‘At least he didn’t surrender to the enemy’

Tichaona Zindoga Senior Features Writer

IF one were to apply the literal sense of the adage that cowards die many times before their deaths, the cowardly William “Cde Disaster” Bonga who spent eight years, from 1978 to 1986, hiding from the liberation war, must have died many times before being discovered in a cave in Chipinge.

Only his death came much later.

A visit by The Herald over the weekend confirmed the worst that Cde Bonga feared many times over: the man died in November 2004 after some illness.

He was 53.

For those who may not be familiar with the story, Cde Disaster left his wife and a three-year-old son to join the liberation struggle in 1976.

He entered Mozambique through the Sango Border area and from there he and a number of other eager recruits were transported to a place called Xai and then to Chimoio for military training under the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army, Zanla.

He also said he received further training in Tanzania before returning to Zimbabwe in 1978 and operating from the Eastern Highlands under the Chimurenga name Cde Disaster.

One day, while carrying out reconnaissance in the “Tanganda area” there was a very heavy storm during an ambush.

When the group temporarily dispersed, that was the last he saw of his comrades. How he lost contact and his weapons is a complete mystery.

Cde Disaster wandered in the thickly forested mountains until he came to a cave, which was to be his home for eight years from late 1978 to November 1986.

He survived on wild fruit and stream water.

Even if he had had the means, he would not have lit a fire in all those years to avoid detection.

Emerging only late at night, Cde Disaster never met a single soul and kept extremely quiet all the time until he was smoked out of the cave by some village boys who were pursuing a rock-rabbit that ran into his cave.

Villagers then handed him over to the police, who in turn contacted the army.

He was taken to Mutare for vetting before he was transferred to Harare for further vetting by Zanu-PF officials.

Although the ruling party believed his story, Cde Disaster never received the $4 000 demobilisation payment given to ex-fighters who were not absorbed into the national army soon after independence in 1980 since the money had run out.

He however, got the $50 000 gratuity that was given to war veterans in the late 90s.

He lived quietly in Chiredzi where our news crew, this week, traced him only to learn he had passed on 10 years ago.

Mr Brown Bonga (68), Cde Disaster’s brother, confirmed the demise of his lily livered brother in his home area of Pfumari Village near Chikombedzi Growth Point in Chiredzi District.

“He was ill for some time — I do not know what his exact ailment was — but his belly and groin swelled and he went to seek help at Chiredzi Hospital but he didn’t improve. He later died at the nearby Chikombedzi Hospital,” said Mr Bonga.

It is said Cde Disaster was buried the morning after the night he died, without much ceremony and without a coffin.

He is survived by three children; the first born Andrew whom he left aged three-years-old when he went to the bush in 1976 and two others from two different marriages.

Another marriage did not produce any children.

Andrew’s mother is late while Cde Disaster’s last wife, whom he married in 2003, went to South Africa soon after his demise.

The elder Bonga described his relationship with Cde Disaster as warm but said the soldier was at times too quiet and enigmatic — like all ex-combatants, he said. They had welcomed him back from the war with ceremony.

“We were very happy when he came back because we thought he was long dead,” he said.

“I came from Bulawayo were I was working and we slaughtered a beast and bought beer to welcome him.”

Cde Disaster immediately settled down.

“When he came back he took up a job at the District Development Fund where he worked in the roads. After retiring in 1995, he came back to settle in the village,” said Mr Bonga.

Cde Disaster was a moderate drinker and fairly successful in farming, said his brother, although he admits he did not spend much time with him.

He also was not able to glean much from Cde Disaster how the soldier survived the elements in the temperamental climes of the Eastern Highlands

Was Cde Disaster a coward? The older Bonga laughs; holds back; smiles.

“Yes, he was,” he finally agrees, “he should have come out.”

Yet outside, during political rallies before his demise, Cde Disaster would pull some war routines and antics.

“He was well-known for that,” says Mr Bonga.

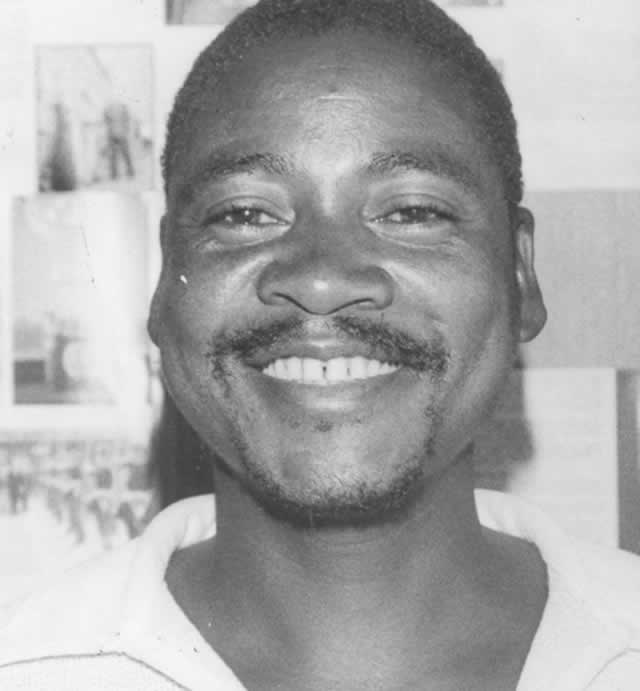

Cde Disaster’s son, Andrew (41), who is now a welder at Chikombedzi Growth Point, looks every inch the grinning old block of the pictures and he is as reserved and cryptic.

He grew up in the family where his mother, thinking that Cde Disaster had died, remarried.

Andrew is better known by his stepfather’s surname of Mbiza.

He grew up with the shame and stigma of his father’s curious tale, although he seems to have outgrown it. Nor does he hold a particular bitterness.

In fact, he does not believe his father was culpable at all for his fate.

“People used to mock me, especially in the first days, but you know you develop a thick skin,” he said.

“As a matter of fact I do not think my father stayed that long out of cowardice.

“After he came back we would go to some places and he would not show any cowardice. His ordeal was to do with evil spirits,” he said.

He then recounts that just before Cde Disaster came back, there were some rituals that were performed to cleanse the family.

“After that was done, the n’anga said, ‘Even this one that you say is long dead is not; he is going to come back’. My father came back after a while,” he said.

This narrative is not well corroborated.

But the local war veterans branch, although it did not honour Cde Disaster, spoke well of Cde Disaster.

“He was not a coward because he did not surrender to the enemy,” said Retired captain Hassan Chauke, a member of the Chiredzi district war veterans association and Ward 11 councillor.

“Even when he lost his weapon, he still managed to survive. I think it was not his problem but his illiteracy and failure to navigate the geography. If it were some of us who had gone to school we would have found a way,” he explained.

Chauke stated that he personally knew Cde Disaster and that they crossed into Mozambique together for training, arriving at Shaishai and then going to Chimoio.

They went separate ways after the bombardment at Chimoio in 1976, with Chauke going to Tete Province while Disaster went to Ethiopia for further training (Chauke’s account).

Another local and war vet, John Kayela Mbiza, claimed that the reason they did not honour Cde Disaster on his death was because the family had not communicated.

“That is one of the problems we are facing as war vets as families do not notify us so that we make presentations to authorities for relevant assistance,” he said.

It is not clear what honour would have been bestowed on Cde Disaster, whose story does not, up to now read for a glorious soldier.

But for his son Andrew, he even left one life lesson, which the younger Bonga remembers: “He told me not to pick up fights lest you lose friends.”

Comments