The Ian Smith myth and other fallacies

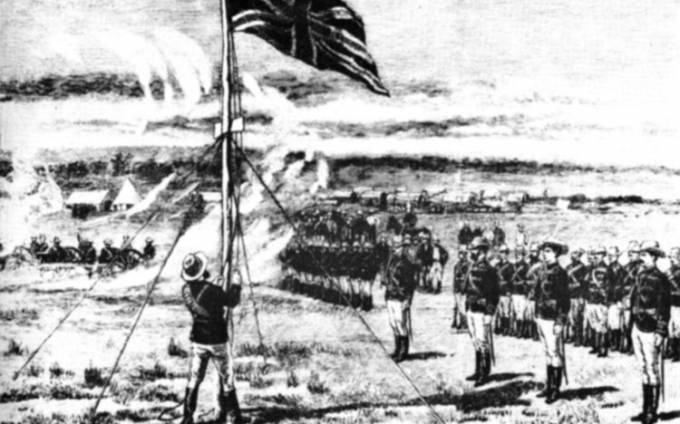

Members of the Pioneer Column hoist the Union Jack at Fort Salisbury in September 1890 to mark the beginning of nearly a century of colonial subjugation and oppression of Zimbabweans

Simon Massey Correspondent

There are many fallacies associated with the history of Zimbabwe. Let’s start with one of the oldest.

Rhodesia was not built on an empty veld. The fallacy that the land was empty is just that: a fallacy. Probably a quarter of a million Ndebele populated the south-western and arid part of the country alone, though figures for the Shona population are harder to assess. It seems certain that such an incredibly beautiful and agriculturally bountiful land was very well populated indeed at the time of the invasion of the so-called “Pioneers”.

When the “Pioneer” Column rolled into Zimbabwe in 1890, stuck the Union Jack up and claimed “Rhodesia” for the Queen of England, it did so with the full armed support and backing of the British South Africa Police. Without this support the invaders would have been pushed south and back out of the country by those resisting them. The “Pioneers” themselves were also armed to the teeth and comprised mostly of paid mercenaries in search of new gold fields with only a few genuinely adventurous settler families thrown in for good measure.

The inhabitants of Mashonaland resisted the invasion. They rose up and were often cut down in unknown numbers using state-of-the-art Maxim machine guns. Nobody bothered to keep a record of the numbers of “savages” killed. Sometimes public beheadings offered those who had not yet taken up resistance a good reason to remain uninvolved.

Rumours that some of those who were beheaded had their remains removed to the United Kingdom have become less like rumours in recent years. Remains have been returned from Germany to Namibia and from the United Kingdom to New Zealand. Negotiations to have Zimbabwean remains in London’s Natural History Museum repatriated to Zimbabwe have been underway for some time. They are predictably slow. The British are hoping President Mugabe will die before this story breaks into the mainstream.

In the book “Mugabe: The Great Betrayal”, Andrew Norman describes: “The Lippert Concession, 1899, which allowed would-be settlers to acquire land rights from the indigenous people. In practice however, the BSAC (British South Africa Company) bought land rights from the British Crown and then sold them to the settlers, the revenue accruing to the Crown and the owners of the land receiving nothing.”

To anyone with any sense of justice this is basically just legitimised land theft, and it should be born in mind when considering the land invasions and fast-track land reform that drove thousands of white farmers from the country and brought crippling, punitive sanctions, boycott and divestment from the west. Because while these white farmers were being evicted without compensation, defending land that had been stolen and then sold to them by the Crown, the Crown was sitting in Buckingham Palace counting its profits, calculating its interest, and keeping very quiet about it all. Charming.

Succinctly put: the Crown used the BSAC and the BSAP to steal Zimbabwe from its African population by force of arms, which it then sold to the white settlers. When negotiations between the UK and Zimbabwe for the UK to fund land reform collapsed in the mid-1990s, the descendants of those settlers began losing their land without compensation to the Zimbabwean fast-track land reform process: the Crown kept schtum and sat on the money.

Doug Schorr’s book “The Myth of Smith” seeks to expose much more recent secrets. But in setting the scene for the Bush War of the 70s Schorr describes some very disturbing folklore. Schorr claims he was told by an ageing settler of a time in the early 1900s when a common after-church activity on a Sunday was to hunt Africans from horse-back.

