Establishment, recruitment, and graduate placement of NYS

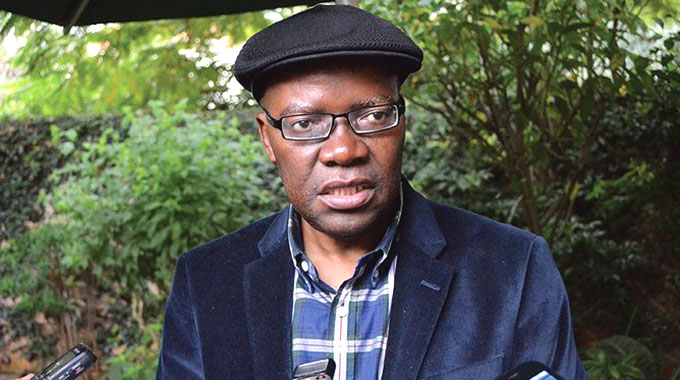

Reason Wafawarova on Monday

THIS will be the last of my National Youth Service instalments, unless of course there arises any need to explain anything else further than what has already been written in the scope of this column.

I will begin by explaining the establishment of the NYS programme, as I knew it between 2001 and 2004.

At its inception the programme was set up as part of the youth development portfolio, and it was a section within the larger Youth Development Department.

The head of the department was a director, otherwise known as deputy secretary, reporting directly to the permanent secretary of the ministry.

David Munyoro, who had spent many years under the Local Government Ministry as Provincial Administrator in Mashonaland Central and Manicaland, was appointed Youth Development Director after Minister Border Gezi took over the ministry in August 2000.

The two had worked together in Mashonaland Central.

Under Munyoro there was a Deputy Director (Youth Development and Vocational Training) and another Deputy Director (National Youth Service). A Mr Mutema held the former role while Rtd Brigadier Boniface Hurungudo was responsible for the NYS.

There were other directors and deputy directors in the ministry, namely Sensely Chatiza and his deputies in the employment creation department, Rachael Simbabure and her deputies in the gender department, and Innocent Mataruse and his deputies in the finance and human resources department.

But I will limit this piece to the NYS establishment only.

At the inception of the programme only the Deputy Director NYS was recognised in the overall Public Service Commission Establishment. He was the only NYS employee on record.

All other departments and sections in the ministry had fully established positions roles and positions down to the registry clerk and the cleaners.

Two colleagues and myself were the first people to be appointed to work under Brigadier Hurungudo. One of the two colleagues had institutional memory to his advantage, as he had been part of the ministry for many years before he left the civil service during the Esap job cuts in the early nineties, and he had also worked closely with Rtd Brigadier Agrippa Mutambara on the initial attempt to launch the NYS.

The other colleague had left the civil service for the same reasons and at the same time, but he had been with the Local Government Ministry.

He was an ideological fellow, an expert in commissariat work, having played a key role in developing teaching and learning materials for orientation lessons in Maputo during the liberation struggle.

Both colleagues were war veterans.

Initially we signed casual contracts with the ministry, not the Public Service Commission. The reason for that was that the PSC did not have any positions for our roles within the Ministry’s authorised official establishment. The position changed later in 2001 and we finally got added to the PSC establishment; but there were still serious problems. I will explain. We could only be accommodated at entry level.

I was responsible for the Administration and Human Resources aspect of the programme, the other colleague was the Procurement and Logistics Officer, while the third colleague with commissariat experience was responsible for NYS Training. However, I was given the additional role of developing the training materials, designing the NYS certificate, and so on. I was effectively the de-facto overseer of the three roles put together, a team leader of some sort.

As already indicated, the problem was that the PSC could only employ us at the entry level of administrative officer, and we were supposed to wait for two years to become senior administrative officers, and for another two years to become principal administrative officers, after which we would be eligible for promotional grades like deputy director, under-secretary and so on. We felt this was unfair. We were more than mere graduate entries we felt, and the ministry concurred.

Our actual roles demanded far higher responsibilities than our official positions, and as such the ministry had to top our salaries through an allowance.

We had endless meetings and lobbying to have this changed by the PSC, but nothing really ever changed up to the time I left in 2004. The ordeal was frustrating.

When we set up the first NYS Centre at Mount Darwin, the Mashonaland Central Provincial Ministry assigned an officer who was already under the PSC establishment to be the NYS liaison officer linking the Border Gezi NYS Centre to the mainline ministry administration in the Mashonaland Central Province. Ordinarily, this person was referred to as the principal provincial youth officer, responsible for all of the youth development

The training centre needed a training centre administrator, later to be called commandant, it needed trainers, later to be called instructors, it needed support staff, it needed boarding services staff like cooks, cleaners, janitors etc. There were serious disagreements over titles like commandant and even instructors. Eventually the terms were just used interchangeably, depending on who was using them and their background.

There was simply no PSC establishment for all the staff at the NYS training centres. Throughout September to December in 2001, I had to drive to Border Gezi Training Centre to manually pay staff salaries in cash at the end of each month.

