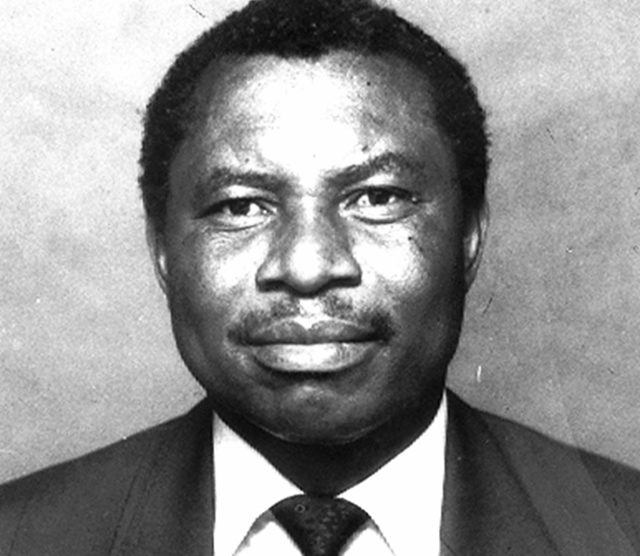

Tribute to Dr Muchena

Sifelani Tsiko Senior Writer

The death of Dr Samuel Muchena, eminent plant geneticist and the brains behind the dwarf maize hybrid, has robbed Zimbabwe and Africa of an exceptionally gifted person who was a driving force behind the quest for high performing and high impact seed varieties.Dr Muchena died last Friday at the age of 69 at Parirenyatwa Hospital where he was recovering after undergoing surgery for a brain tumour.

Complications arose after an accident in Harare few weeks ago.

Through his research, he helped to put Zimbabwe in the international limelight as a hub of scientific innovations.

Few will remember that Zimbabwe is one of the first few countries in the world to develop hybrid maize varieties.

Zimbabweans must take pride in their scientific reputation which led local agricultural experts to develop the SR52 maize hybrid as far back as the early 1950s, boosting production of one of the most planted crops in the country and the entire continent.

Some researchers even argue that Zimbabwe is the second country in the world, after the United States, to develop maize hybrid seed varieties that were tailor made to fit into the country’s environment characterised by marginal rainfall conditions.

And, Dr Muchena revelled in the opportunity for a breakthrough in maize genetics and a study he undertook with Dr Kingstone Mashingaidze and Kenneth Nyamarebvu in the late in 1980s led to the development of the Dwarf Ac31 and AC71 varieties which became popular among farmers.

In an interview with the writer way back in 2006, Dr Muchena showed his passion for science and took pride in the country’s scientific achievement.

“Zimbabwe was one of the first countries in the whole world to release hybrid maize on the market,” he said back then. “This is how we, Zimbabweans, came to be known as the breadbasket of the region. We have had that history of technological innovation which transformed agricultural production.”

But somehow, Zimbabwe later lost this status owing to radical changes in the agricultural sector. The need for equitable land distribution meant that land was soon to become a fiercely contested resource and the fight for this resource even spilled into the field of agricultural research.

Dr Muchena was carefully but sharply outspoken on issues of scientific structure and the need for Zimbabwe to embrace biotechnology to enhance its food security and solidify its national base of agricultural research.

“I feel strongly that we really need to find ways to restore our capabilities in this area of agricultural research and development,” he once said.

“We appreciate the efforts of the Government to promote agricultural research; but what has made things worse are poor salaries for staff, lack of working capital for researchers and the mass exodus of trained professionals to other countries.

“There is need for more investment and we probably need more partnerships with industry and international organisations wherever possible, otherwise our research, which has been one of Zimbabwe’s major achievements will slide backwards.

“We have to combat the brain drain and come up with innovative ways of recruiting and retaining skilled professionals as well as policies that promote research work in the country.”

At every forum that he attended, Dr Muchena never hesitated to talk about biotechnology and how failure to adopt the technology had made the country to lag in terms of understanding and harnessing the benefits of biotechnology.

