What do the Americans know about the Ebola outbreak?

Baffour’s Beefs with Baffour Ankomah

FROM the comforts of Southern Africa, the news of the “Ebola epidemic” in “West Africa” presents a scary situation. “Are you sure you want to go there? Are you not afraid of Ebola? What if you catch it?” These are some of the routine questions that my wife and I were bombarded with by concerned friends and acquaintances in Zimbabwe as we prepared for a holiday in Ghana in August.

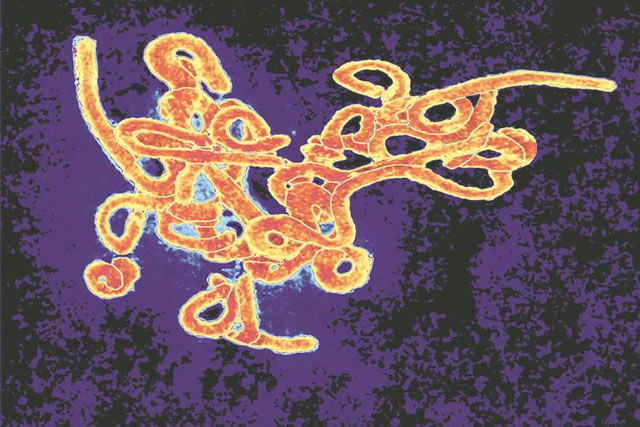

I kept telling them that the distance between Ghana and the nearest country to suffer from the current Ebola outbreak, Liberia, is about three hours flight away by the fastest jumbo jet. I am writing this column from Ghana, and not one case of Ebola has been reported in the country as I write, even though nearly 1 500 people have died in the “epidemic zone” of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia.

The anti-Ebola preparations in Ghana have been top-notch. Medical facilities have been readied in anticipation of the first case or cases. And public education on radio and TV has been consistent in telling people what to do if the Ebola Virus Disease (VCD) ever crosses the borders into the country.

I don’t blame the Zimbabweans or the other Southern Africans who think that as soon as you touch the soil of Ghana, Ebola will be lurking at the next corner waiting for you. That is not the case.

The reporting of the current Ebola outbreak by the Western media and their dutiful followers in the African media has been very, very poor, because it has been rid of context, to the point where people who haven’t been to “West Africa” before genuinely think that all West Africans are at risk. No, that is not the case.

In fact, the use of the generic term “West Africa” in the reporting is wrong, as “West Africa” is made up of 16 countries; and if three of them are hit by the current outbreak, it is disingenuous to tar the whole 16 countries with the same brush and make it look as if the whole 16 countries are in the throes of the epidemic.

If three of the European Union’s 27 member countries are hit by an epidemic, it will not be reported as a European epidemic. It will be regarded as local to the three affected countries, and their names will always be mentioned. Why the same cannot be extended to the outbreak in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, is a problem in the heads of the correspondents covering the story.

A bit of geography will do

Equally, the reporting has not explained that the epicentre of the current outbreak straddles the point where the borders of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia meet. This point is known locally as the Parrot’s Beak on account of how it looks on the map drawn by the Europeans at the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, during the era of the Scramble for Africa; and this area is only divided by a river or two.

In effect, it is the same local area slashed up, divided, compressed, and forced into three countries by the damned Europeans who sat at that conference in Berlin and shared the continent of Africa among themselves.

Like everywhere else in Africa that suffered from the pencil and ruler of the Europeans, extended families were divided and forced into two or three countries while still living in the same villages and towns before the pencil and ruler were applied.

As such, if epidemics like the current Ebola disease happens, brothers and sisters only have to cross the river that the Europeans designated as the “international” border between them to attend the funeral of the brother who has fallen victim to the epidemic.

If they are unlucky to be infected by the virus, they will cross the river back into their homes in the “new” country or countries that the Europeans created for them. The “epidemic” will then be reported as having affected two or three countries, and in no time it will be a “West African” epidemic.

Context is important

In Zimbabwean terms, it is much like the area where the borders of Zambia, Namibia and Zimbabwe meet, or the Tongas who lived peaceably in that area until they were divided by the European borders.

If an epidemic hits the local area, and there is a bereavement on the right bank of the Zambezi River now called Zambia, the Tongas on the left bank now called Zimbabwe will only have to cross the river to attend the funeral of their departed loved ones and cross back into Zimbabwe after the funeral.

In no time the epidemic will be reported as affecting two or three countries, but the reporting will not say that it is the same local area divided into two or three countries.

