wonders what has become of the revolutionary party.

Who in Zanu-PF’s current central committee had to prove a 20-year membership before they were elected or appointed? There are at least four ministers who sat in Zimbabwe’s 1980 Cabinet who are still in government today, and hardly any of them was beyond 35 years at the time. It is disheartening to see a party that started off with youngsters holding fort in its affairs evolving into a power protectionist outfit that seemingly wants to shut out young blood in the name of protocol and tradition.

One would have thought the party has a constitution it adheres to, not some ad hoc regulations authored and designed by interested and excited parties with indisputable vested pursuits.

It is going to be hard for a 25-year-old Central Committee aspirant to prove that they started serving in the party structures at the age of five, and yet this is exactly what they will have to do if the screwy regulations are to prevail.

The kick away the ladder mentality is not only detrimental to Zanu-PF’s continuity as a revolutionary party, but also a bad sign for the country’s commitment to development.

When merit is overridden by tradition and history it is hard to imagine innovation of any kind. Seniority, tradition and history are virtues that must be added advantages to the core principle of merit, and any meritorious person will not even think of shutting out competition, especially when they have age and experience to their advantage.

What has happened to the good old days when young unknown aspirants used to face the humiliation of electoral defeat at the hands of renowned party stalwarts, or those days when uncaring senior politicians used to be outed by promising youngsters popular with the masses? The later scenario is now officially described as “disrespect” in Zanu-PF circles, and frankly that is not a funny joke.

Ratification elections are not democratic by their nature. They are the kind of elections designed to manufacture mass consent for the will of a few but powerful elites. When competition is stifled and when competent competitors are eliminated along the way to an election of any kind, what you have in the end is a ratification or rubber-stamping of an unpopular political set-up.

This has been the bane of Zimbabwean politics from across the political divide. The role of senior politicians must be to nurture and groom youngsters in line with the ideology and goals of the political organisation to which they belong.

Political parties are neither monarchical nor traditional organisations. They are modern democratic political set-ups governed by the majoritarian will of their membership. It is important that such will is not be manipulated or tampered with.

The preach and patronise politics where some people, because of historical past glories or age seniority decide to anoint themselves as custodians of the people’s will can only derail us as a nation. Our history’s glory is a product of departed and living cadres whose idea of making history was to shape a better future for coming generations. It is sad when some among us shamelessly endeavour to abuse the same history in threatening the future of the country.

For Africa to move forward in a progressive manner we need to change our focus to developmental politics. We must not preoccupy ourselves with power politics, enthroning into our governments powerful rhetoricians with no idea on how to grow economies or provide facilitation for environments conducive for innovation and meaningful partnerships with other global economic forces.

We need to confront the powerful countries with a new generation of economically oriented leadership, different from the traditional aid-addicted begging bowl holders to whom Western leaders had gotten so used to patronise.

It is time to confront the West with demands of workable partnerships, not the patron-client relations that have prevailed for so long on our continent.

Africa we are one and together w e will overcome. It is homeland or death!!

REASON WAFAWAROVA is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia

Comments