He even warned that there was a danger that the country would lose its comparative advantage and end up importing even those maize varieties that it could produce on its own.

Dr Muchena’s enduring achievement in his career spanning close to four decades, was the development of the dwarf maize hybrid seed which out yielded conventional hybrid varieties by 40 percent under drought conditions.

He was passionate about the dwarf seed variety.

“Our idea was to modify the plant to fit well in environments where water and fertilisers are usually scarce and limit production,” he said in a 2006 interview. “Vice-versa, we wanted to find a variety that would, in good soils with good water and with adequate fertiliser, produce a good yield.”

The whole thrust, he said, was to come up with the short-statured maize hybrid varieties which were superior to their tall ‘‘counterparts’’ in terms of grain yield, drought and pest resistance as well as nutrient use efficiency.

In Swahili, they say: “Thatch water can fill the water pot,” meaning steadiness and patience can result in great success.

“My work started in the 1970s. I developed some of the ideas when I was studying for my PhD in Mexico in the early 1970s,” Dr Muchena said. “My research involved studying and comparing different maize varieties. Some were quite tall (as high as 3m) and some short (less than 2m).

“When I subjected these to water stress, I found out that the tall ones suffered most compared to the shorter ones. So I concluded that there was something in shortness which contributed to better performance and yields even under stress conditions.”

He also found out from other researchers that shorter plants also performed better under nutrient stress conditions with limited fertiliser.

Based on these findings, Dr Muchena designed a maize-breeding programme in Zimbabwe when he returned home in 1977 to work under the Department of Research and Specialists Services in the Ministry of Agriculture.

While studying in Mexico and at Uganda’s Makerere University, Dr Muchena managed to get materials, including the germ-plasm, which he was to use later in developing the dwarf maize varieties.

From the Department of Research and Specialist Services, he moved on to the University of Zimbabwe where he lectured crop science until 1988 when he was appointed as a deputy secretary in the Ministry of Agriculture responsible for technical services.

He served in the civil service until 1990 when he joined the African Centre for Fertiliser Development where he continue to work until his death.

“Using my knowledge of genetics, I simply shortened them and came up with the dwarfed variety using short plant genes. When I left the UZ in 1983, one of my students, Dr Kingstone Mashingaidze and technician Mr Kenneth Nyamarebvu, began to combine some of the parents we had developed and came up with the dwarfed maize variety hybrid which produced good yields,” he said.

“In our pilot tests, the plants produced big cobs even when they were short. It was an exciting development, but that still had some problems to be solved at that stage,” he added.

“They could not fit well into the husk, (so) we had to do more work to ensure that there was enough cover for the cobs. That was one of our major hurdles together with some diseases that the maize was susceptible to.”

After carrying out many trials to polish up the dwarf variety, Dr Muchena, in partnership with a private sector input and seed distribution firm, Agricura, launched the AC (African Centre) 31 and AC71 dwarf maize varieties in the 1988 — 1999 farming season.

This breed, which was designed to improve drought resistance and nutrient use efficiency in maize was well received by local farmers as well as their counterparts in Zambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, South Africa, Malawi and Botswana.

Dr Muchena’s path to science was far from ordinary and his passion for science was an inspiration to many of his friends, students and colleagues.

Despite his wealth of experience and various successes, he remained a very modest and approachable person. He was always supportive to young scientists and quick to praise success.

He sat on numerous boards and councils, among others the Research Council of Zimbabwe. Agriculture Research Council and the National Biotechnology Authority.

Dr Muchena was born in 1945 at Muchena village near Penhalonga in Manicaland. He went to several Zimbabwean schools ending at Goromonzi High School for his A levels.

After completing his A levels, he went to Makerere University where he obtained BSc and MSc degrees in agriculture. He studied for his PhD at Cornell University in New York and was attached to the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre in Mexico for seven years for the research that went into his thesis.

He is survived by his wife Rina and two children as well as six others from two previous marriages.

Dr Muchena separated from his wife, the Minister Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development, Olivia, in 1984.

He will be best remembered for his formidable brain power as plant breeder as well as for his scientific acumen and academic leadership.

Comments