Settlements policy, tonic for housing headaches

Elliot Ziwira

Senior Writer

Having been on the city’s housing waiting list for close to two decades, Musumane Mutasa was getting impatient as signs of fatigue began to show, although he continued to soldier on for his family’s sake.

With the clock ticking the years away ever relentlessly, Mutasa’s patience continued to wane.

Would he ever hold title to a house? He always wondered!

Aware that success to his people meant owning a house in an urban area, and that there were limits to what one could endure on a monthly basis pertaining to landlord-tenant interactions, Mutasa decided to take the leap of faith that scores of people in his locality were taking.

He got entangled in a housing cooperative.

He had invested wisely in livestock and farming in his rural Murehwa, ready for the long haul, but the land barons’ call came at the opportune moment, or so he thought as he eagerly answered it.

So enthused was he that he contributed his share to catch up with those that were already part of the said cooperative, which significantly ate into his savings.

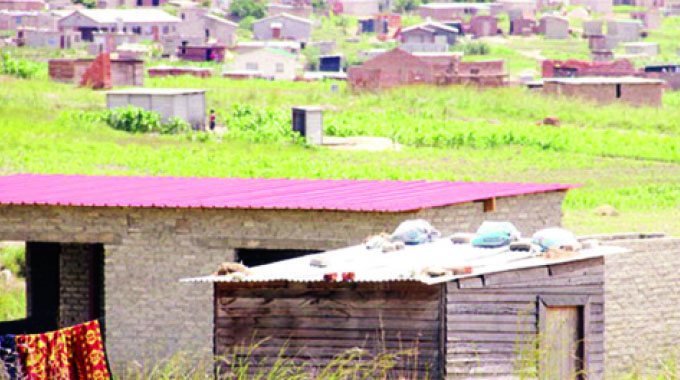

With the gods of fortune presumably smiling at him, Mutasa was allocated, among scores of others, a 1 000sqm stand in an expanse of undeveloped jungle.

Like the responsible father that he was, in no time he had put a roof over his beloved family, courtesy of his lifetime savings, a bank loan and disposal of part of his cherished herd of cattle.

An imposing five-bedroomed house, the envy of the sprawling neighbourhood, stood majestically on his allocated piece of land.

And then one wintry morning, bulldozers descended on their neighbourhood with such menacing tenacity that shamed the devil.

Along the dozers’ trail of agony, devastation and hurt, a long voyage, where many rivers and mountain ranges had to be crossed, ensued.

So deep was the wound in his heart that Mutasa, the effervescent planner, who could not envisage a time he would leave his family to the vagaries of both nature and Man, could not hold the haemorrhage inside, which clogged his vital organs.

He lost the battle ensuing from both Man and nature, thus his dream died with him, and with him it was interred, leaving behind a young widow and four minor children to battle it out with the dozers another day.

Such is the predicament of scores of home-seekers who have fallen prey to unscrupulous land barons and bogus housing cooperatives.

Millions of dollars have been lost; lives have been lost; families have been devastated, and others broken up; and dreams have been shattered through this land scam or the other.

Media space has been devoted to such sad stories, but to what end?

Although the Government has always been calling on the police to bring all land barons and leaders of housing cooperatives to book for duping desperate home-seekers, and wantonly settling people on undesignated land, mostly State land, the absence of a human settlements policy impeded justice.

Hence, Cabinet’s approval of the Zimbabwe National Human Settlements Policy last week, presented by Vice President Kembo Mohadi, as the chairman of the Cabinet Committee on Social Services and Poverty Eradication, could be the Holy Grail required in bringing sanity to settlements in line with global disaster risk reduction frameworks.

That way, home-seekers, like Mutasa will be protected at law, and those taking advantage of their plight will be punished.

Affordable housing can go a long way in eradicating poverty and creating equal opportunities for citizens, and for that to happen regulations should be put in place.