If the reporting then goes on to call it a “Southern African epidemic” and scares people from visiting Swaziland and Lesotho because of this epidemic, it will be a gross exaggeration and an injustice to the people of Southern Africa. This is what confronts West Africans today.

Apart from one passenger from Liberia who collapsed at the Lagos Airport and later died in hospital from Ebola, the current “epidemic” has been largely local to the local area straddling the borders of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia.

As such, next-door neighbours like Cote d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Mali and Senegal have not been touched at all. To think that countries farther away from the epicentre, like Ghana, Togo, Nigeria, Niger, etc, cannot be visited because they are in West Africa, is the height of ignorance.

There was an Ebola outbreak in Uganda in mid-2012. And nobody suggested that Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan and DRCongo -near neighbours of Uganda’s – or East Africa as a whole, should not be visited. So why is it different in West Africa?

Moreover, Uganda’s outbreak did not affect the East African region, it remained local to Uganda. In fact, Ebola has the characteristic of being local if it is diagnosed early and quarantined. The previous outbreaks in DR Congo and Sudan remained local to the two countries. Why West Africa is being treated differently this time beggars belief.

The American connection

In all this, the real story that has gone unreported is the American involvement in what has now become the epicentre of the so-called West African epidemic.

Before the current outbreak, American scientists had been doing research on haemorrhagic fevers, including Lassa and Ebola, in the very countries now affected by the current outbreak – Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Did the research go wrong? Did the researchers use the local area as a laboratory for their experiments? What happened exactly? These are questions the Americans have to answer. And immediately!

But not surprisingly, the Americans would not say more than telling their citizens that Ebola can only be contracted by touching a person who has already been infected with, or died from, the disease.

That “human to human transmission is only achieved by physical contact with a person who is acutely and gravely ill from the Ebola virus, or their body fluids” and that such transmission “is almost exclusively among caregiver family members, or health care workers tending the very ill”.

According to the Americans: “If you are walking around, you are not infectious to others. You cannot contract Ebola by handling money, buying local bread or swimming in a pool. There is no medical reason to stop flights, close borders, restrict travel or close embassies, businesses, or schools . . . You will not contract Ebola if you do not touch a person dying from Ebola.”

But the Americans would not say that long before the current outbreak, their scientists had been doing research into Ebola and other haemorrhagic fevers in the very three countries now in the throes of the current epidemic.

American interest in infectious diseases

Weeks before the current outbreak, Curtis Abraham, the correspondent of the London-based New African magazine, had reported that “the US government has stepped up interest in infectious diseases such as the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) because of their potential use as a weapon of mass destruction by terrorist organisations, state-sponsored actors, and simply deranged individuals.

“EVD is classified by the US Centres for Disease Control (CDC) as a Category A bioterrorism agent.”

According to Abraham: “Biomedical researchers working for the US Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) and partly funded by the US Department of Defence’s Joint Project Manager Transformational Medical Technologies (JPM-TMT), have been developing preventative and curative drugs to combat any possible bioterror threat from EVD and other viruses.

“However, despite lobbying from scientists before the latest outbreak, the drugs have not been put to the test. One leading candidate is TKM Ebola, an anti-Ebola viral therapeutic, developed by the Canadian pharmaceutical company, Tekmira, under a contract with JPM-TMT.

“TKM-Ebola has shown a 100 percent success rate in monkeys. Back in mid-January 2014, Tekmira announced that it had dosed the first subject in a Phase One human clinical trial of TKM-Ebola. The study was meant to evaluate the safety, determination of a safe dosage range, and identify any possible side effects as TKM-Ebola is absorbed in the body of healthy adult subjects.”

Abraham continued: “In March 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration granted TKM Ebola fast track status to speed up its development.

“Dr Ian MacLachlan, Tekmira’s chief technical officer, announced in a paper presented at the 17th meeting of the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy in Washington DC, that the company had successfully completed the single ascending dose portion of the TKM-Ebola Phase One clinical trial in healthy human volunteers and that there were no ill effects.

“Tekmira expects to complete the Phase One clinical study later this year. Some scientists see the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa as a unique opportunity to greatly advance the search for a cure, and the vaccine is being stockpiled by the World Health Organisation (WHO) for use in emergencies.”

In June this year, the WHO allowed TKM-Ebola to be used on victims of the outbreak in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia.

In his story, Curtis Abraham quoted Dirk Haussecker, a biologist and medical consultant, as having said: “The primary objective of employing TKM-Ebola would be to further the clinical development of this agent.

