A precarious moment for Africa

Curtis Doebbler Correspondent

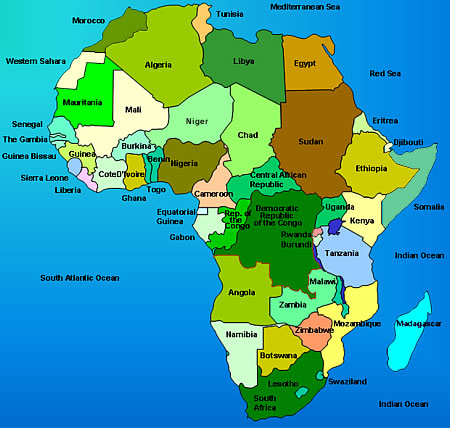

The upcoming meeting of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights taking place in Banjul, Gambia could be an opportunity for African states and civil society to stand-up for their rights regarding the threat of climate change. Over the past year, international diplomats have been busy trying to shape an international order that will disadvantage Africans for the coming decades. As a consequence the international framework being put into place may be deadly for generations of Africans. These unfortunate diplomatic maneuvers are being taken at several levels and most apparently within the world’s global body of the United Nations.

Moreover, these initiatives almost always come from developing countries. Disturbingly African diplomats seemed to be powerless to prevent the damage.

Perhaps the most potent damage is being done in the global climate change talks. While the time to take effective international action ticks past the hour of no-return, developed countries continue to balk on taking adequate action to address the consequences of climate change.

Global climate action is perhaps most important because the world faces a scientific imperative of either taking adequate action or seeing, as G77 coordinator Lamumba Daping warned a half decade ago, a hundred million Africans perish during the 21st Century due to the adverse effects of climate change.

Given this deadly imperative, developed countries are seeking to use it as leverage against developing countries to effectively replace the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) that they agreed to more than twenty-years ago with language reflecting common obligations for all states in the new climate agreement to be finalised in Paris this December.

This is being done with double-speak. Developed countries say they are not seeking to deny CBDR, but at the same time they are refusing to act in accordance with it. The inaction of developed countries is reflected in their refusing to undertake obligations that are adequate to address climate change.

As the adverse consequences of climate change will most significantly effect developing countries, particularly African countries and some low-lying island states, the result is that these states are left to choose between their development and their survival.

Already, based on estimates that developed countries provided at the Copenhagen Climate Summit in 2009, the bulk of the greenhouse gas emissions cuts are being left for developing countries to undertake. This reality seems confirmed by the Individually Determined National Contributions or INDCs that a few developed countries have submitted to date, which are once again voluntary statements about how much greenhouse gas emissions they will eliminate.

Essentially developed countries are saying to developing countries: “We benefited for centuries and we are unwilling to share the advantages we gained. You are own your own.”

In those instances when developing countries have dared to stand up to such actions because they are inconsistent with the terms of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, they have been battered down by back-room political dealings that apparently mix threats with short-term incentives.

The Philippines apparently bowed to US pressure to remove its most committed and competent negotiators. Bangladesh and the Maldives became silent after the Nassen initiative and the Climate Vulnerability Forum directed what appear to ‘hush’ money their way.

And in Sudan the articulate Ambassador Daping was taken out of the picture when the country was divided in two, another victim of US interference that prioritises the disorder of member states.

Elsewhere in the United Nations’ General Assembly debate concerning the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) developed countries are trying to put the emphasis on limiting the transfer of funds from North to South by imposing overbearing monitoring and verification requirements while refusing to accept the same control of their obligations to cooperate with developing countries.

In fact, to date the biggest problem has been the failure of developed countries to provide the financial assistance, access to technology and affordable capacity building that they have pledged to developing countries. Only a handful of the forty-plus states that pledged to commit 1 percent and later 0.07 percent of their GDP to overseas development assistance have ever achieved that goal and less than a handful are achieving it today.

In drafting the SDGs, which are intended to guide the post-2015 Development Agenda, despite a consensus agreement on a set of 17 goals, some developed countries — and only developed countries — are attempting to reopen the goals.

One reason for doing this appears clearly to be to weaken the special position of developing countries and to enhance the ability of developed countries to limit their own obligations based on conditionality.

While developing countries have fought off this challenge to date there are indications that their resistance is waning under the pressure of the United States, Europe and their allies.

Third, developed countries increasingly appear to be intensifying their attack on developing countries at the United Nations Human Rights Council.

To do this they have manipulated the forty-seven state entity based in Geneva, Switzerland to ensure that developed countries interests are prioritised despite the fact that developing countries technically outnumber developed countries by about a two to one margin. — Counterpunch.

Comments