War wasn’t for sissies: The story of Cde Disaster

Features Writer

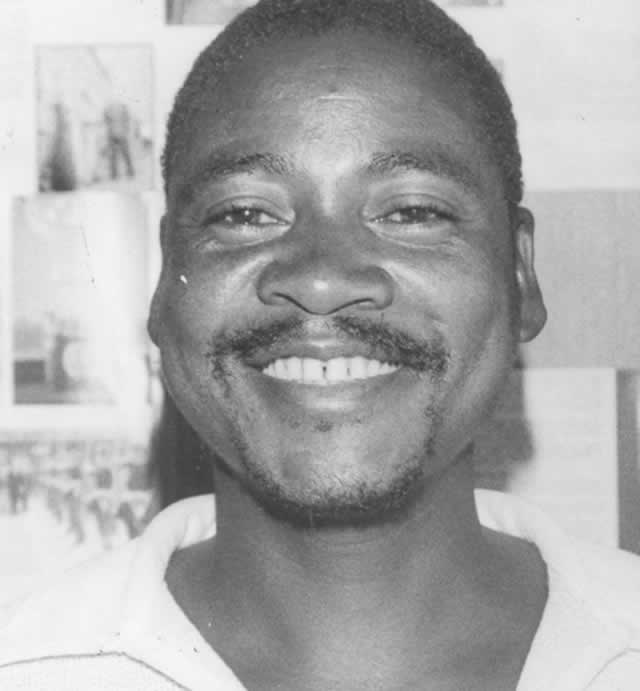

WHEN former freedom fighter William Jimu Bonga (48), popularly known as comrade Disaster, was discovered in a cave in 1986 — six years after independence — his incredible story was the talk of towns and country.

Many people found it hard to believe that the guerilla had hidden away for eight years after he lost his weapons in battles in northern Chipinge District.

Letters to the Press, as well as street talk, generally lashed out at him and he felt persecuted.

But 13 years down the line, the shy and soft-spoken man still maintains his extraordinary tale.

In a recent interview with The Herald at his Pfumari village home, 10km west of Chikombedzi Growth Point in Chiredzi District, Cde Disaster said he hid away in the mountains for all those years because he could not stand being captured and interrogated by the enemy.

“Since it was my first time in the area, I was afraid that people there would hand me over to the Rhodesian forces,” he said, recalling his trying years in Zimbabwe’s perennially chilly Eastern highlands.

“Without my gun I couldn’t stand being captured and interrogated. So I decided that it was better to die in the bush.”

Even today, he cannot give a clear account of how he lost both his gun and track of his colleagues.

All he remembers is that one day, while carrying out reconnaissance in the “Tanganda area” there was a very heavy storm during an ambush.

When the group temporarily dispersed that was the last he saw of his comrades. How he lost contact and his weapons is a complete mystery.

Cde Disaster wandered in the thickly forested mountains until he came to a cave, which was to be his home for eight years.

Bonga left his wife and a three-year-old son to join the liberation struggle in 1976.

He entered Mozambique through the Sango Border area and from there he and a number of other eager recruits were transported to a place called Xai and then to Chimoio for military training under the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army, Zanla.

He also said he received further training in Tanzania before returning to Zimbabwe in 1978 and operating from the Eastern Highlands under the Chimurenga name Cde Disaster.

“I thought the name was good. Everyone had a pseudonym (read nom de guerre),” he said with a shy smile.

Misfortune struck soon after entering the country when he lost his gun and track of the other comrades during an ambush.

From late 1978 to November 1986, Cde Disaster lived in a cave, surviving on wild fruit and stream water. Even if he had had the means, he would not have lit a fire in all those years to avoid detection. Emerging only late at night, Cde Disaster never met a single soul and kept extremely quiet all the time.

“One day a group of people who were hunting with dogs came across me in the cave and ordered me to come out, to which I obliged. They asked me a lot of questions and I explained my situation. I was shocked to learn that the war was over a long time ago,” he said.