“This outbreak is the best-case scenario to test this agent in actually infected patients with a side effect being that it would provide an incentive to people to be isolated.”

According to Abraham, TKM-Ebola is not the only promising drug on the horizon. Several groups of biomedical researchers have already identified 150 or so neutralising antibodies against the Zaire strain of the virus, the strain responsible for the current outbreak.

“Some of these anti-Ebola virus antibodies have been used in cocktails and successfully administered to non-human primates. The monkeys survived in spite of being given lethal doses of EVD two days prior to being fed the cocktail.”

Africans with long memories remember that in the past strange disease outbreaks like Ebola and HIV-Aids have occurred in remote, forested parts of the continent when Western scientists have popped up in these areas or are conducting clinical trials of drugs.

Remember how Aids spread

One remembers the Aids epidemic and how it spread so fast throughout Africa in the 1980s and 90s, yet before 1980 when Aids was first discovered in homosexuals in San Franscisco, USA, Africa knew no Aids.

One school of thought actually holds the belief that HIV-Aids was a US biological warfare experiment went awry, as in 1970 the Congressional Appropriations Committee had sanctioned a 10-year, $10m research into the production of “an organism that does not naturally exist but which will affect the immune system” for use as part of the US germ warfare programme.

The 10 years coincided exactly with the discovery of HIV-Aids in gays in San Francisco. At the time, the disease was called Gay Related Immune Disease (GRID). Years later, with gays protesting, the name changed to HIV-Aids, with the blessing of the American and French governments whose nationals claimed to have jointly discovered the HIV virus.

Later, an unsuspecting and weak-headed Africa became the origin of the HIV virus because the Westerners said so. And the Africans said Amen.

As in the times past, the template has not changed. US scientists, both government and privately funded, are notorious for using unsuspecting human beings, mostly African-Americans, as guinea pigs for the development and testing of germ warfare agents. Or of rushing in with untested drugs to emergency areas such as the current outbreak of Ebola, to test those drugs on victims.

This has lead many Africans to think that these scientists deliberately enter remote areas of Africa, insert the viruses, and then capitalise on the subsequent epidemics to test their drugs. As Dr Julius Lutwama of Uganda’s Virus Research Institute puts it: “My conviction is that if I am on my death bed and there is something that might alleviate my quick death in a condition where nothing conventional is approved, I would go for what is available.”

Precisely. That is why concerned Africans are calling on the US government to come clean on the current outbreak of Ebola in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia and tell the world what its scientists knew about the outbreak.

The voices of these concerned Africans have been strengthened by a report written by Jon Rappoport of Global Research, and published by WordPress.com on August 2 this year.

American whodunit?

In the report, Rappoport called for “an immediate, thorough, and independent investigation of Tulane University [USA] researchers and their Fort Detrick associates in the US bio-warfare research community, who have been operating in West Africa during the past several years. What exactly have they been doing? Exactly what diagnostic tests have they been performing on citizens of Sierra Leone?”

Rappoport continued: “Why do we have reports that the Sierra Leone government has recently told the Tulane researchers to stop this testing? Have the Tulane researchers and their associates attempted any experimental treatments (e.g., injecting monoclonal antibodies) using citizens of the region? If so, what adverse events have occurred?”

Rappoport revealed that “the research programme, occurring in Sierra Leone, the Republic of Guinea, and Liberia – the epicentre of the 2014 Ebola outbreak – has the announced purpose, among others, of detecting the future use of fever-viruses as bio-weapons. Is this purely defensive research? Or as we have seen in the past, is this research being covertly used to develop offensive bio-weapons?

“For the last several years, researchers from Tulane University have been active in the African areas [Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia] where Ebola [has] broken out in 2014. These researchers are working with other institutions, one of which is USAMRIID, the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, a well-known centre for bio-war research, located at Fort Detrick, Maryland.”

According to Rappoport: “In Sierra Leone, the Tulane group has been researching new diagnostic tests for haemorrhagic fevers. [Note: Lassa Fever, Ebola, and other labels are applied to a spectrum of illness that result in haemorrhaging].

“The Tulane researchers have also been investigating the use of monoclonal antibodies as a treatment for these fevers – but not on-site in Africa, according to Tulane press releases.

“Here are excerpts from supporting documents. Tulane University, Oct. 12, 2012, ‘Dean’s Update on Lassa Fever Research’:

“In 2009, researchers received a five-year $7, 073,538 grant from the National Institute of Health to fund the continued development of detection kits for Lassa viral haemorrhagic fever.

