Indigenisation and libertarian socialism

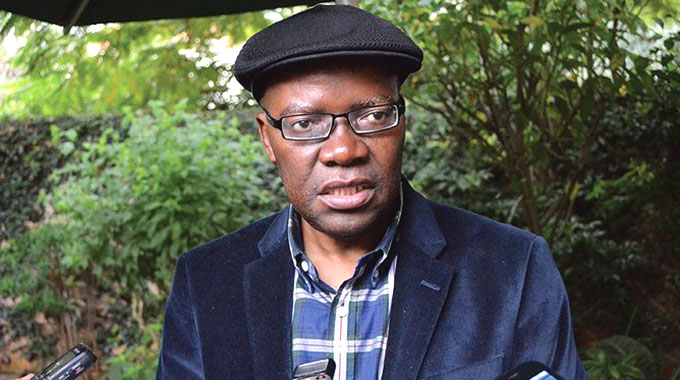

Reason Wafarova On Thursday

WE are in a telling dilemma regarding where our economy is going. From an economic ideological perspective, we are stuck between classical liberalism and libertarian socialism. If we for a while agree that our popular but yet to be fruitful policies of land reform and indigenisation fall within the confines of capitalism, then we may have to argue that we are stuck between blatant liberal capitalism and state capital- ism.

From an ideological viewpoint the meeting point between classical liberalism and libertarian socialism is the consensus that state functions are repressive in business, or in economic affairs in general.

The classical capitalist will advocate a free market economy, completely propelled by private capital.

The libertarian socialist will insist that state power be eliminated in favour of democratic organisation of the industrial society, with direct control over all resources and economic institutions.

When we embarked on the land reform programme the slogan was very simple: “land to the people”.

The simple message was that our people were taking control of the land.

Little did we know that some among us would abuse State power to maintain control of the land, by blatant abuse of offer letters.

So we read in the media that 15 years after our people were resettled, some people are still inexplicably rocking up at resettlement farmlands wielding eviction notices and offer letters unscrupulously acquired from our power corridors.

In 2012 we celebrated when the State announced that it had set up 59 Community Share Ownership Trusts across the country, telling our ever most believing villagers that the schemes would immensely benefit our rural communities, and the language spoken was in terms of tens of millions of dollars accumulating in community trust funds – all leading to enormous developmental projects that would create prosperous villages where everybody would live happily ever after.

Our free promising politicians proudly announced that the State would facilitate the empowerment of our villagers, and they made good their promise by speedily setting up community boards of trustees – ostensibly to preside over the promised millions of dollars.

As has become the norm, our opposition missed it by opposing the principle, not the practicality of the policy, and the electorate ignored.

Well, the only thing left of this impressive initiative seems to be the dramatic bickering between Justice Wadyajena and Saviour Kasukuwere, essentially arguing over a post-mortem audit of something that never was – a huge exaggeration of imagined community empowerment.

Direct control of resources and economic institutions by those who are considered entitled beneficiaries is a very popular phenomenon, but we are yet to see the success of such an initiative in Zimbabwe.

We have seen stunning successes in countries like Cuba and Venezuela, and in Gaddafi’s Libya.

It is quite reasonable to imagine a just system where workers’ councils play a huge part in labour matters, consumer councils determine the prices of goods, community assemblies determine the infrastructural development of their respective areas, and so on and so forth.

It would be great to see a system where the welfare of villagers is taken care of by proceeds from the Community Share Ownership Trust schemes, and for this reason rural voters gave Zanu-PF a chance to implement this irresistible policy.

We were told the CSOTs would bring to our people the kind of representation that is direct and irrevocable, with the representatives directly answerable to the community.

While classical liberalism can be dismissed as the undisputed vehicle of post-colonial imperialism, it is important that we ask ourselves whether libertarian socialism is feasible in a society like Zimbabwe. In asking ourselves these questions, we may have to introspectively assess the progress of our own policies, especially in the last 15 years.

Realists argue that popular communal control and popular communal benefit in matters of business are concepts exceptionally contrary to human nature, and they argue that those put in charge of such control would naturally seek personal benefit ahead of the collective expectation of all others. In this context, there is a tacit agreement that whoever is put in charge is bound to benefit themselves and their people more than anyone else, and to many this has become understandable.