News of the anxious and hectic months of disarmament and gathering at assembly points following the 1979 Lancaster House agreement and elections in March 1980 was astonishing to Cde Disaster.

The group of villagers then handed him over to the police, who in turn contacted the army.

A certain Captain Jumbo took him to Mutare where he was vetted.

From Mutare he was transferred to Harare for further vetting by Zanu-PF officials.

Although the ruling party believed his story, Cde Disaster never received the $4 000 demobilisation payment given to ex-fighters who were not absorbed into the national army soon after independence in 1980.

The demobilisation directorate informed him he had come late and that the funds had been exhausted after the government paid out nearly $116 million to more than 30 000 people.

Demobilised fighters also got $185 every month between 1981 and 1982.

But the public expressed mixed feelings about Cde Disaster’s predicament. While they were touched by his plight, many were merciless and attacked him for being an impostor.

Some of several readers’ letters to this newspaper partly read: “I am not satisfied with his story.” “I feel remorse for my dear friend Bonga Disaster.”

“If Disaster Bonga is truly a Zanla combatant, or if he had been trained by Zanla forces, he is termed a deserter and the military wing should impose some disciplinary action on this individual.” “How could anyone justify demob pay from our taxes to ‘fighter’ W J Bonga?” “…I think nearly everybody would like to learn more about his hiding which is quite hard to believe given that he does not really know when he lost his weapons.”

Bitter about the issue, Cde Disaster returned to his Chiredzi home, where he surprised his widowed mother and other villagers who had given up looking for him.

Everyone, including his wife who had already remarried in the area, thought he had died in the war.

He respected his wife’s decision to remarry, believing he was dead.

Cde Disaster then slowly began to rebuild a new life.

In 1987 he got a job with the District Development Fund as a casual worker, a job he faithfully kept until he retired last year.

He remarried in 1988 and was blessed with his second child, a girl now 10 years old in Grade Three at Pfumari Primary School. Some months after retiring, he earned his “50kg” — the $50 000 lump sum gratuity and $2 000 a month paid to all former freedom fighters.

“I stopped work because it was hard work shovelling, digging and maintaining the roads. It was backbreaking and painful work. I now just want to have a rest.

“Maybe if I had gone to school I could have had a better job. But I never went to school and only know a few things I learnt from my brothers.”

The last born in a family of 10 children, six of them female, Cde Disaster is not ashamed of his illiteracy.

“My parents never sent me to school because they could not afford it. I spent most of my youth and young adulthood herding cattle.”

Besides there being only two schools, Chikombedzi and Chanyenga, Cde Disaster said that in those days many children never went to school because of the long distances involved.

Out of employment, he now spends most of his time tilling his five acre field and looking after his mother and family.

His father died some time before he joined the armed struggle. Although he says the $50 000 and the monthly $2 000 have tremendously improved his life, Cde Disaster still tills his field by hand since he does not own any cattle.

His livestock includes chickens, which he said he has never counted, and six goats.

While things have generally improved from the days of colonial rule, Cde Disaster said several places such as his home area, are still underdeveloped.

He said: “I am glad we are now free but some of our areas are still underdeveloped in many aspects. Here in Chiredzi, for example, we still face a major problem of hunger although the area has very good soil,”

Situated in natural region five, Chiredzi is perennially dry and drought prone, with very little rainfall. The country’s sugar estates, located in the area, thrive on irrigation.

This year was an exception otherwise the area has been on the government drought relief registers for the past seven years.

The last rainfall season was unusually above average and many people expect good harvests. Cde Disaster has a healthy sorghum and maize crop.

While his home village now has its own primary school, children still travel long distances to Chikombedzi growth point to attend secondary school, and even further north into the interior of Masvingo province for ‘A’ Levels .

Cde Disaster is determined to educate his daughter to make up for his own lack of education.

Comments