“…Since that time, much has been done to study the disease. Dr. Robert Garry, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Dr. James Robinson, Professor of Pediatrics, have been involved in the research of Lassa fever.

“Together, the two have recently been able to create what are called human monoclonal antibodies … These antibodies have been tested on guinea pigs at The University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston and shown to help prevent them from dying of Lassa fever…

“Most recently, a new Lassa fever ward is being constructed in Sierra Leone, at the Kenema Government Hospital [one of the centres of the Ebola outbreak]. When finished, it will be better equipped to assist patients affected by the disease and will hopefully help to end the spread of it.”

—-Second document—–

Rappoport continued: “Here is another release from the Tulane University, this one dated Oct. 18, 2007: ‘New Test Moves Forward to Detect Bio-terrorism Threats’.

“The initial round of clinical testing has been completed for the first diagnostic test kits that will aid in bio-terrorism defence against a deadly viral disease. Tulane University researchers are collaborating in the project.

“Robert Garry, professor of Microbiology and Immunology at Tulane University, is [the] principal investigator in a federally-funded study to develop new tests for viral haemorrhagic fevers. Corgenix Medical Corp., a worldwide developer and marketer of diagnostic test kits, announced that the first test kits for detection of haemorrhagic fever have competed initial clinical testing in West Africa.

“The kits, developed under a $3.8 million grant awarded by the National Institutes of Health, involve work by Corgenix in collaboration with Tulane University, the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, BioFactura Inc, and Autoimmune Technologies.

“Clinical reports from the studies in Sierra Leone continue to show amazing results,” says Robert Garry, professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the Tulane University School of Medicine…

“We believe this remarkable collaboration will result in detection products that will truly have a meaningful impact on the healthcare in West Africa, but will also fill a badly needed gap in the bio-terrorism defence … The clinical studies are being conducted at the Mano River Union Lassa Fever Network in Sierra Leone.

“Tulane, under contract with the World Health Organisation, implements the program in the Mano River Union countries (Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea) to develop national and regional prevention and control strategies for Lassa fever and other important regional diseases …

“Clinical testing on the new recombinant technology demonstrates that our collaboration is working,” says Douglass Simpson, president of Corgenix.

“We have combined the skills of different parties, resulting in development of some remarkable test kits in a surprisingly short period of time. As a group, we intend to expand this program to address other important infectious agents with both clinical health issues and threat of bio-terrorism such as Ebola.”

—-Third document—-

According to Rappoport: “The third document is found on the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation Facebook page, dated July 23, 2014 at 1:35pm. It lays out emergency measures to be taken.

“We find this curious statement: ‘Tulane University to stop Ebola testing during the current Ebola outbreak.’ Why? Are the tests issuing false results? Are they frightening the population? Have Tulane researchers done something to endanger public health?

“In addition to an investigation of these matters, another probe needs to be launched into all vaccine campaigns in the Ebola Zone. For example, HPV vaccine programmes have been ongoing. Vials of vaccine must be tested to discover all ingredients. Additionally, it is well known that giving vaccines to people whose immune systems are already severely compromised is dangerous and deadly.”

A concerned Ghanaian

As the concerned Ghanaian journalist, the veteran Cameron Duodu, put it: “There are enough questions in Jon Rappoport’s article for the US health authorities to issue an immediate and truthful statement on what the Tulane University and its associates have been doing in the very region from which Ebola has broken out and is in danger of affecting many other countries.

“In the age of the Wikileaks and the Snowden leaks, it was remiss of the US government not to anticipate that the research being done in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia would be linked to the current Ebola outbreak, and issue a statement to avoid panicking the populations of those countries and their neighbours.

“The WHO must also tell the world what it knows about these tests in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia and explain why it has not made the world aware of them up till now! Is the WHO totally convinced that full ethical standards have been met by the Tulane scientists during this outbreak which the WHO has classified as an ‘emergency’?

Duodu went on: “After all, there is a wealth of evidence to demonstrate that it is not altogether fanciful to suggest HIV-Aids, for instance, was probably spread initially by infected homosexuals in the US, and was brought to Africa by scientists who wished to find a cure for it. The WHO’s role in HIV-Aids research has not been fully explained. We need answers from the US government and the WHO. Now!”

I, Baffour Ankomah, rest my case. We shall see if the Americans will open their mouths about what they know, and did, in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia before the current outbreak of Ebola.

Comments