Practising socialists have never been known to be popular among elites, and that is why self-sacrificing and honest politicians will always face the purge, or even get assassinated if purging is deemed impracticable, like what happened to Thomas Sankara in 1987.

It is those who join the bandwagon and adjust their lifestyles upwards once they join the power corridors that survive in the rewarding terrain of African politics.

Another argument put forward by realists is that collectivity is incompatible with the demands of efficiency. Communally owned economic processes are not driven by competition and selfish gain, and as such they are not carried out in the most efficient of manners. It is, however, hard on our part to even imagine that the CSOTs were ever communally owned, just security of tenure is increasingly becoming problematic for our resettled farmers, particularly the vulnerable A1 group.

Perhaps, let us consider the first argument. If people really want land, do they want the responsibility that goes with meaningfully utilising that land, or would they prefer to be employed by someone committed enough to develop that land for meaningful agricultural production, or as we hear now, prefer to let it out to others for a rental fee?

If people really want Community Share Ownership Schemes, are they prepared for the responsibility that comes with making sure such schemes are a success, or they are happier with someone in central government determining for them the pace and direction of infrastructural development in their community?

In asking these questions, am I not reviving the long discredited happy slave mentality, or promoting the notorious, dependency syndrome?

But we need an answer to why we have so much fallow land some 14 years after redistributing land to our people.

And we must have an answer as to why there is no meaningful evidence of any direct benefit for our villagers who are supposed to be smiling after our Government-launched the CSOTs three years ago?

Simply put, we need to see the benefits of our popular policies, especially those to do with the welfare of our people.

The nebulous nature of our empowerment policies does not speak well for the hope of the nation, and it is about time a more pragmatic approach to achieving tangible results was adopted.

We must denounce without fear the sophistic politician and intellectual who always brings up ways to obscure the facts when it comes to accountability.

He tells people that popular policies are a measure of the people’s emancipation, only to switch to yet another form of sweet rhetoric before any of the preached popular policies yields any tangible results.

Our politicians have been fervently committed to populism, but they have increasingly become ruthlessly notorious for shunning responsibility that comes with the implementation of their own policies.

We have to castigate any leadership that attributes to our people a natural inclination to chains.

We cannot have our resources being dangled as some form of carrot given at the benevolence of an unyieldingly controlling political elite. There is a world of difference between economic empowerment and induced loyalty, and as a nation, our people are fed up and done with the later.

Our people are ready for the land reform programme, and so are they for economic empowerment of the indigenous person. There is no doubt about that.

It is our political leaders who believe that there is incessant peace in the poverty of our people. They believe there is an understandable sense of repose enjoyed by our people in their chains. To most of our politicians the best our poor people deserve is some recklessly promised hope.

We are aware of how our people scorn at the voluptuousness of our corrupt political leadership, but our politicians are convinced that it does not behove the voter to reason too much about accountability.

So our people are pointed the direction of Western detractors and their genuinely ruinous illegal economic sanctions. Rarely do we ever get our people’s emotions whipped towards the accountability of the politician in power.

Emancipation can never come to our people on the basis of them being ripe or mature for it. One cannot arrive at the maturity of emancipation without having already acquired the emancipation. That is why we needed to acquire land before we could talk of expertise in using that land.

We must come up with a pragmatic investment policy that will create entrepreneurship expertise in our people, and it is heartening to hear President Mugabe making strong indications that investment laws will need to be revised towards the way of practicality.

There is a huge difference between a workable policy and an impressive social aspiration, and I believe we are heading the way of embarking on the road to pragmatism in public policy.

It is given that the first attempts at emancipation are bound to be painful and dangerous, even more precarious than the previous conditions, and we are aware of this through what happened to Zimbabwe’s agrarian sector after the year 2000.

But we must understand that one can only achieve success through one’s experiences, and it is important that our people are given the chance to pursue such experiences, including the failures that come with the long journey to success.

No rational person will approve of hunger and famine, or countenance unemployment, especially if perceived as caused by human misjudgment, and this explains the 2008 protest vote against ZANU-PF.

Nothing will ever promote indigenisation of the Zimbabwean economy more than indigenisation itself.

Of course, those who have so often argued about the unripeness of the black person will not accept this truth.

We have a duty as a people to guard against perpetual incapacity to run our own affairs in a successful way.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

• Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia

Comments