The human settlements policy is aimed at informing the implementation of relevant facets of Agenda 2030’s Sustainable Development Goals, Vision 2030 and national and international pliability frameworks.

It is anticipated, as Information, Publicity and Broadcasting Services Minister Senator Monica Mutsvangwa said at a post-Cabinet briefing then, the settlements policy will introduce a raft of measures that will ascertain the planning, development and management of settlements in line with global trends.

Disaster risk reduction frameworks, environmental and climate change policies, laws and standards followed internationally will be adhered to through the policy.

The policy will assist in mitigating inequalities between rural and urban areas, as well as addressing housing and social amenities backlogs burdening local authorities.

It is envisaged that the implementation of the policy will significantly lead to a reduction in the cost of building materials and housing finance.

The policy will, among other issues provide for disaster risk assessments, environmental impact mitigation, climate change implications integration into rural and urban settlement planning, development and management.

To curb settlement stretch, 40 percent of land earmarked for human settlement will be set aside for the construction of high-rise flats and buildings.

State land reserved for human settlements will be managed through the Ministry of National Housing and Social Amenities in collaboration with respective local authorities to ensure accountability and ease of coordination.

Under the policy, local authorities are expected to have spatial planning units, which will be manned by registered planners.

Development planning, control and facilitation in each local planning area will be done through set committees and sub-council structures.

Among its key highlights, the policy will incorporate the provision of housing for the destitute, social institutions for orphans and the aged in human settlement planning.

Victims of natural disasters, like Cyclone Idai are set to benefit from the policy, which will be implemented through a financing model that incorporates partnerships.

It has to be recalled that since Independence in 1980 the Government of Zimbabwe has been forthcoming in the provision of housing facilities, especially for low-income earners.

Between 1984 and 1993, the World Bank provided a $43 million Urban Development Loan to Zimbabwe, which was aimed at easing pressures that come with urbanisation as the country transitioned to self-rule.

The project proved that Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), which the policy seeks to foster, work as the building societies involved, chief among them the Central Africa Building Society (CABS), delivered through coming up with favourable conditions for low-income earners with the support of the central bank.

Because provision of housing cannot be the burden of the Government alone, PPPs can be sought. Private players, with Government support can get opportunities in the construction sector, a case of profitable social responsibility.

What should be guarded against is profiteering at the expense of the same people they purport to be helping.

There are houses and flats in Highfield, Mufakose, Mbare, Belvedere, Mabvuku, Mabelreign and other areas across the country that were built through Government support for civil servants.

It is not possible that all of them can get houses at the same time, but what is required is continuity.

Across the country, there are Government owned houses that civil servants occupy during their tenure free of charge.

The flipside, though, has always been that upon retirement, death or otherwise loss of employment one’s family soon finds itself on the road to nowhere again.

Since land is finite and a bone of contention globally, it has to be utilised effectively, for the benefit of future generations.

High rise flats, as envisaged in the policy, are the way to go, although in some cases they may be costly as compared to building low-cost 50 square metre houses on 200 or 250 square metre lots, considered socially acceptable.

However, when the cost of land is factored in, then high rise flats suffice.

Growth points can also be revisited, since they provide serene environments for retirement and reduce pressure on urban areas, which is causing headaches for town planners.

Furthermore, comparatively, land in rural areas is cheaper, which will go a long way in the Government’s quest to provide shelter for its employees; and other partners can also take a cue from this.

Granted, monetary benefits may be attractive for the here and now, but “we can start with housing, the sturdiest of footholds for economic mobility”, because “it is hard to argue that housing is not a fundamental human need,” as the sociologist Matthew Desmond affirms.

Therefore, companies, banks and local authorities should complement Government efforts in the provision of affordable housing units, as a progressive way of eradicating poverty and protecting citizens against scammers-induced heartaches, as enshrined in national Vision 2030, and envisioned in the recently approved Zimbabwe National Human Settlements Policy.

Comments