The pays could not be processed through the Salary Services Bureau because none of the staff was on PSC books. The ministry employed them as casual employees.

The only other casual employees the ministry ever had were a few seasonal workers at vocational training centres, who were also paid in cash by the centre managers.

After the opening of Guyu in Matabeleland South, Dadaya in the Midlands, and other NYS Centres; we finally settled for an internal payment system where salaries were deposited into staff bank accounts from head office. By that time head office had expanded significantly, with support officers helping out with many roles.

All but the deputy director and the three of us were not on the PSC establishment, except for two or three officers that had been seconded to us by the provincial offices.

This effectively means that the NYS operated for its entire duration with the majority of its staff not recognised by the PSC establishment.

While the casual employees facility legitimised the legality of staff status, it was next to impossible to make budget bids for treasury.

Each year such attempts would be turned down.

We were always reminded to first go and sort out our establishment issues with the PSC before we could bid for staff salaries and all other related costs.

That was the bureaucratic quagmire we all got caught up in, and was never really resolved.

So how was the NYS program funded?

There was this very popular financial term called “virement”, essentially the process of transferring items from one financial account to another.

The ministry’s finance director had to virement our way out, raiding other accounts of the ministry to keep the programme going. It was only in 2003 that Treasury began to acknowledge the de facto legitimacy of the NYS bids.

Without an enabling Act and without an establishment from the PSC, Treasury grudgingly agreed to allocate some money to the program, mainly because the Auditor-General was not impressed with the idea of virements, and also the departments whose accounts were raided were failing to account for expenditure throughout the year. It is hard to account for money you never used.

For lack of space I will briefly address the issue of how NYS trainees were recruited. Essentially, it was a quota system where all the 10 administrative provinces were equally allocated trainee places.

So we started with Border Gezi Training Centre in Darwin, for example, and each province was allocated 100 places at the centre. The centre had a capacity of 1 000 trainees.

The provincial offices would then delegate recruitment to district offices, depending on the number of districts in the province.

If a province had five district offices for example, each of the districts would be asked to recruit 20 youths for the programme.

The age specification was 18 to 30. Priority was supposed to be given to youths with at least 5 “O” Level passes. Gender representation was 50:50 male and female.

Given the assurance for employment after NYS training competition became stiff. Head office staff sometimes directed district officers across the country to include Harare youths in their quotas, bribing cases were reported, and so on and so forth. Powerful politicians also brought in their own youths to be accommodated in the quotas, and as such many deserving youths with no connections could not make it into the program.

I had names given to me by very powerful and influential people and all they often said was. “I leave it with you to see how these youths can join the program.”

The director did it on his own behalf and also on behalf of others who had asked him for favours, his deputy did too, the permanent secretary did, and even the minister did it, and other directors, permanent secretaries and ministers as well.

So I would pass on the names to provincial directors with the same quoted instruction. They would also pass on the names to the district, with the same instructions. So the cycle went.

I will end with the placement desk, my sole responsibility until the time the role became so busy that I had to get an assistant in the form of one Mr Kunaka, seconded to Head Office by the Mashonaland East Provincial Office — a very nice gentleman.

After training all NYS graduates were supposed to go back to their provinces and do some form of community service for two weeks. This included helping the elderly with their harvests and other such related work, cleaning city streets, or working on government farms like those of the Prison Services Commission. This is how NYS graduates ended up manning queues in Harare and Bulawayo during the sugar and fuel shortages.

There were reports of abuse of the community service program, including by new farmers who thought the graduates were an easy source of free farm labour, politicians who thought they were ready campaign tools, and some NYS graduates themselves who were reported to be taking advantage of the program to their economic advantage, or just to exercise power for the sake of it.

Anyway, after the community service program all NYS students had to go to their district offices to register their qualifications and where they preferred to be placed for employment, small businesses or tertiary education.

My responsibility was to deal with the lists and place graduates accordingly. Some were placed with the Zimbabwe Defence Forces, the Zimbabwe Republic Police, the Zimbabwe Prison Services; line Government Ministries, Zupco, Zesa, NRZ, and also the NYS centres themselves, manly as support staff.

Those NYS graduates who wanted to go for tertiary education would be placed into Teachers Colleges, Polytechnics, Technical Colleges, Nursing Schools, the Judicial School, the School of Music and other such tertiary training institutions.

If the recruitment process had problems with interference and corruption, one can only imagine what we had to endure at the Placement Desk. I am not a corruptible character, but we had to put up with people who thought the NYS could enable an unqualified “O” Level graduate to enrol for teaching or nursing, or any other of the occupations.

We had many challenges, but we did the best we could to place people where they belonged, nurses to the nursing schools, cleaners to the cleaning places, cooks to the cooking places, soldiers to the barracks, clerks to the registry offices, grounds people to the grounds, and so on and so forth.

I am hopeful that these NYS article series I have done in the past three weeks have cleared some air on the noble but vilified NYS program.

If anymore questions would require any further clarification I will in the future do another piece on the NYS.

I thank you all.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

- REASON WAFAWAROVA is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia

Comments