Because of the sort of people likely to buy this book, there’s going to be a good percentage of readers who do not like the conclusions it draws and will resist them wherever they can. It was a big shock to Rhodesians on the streets when the war they had thought they could not possibly lose was suddenly lost. They began to desert the country in droves even before the election that brought then Prime Minister Robert Mugabe into office, perhaps expecting that the evils of the war years might quickly catch up with them.

The Bush War was a propaganda war and as an English kid growing up in Rhodesia I was as susceptible to it as anyone else. So it was the last third of “The Myth of Smith” that interested me most because it covers the period of the 1970s when I was there. Through this portion Schorr speculates with sound reasoning that many of the atrocities associated with and blamed on the Black Nationalist movement during the war may actually have been deliberate “false flag” operations by Rhodesia’s own security forces.

Schorr sets the scene perfectly through the first two thirds of the book. He illustrates the degree of self-delusion and privilege in Rhodesia, the white public’s general sense of moral and racial superiority, and the ultimate loss of that morality. He further describes the failure of the rule of law in the country as it became more and more desperate in its war against the Black Nationalists.

Ultimately, the whites of Rhodesia fought to maintain privilege and segregation, while the Nationalists were driven by a sense of injustice. They felt disenfranchised, subjugated and even dehumanised by Rhodesian culture and racist Rhodesian government policy.

Another fallacy that circulates is that black Rhodesians lived well in Rhodesia. Of course, some did live well, but not many. If the majority of Rhodesia’s Africans lived so well how does this explain their 100- year long efforts to regain control of their country? If Rhodesia was a paradise for all in the 1970s, as ageing Rhodesians would have you believe, why were tens of thousands of Africans leaving the country to be trained to fight?

The fact is, African suffering and starvation, like the Bush War itself, was hidden away in the vast wilderness of the country, and in areas of low sustainability called Tribal Trust Lands or TTLs, where Africans were corralled and forced to live. In these barren areas the desperate struggle to survive by Rhodesia’s Africans was not often visible to the whites in the cities, cocooned in opulent luxury and protected from it all by their own sense of superiority.

A spirit medium performs a ritual among the remains of freedom fighters killed by Rhodesian security forces during the liberation struggle before the bodies were dumped in disused mineshafts at Chibondo, Mount Darwin, to conceal the atrocities

In a typical and classic insurgent technique, during the war the Black Nationalists moved amongst the population. They also relied upon sympathetic Catholic Missions for support. Schorr postulates quite reasonably that the Black Nationalists would not have committed the spate of missionary killings in Rhodesia for which they were and are still credited, because missionaries were those most likely to aid and abet them in their battle against Rhodesian forces. Many missionaries were prosecuted, imprisoned and even deported for giving medical aid, food and shelter to the Nationalists.

Schorr also throws doubt on the common assumption that the Nationalists perpetrated the most awful atrocities against the black peasants of Rhodesia.

Although it is likely that some rogue members of the Nationalist movement might have taken vengeance upon those amongst the local population who gave information to the Rhodesians, the nature of many of the atrocities suggest a more visceral hatred, and this is something that seems more likely to have been committed by those who saw or considered black people subhuman.

By turn, the Nationalists relied heavily upon the local population for support, sanctuary and succour, and were unlikely to attack their own people so viciously.

In his book “Dirty War”, Glenn Cross describes how, after becoming ill, insurgents who had been poisoned through illegal chemical weapons use would return to the last village at which they had eaten and take revenge on the villagers they assumed had poisoned them with their last meal. The Rhodesians were clever enough to use poisons that took as long as a week to produce a fatality, and it’s unlikely that any of those affected had the slightest idea that they had been made ill by a pair of jeans or a packet of aspirin used a week previously.

But that the Rhodesians were contaminating clothing, food and medicine with poisons is undeniable, and Cross provides plenty of evidence that their use was indiscriminate and often detrimental to the local civilian population.

Although it is evident that a chemical warfare programme in Rhodesia existed, the speculation regarding the pseudo terrorist units of the Selous Scouts being engaged in false flag operations is so far just that: speculation.

But this speculation is not going to be popular amongst the sort of person – ex-Rhodesians and present day white Zimbabweans – who might read this book. They might be resistant to the notion that Rhodesia was morally bankrupt from the moment Smith declared UDI and that racism and protection of white privilege brought a decade-long war of attrition to resist black governance and self-determination.

Comments