They die, others are born

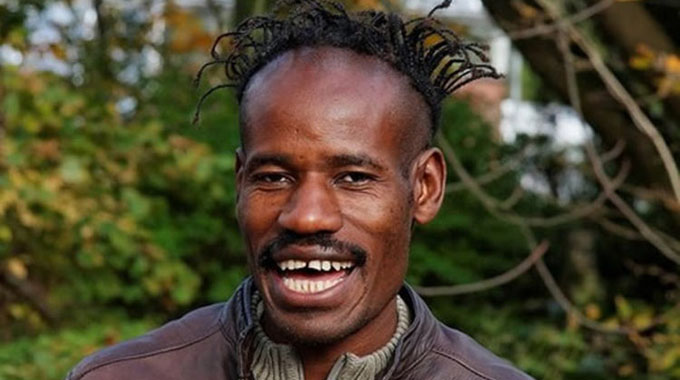

David Mungoshi Shelling the Nuts

People are likely to think me callous and uncaring, and even just a little conceited. When our people say, “They die and others are born” they are not being unsympathetic. All they are doing is to give the seasons their rightful place and recognition.

All things fit into some kind of pattern and logic. Nothing is for nothing and there is indeed a time and place for everything.

To a very large extent, this saying about baton-passing and baton-receiving is one of our least appreciated gems of wisdom.

Too many people think of death in one sense only, that of being stiff, silent and unfeeling.

For some reason, people tend to look at death as if it is a tragedy. The fact is death is life obeying its dictates. Just as the sinking sun winks and tells us that it is time for our daily dose of suspended animation, by the same token the red east at dawn brings in the early morning sun that reminds us of the daily grind.

In other words, we sleep because we must and we rise again in the morning because we must. We do these things as a matter of course. Those of us who do not, are rebels without a cause. Life makes you cross over in death.

Although Kahlil Gibran warns parents to never forget that the souls of their children “dwell in the house of tomorrow” which none can ever visit, even in their wildest dreams, he also says, “You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.”

So, when my child is born, she is the arrow that I shoot forth into the future.

She is my message to those yet to be born, to beings that will one day walk the surface of this earth as if no one else ever did.

When I was reading theology at university, a lecturer of ours (Mr Prozesky by name) told us a story about the devotional ingenuity of a certain Count Otto Von Zinzendorf, who loved God so much that he decided to write him a love letter.

After writing the love letter, he went to a window on the top floor of a very tall building.

With a flourish, the count threw the precious letter out into the blue sky. The idea was for the letter to somehow fall at heaven’s door. The lengths to which we go sometimes!

What is clear is that human beings yearn to leave their imprints on the avenues of time.

They long to send messages into the future. That is the rationale for art in all its forms. Rock paintings by early man on hillsides and in caves all over the world speak to this obsession as does all the work by the masters (Leonardo da Vinci, Van Gough, Picasso, Raphael and even our very own Dominic Benhura.

Songs and literature do the same. “Message in a Bottle” by Police is a song about a human being adrift on a sea of silent loneliness. The evocative lyrics of “Message in a Bottle” in part say:

Just a castaway

An island lost at sea

Another lonely day

With no one here but me

More loneliness

Than any man could bear

Rescue me before I fall into despair

I’ll send an SOS to the world

I’ll send an SOS to the world

I hope that someone gets my

Message in a bottle

The hope is that on some lucky day the bottle will be washed ashore and that its message would still be intact.

I have never been to prison except perhaps in a very symbolic sense and only very temporarily.

In September of 1964, with Zambia’s independence looming, I boarded a passenger train in Livingstone, eager to get back home to Bulawayo.

We crossed the bridge into Victoria Falls and as the train eased into the station, the white conductor wanted to see my ticket and my passport.

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland had recently been dissolved. We had all been one big country together and had needed no passport to travel across the length and breadth of the federation.

