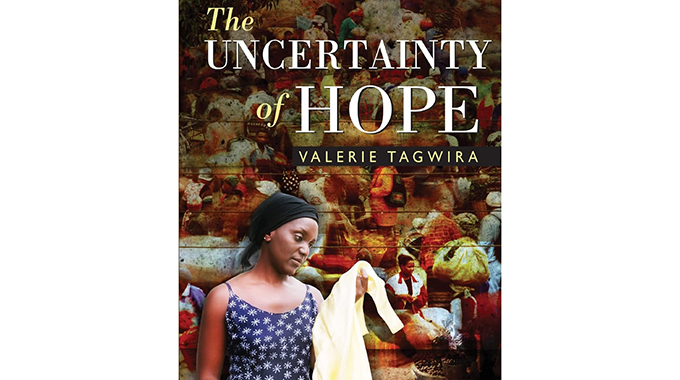

When hope becomes an uncertain dream

Elliot Ziwira At the Bookstore

In “The Uncertainty of Hope”, Valerie Tagwira uses realistic traits of modernism to highlight the nature of toil in the absence of hope, and the power of love in the face of lack and adversity.

The timeless book, published in 2006, gives reading a new meaning in view of expectation, unity of purpose and the uncertainty of outcomes in the gamble known as life.

True, reading is a reflection of one’s own experiences. An old story told with finesse of detail, as only a master storyteller can do, has a way of consuming the reader and hoisting him or her to another level in both place and time, where only he or she alone feels has ever been to.

Set in Harare, predominantly the high density suburb of Mbare in 2005, “The Uncertainty of Hope” visits the terrain of lack, frustration and the meandering queues of the period between 2002 and 2008, when darkness blighted the motherland’s prospects.

The use of realistic setting, fractured plot and apt characterisation takes the reader aback, as the story transcends individual travails to give meaning to shared experiences in which hope becomes an imperative ingredient in the recipe for positive outcomes.

As Chenjerai Hove maintains in “Palaver Finish” (2002), fiction is not fiction, but it is a collection of historical events that shape a people’s destiny.

There is no better way of capturing a people’s culture and history than through literature. It is so because the writer functions as a recorder of the mores and values of his or her people.

Through chronicling events using her experiences, Tagwira highlights the state of affairs that place the individual at odds with expectation. She pursues the story of Onai, a 36-year-old mother of three; 16-year-old Ruva, 15-year-old Rita and Fari, who is 10.

Like many in their Mbare neighbourhood, Onai’s family is poor. It is not because her husband is formally unemployed, like hordes of others in the ‘hood, but Gari, who is a section manager at Cola Drinks, is as gadabout as he is irresponsible, violent and callous.

Gari’s womanising nature alienates him from his family, much to the glee of the gloating Maya, and the irritation of Onai’s bosom friend, Katy.

Hardened by lack, cheered on by sorrow and checkered by hope, the protagonist provides for her family through vending at Mbare Musika.

She refuses to buckle to her friend’s exhortation that she should leave Gari and start a new life without him. Rather, she prefers her mother’s advice that culturally, a woman should remain in support of her husband, regardless of his shortcomings.

Like Shimmer Chinodya’s “Queues” (2003), “The Uncertainty of Hope” captures the neurosis, malaise and paralysis at the centre of the familial, communal and national platforms, as the individual suffers the bane of societal expectation in face of metaphorical and literal starvation.

However, unlike Chinodya, Tagwira uses the third person narrative technique, which gives the story a universal appeal.

Though she explores the nature of Man from the viewpoint of the marginalised, despite being a specialist obstetrician and gynaecologist, the writer gives snippets into the life of affluence through Faith’s relationship with the affable businessman and farmer, Tom, who is 35.

Also, unlike Chinodya, Tagwira examines the condition of womanhood, not through the eyes of an artist or a man, nor does she limit herself to the queues that permeate the lives of the realistic characters.

However, like Chinodya, she is aware of the claustrophobic nature of marriage, the burdensome nature of cultural expectation, the hypocritical inclinations of the rich and powerful, and the ‘bring her down syndrome’, which impedes women’s progress.

The resilient, forgiving, loving and rather naive Onai believes that her husband would miraculously change his spots and come back to his senses.

Knowing the reality of HIV/AIDS, she refuses to engage be intimate with her husband without protection.

As conversation eludes them, intimacy and peace desert them in equal measure.

The love that seems to be taboo in Onai’s marriage, finds shelter in her friend, Katy, and her husband, John’s abode. Like two peas in a pod, the friends are always at each other’s side, despite the setbacks.

Onai’s family is the definition of poverty, and her struggle out of it remains a losing battle.

With her ego battered at the home-front through violence, the protagonist’s inner turmoil reaches a tipping point as she learns of her husband’s affair with Gloria, a beautiful woman of loose morals, who is believed to be HIV-positive.

As the gods of hope conspire against Onai, and the lot of her ilk, Operation Murambatsvina cleans out the scum meant to be their livelihoods. Illegal shacks, market stalls, buildings and flea markets are razed to the ground. Also sutured, are their dreams.

Tagwira adeptly skirts around the political, social and economic landscapes that in most cases impose restrictions on vulnerable women and children.

As the HIV/AIDS pandemic takes root, the gloomy picture that ensues leaves a trail of hopelessness and despondency.

Reduced to meandering queues; queues for everything and anything, owing mainly to the illegal sanctions imposed on the country by the West, the motherland hopelessly seeks solace in hope.

As all this is playing out, Gari dies.

Gari’s death compounds Onai’s predicament. His brother, Toro, chases her and her children from their inherited home. Homeless, defeated and deflated the heroine takes trail into the unknown.

With her womanly pride high, she still believes that her dressmaking skills, Katy, the recently graduated lawyer, Faith (Katy’s daughter), her mother, the Kushinga group championed by progressive women like Emily, who is ironically Tom’s doctor-sister, would catapult her to the shimmering glow of hope etched somewhere at the periphery of her dreams.

Operation Garikayi, she hopes, would pedal her to sheltered hope.

Onai, like multitudes in her flock, is conscious of the symbolic importance of hope in life.

Nonetheless, she seems to be convinced that, “Hers was a life of guaranteed misfortune”, that even if she were to be offered something on a platter “something was sure to happen that would wrench the opportunity away from her.”

Such is the nature of life when hope is weakened. Could death be the only certainty in life? she wonders!

Comments