I had earlier on crossed from Southern Rhodesia without a passport into Northern Rhodesia, soon to become Zambia, on becoming a Republic in October of 1964.

I was hauled off the train with my trunk and taken to the police station where I was locked inside a dark cell and left there until noon on the next day.

They fed me on something terrible. Sitting there in the smelly cell, I saw that some people had scratched their names on the dirty walls. Desperate things like “John Moyo was here.”

I was tempted to etch my name on the violated wall, but decided against it. Later, they made me remove my shoes and sat me down on the cold floor of the charge office. After some interrogation, they let me go and I made my weary way back to the railway station to wait for that evening’s train to Bulawayo.

Once back at base, I found captive audiences and regaled them with embellished stories about all my experiences in Zambia: the drives to the game park, the smell of fish in Livingstone’s Maramba African Township.

I spoke proudly about attending a political rally in Maramba where Sikota Wina was addressing a crowd.

Sikota was one of the two Wina brothers in Government.

The older and more gentlemanly was Arthur Wina.

Both brothers were ministers in several of KK’s cabinets between 1964 and 1991 before UNIP (United National Independence Party) lost out to the MMD (Movement for Multi-Party Democracy).

The urbane Arthur Wina served as Minister of Finance in one of the UNIP cabinets. Those were the heady days of “One Zambia, One Nation” and Kenneth Kaunda’s humanism. But the old order gave way to a new one.

In later years, Dennis Liwewe was doing wonders as a football commentator on Radio Zambia.

Not many Zimbabweans knew Liwewe until after Independence. Some of us remember that match at Lusaka’s Independence Stadium, when the Warriors outshone Chipolopolo before thousands of spectators.

Liwewe’s voice rang out enthusiastically, “Here they come again, wave after wave of deadly attacks. That man Shacky Tauro, what a player! And on the stands, thousands of Zimbabweans resident here in Zambia, their second home – cheering their compatriots. Byron Emmanuel, it’s a goal!”

Evans Mambara took on the mantle from Liwewe in Zimbabwe.

Recently, I happened to meet an old-time football player from the golden days of Black Aces, a team with a rock-solid defence marshalled by Big Daniel Chikanda, popularly known as The Rock of Gibraltar.

This footballer from bygone days had captivating memories about soccer in his days.

Surprisingly, he was still in football, but now only as a coach. He sounded excited and overwhelmed that an obscure team called Nichrut from the Midlands town of Shurugwi had made it into Zimbabwe’s top flight football division.

The unspoken words were that he too would make it one day soon.

Once or twice as we shared a bench in a pharmacy and spoke animatedly about the gifted players from yesteryear, I saw him shake his head wistfully.

He must have been thinking about the things he could no longer do.

The words of the mbira song by Zimbabwe’s “Mhuri YekwaRwizi” with John Hakurotwi Mude on lead vocals singing, “Handicharugoni ndachembera” (I’ve grown old somehow; I can’t do it anymore) came into my mind.

What a drag that must be, having to inevitably bow to your imposed limitations. A hard man from a rival team broke his leg with a crunch tackle and that ended any further interest he might have had in the match.

Naturally, the coaches found someone to play his role.

Gary Glitter was once in hospital with a throat ailment that needed surgery.

This was at the height of his glittering career. The surgery was a delicate one and there was a possibility that he could lose his voice.

Distraught with worry, he threatened to shoot himself if that happened.

Hakurotwi Mude’s song talks about letting go of those things that we can no longer control.

In other words, we must die to some of these things.

We must pass on the baton and accept that other people can and will do just as well as we are likely to ever have done in our time.

When it is their world, we should allow them to be supreme. In time they too will be superseded by others.

As our stars wane, the stars of other people light up.

That is one sense in which people die and others are born to replace them.

And while the future is important and we all should play our part in shaping it, we must, nevertheless, allow those that dwell in the house of tomorrow to have a say in their lives.

David Mungoshi is a writer, social commentator and editor.

Comments