‘Organising resistance to colonial rule was not easy’

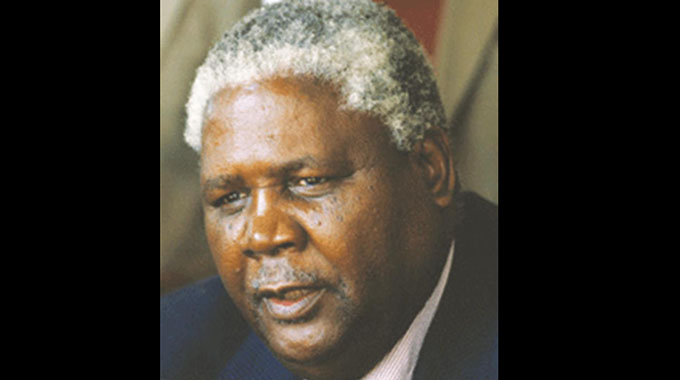

Today Zimbabwe marks the 21st anniversary of the passing away of Father Zimbabwe, Dr Joshua Nkomo (pictured), who died on July 1, 1999.

Below are excerpts from his book “The Story of My Life”, where he touches on challenges he faced in his own country under white minority rule, and what inspired him and his illustrious generation to confront the racist Rhodesian Government leading eventually to Independence in 1980.

“The management people were not surprised that I chose to live with the workers. They had come to believe that living in the compound, eating coarse food and not enjoying luxuries were part of the African way of life. It did not occur to them that we would prefer to live better if we got the chance. It was convenient to them to take that view of us.

“It became part of their way of life. I understood that, and it did not make me angry. But I resolved to confront them. It was impossible to persuade them to change. They had to be made to change. That was why I took on a third responsibility, on top of my job as welfare officer and my position as president of the railway union. In South Africa I had become very interested in the African National Congress, which was just starting to move on from being a body which merely complained about the way things were to one which developed a concrete programme for change in society. The Southern Rhodesian ANC was at this time, in 1948, a weak organisation.

“It had perhaps 5 000 or 7 000 members, and there had recently been a row in the committee. But there were some excellent people who were trying to make it more active — Clement Muchachi, Jerry Vera, Aaron Mabeza, ‘Old Man’ Dhliwayo and Edward Ndlovu. It was pretty much like it had been with the railway union: they just came to me and asked for help in getting things organised. I was promptly elected president of the ANC as well my predecessors having been Enoch Dumbutshena and Stanlake Samkange.

“It was our mission to make people believe that things could be changed. That was not easy: there was a tremendous amount of apathy. We held our general meetings in the Stanley Hall, the only public hall in Makokoba Township. If we did well, 100 people would turn up. On a bad day there were so few people that we used to meet in the little library — it was as bad as that.

“Even the committee, whose members were ordinary working people and a few farmers, did not really believe that anything could be changed; the white people were so strong and well organised, we were so weak. I travelled round the country meeting as many people as I could — I had the advantage of a railway pass, but often I had to go by bus to remote places. Muchachi used to walk miles through the bush to get to tiny places and spread the word that there was, after all, an alternative to just accepting the condition of life that the white government imposed upon us.

“All we could do about people’s grievances at that time was to find out what they were and formulate them, writing things down for the first time, organising petitions and complaining about what was wrong. I typed out resolutions and memoranda on my railway typewriter, on every imaginable subject. But whether it was labour relations or voting rights or land questions, or simply personal grievances, all communications to the authorities had to be addressed to the secretary for native affairs in the government. He very rarely bothered to reply! Half the time we did not even get an acknowledgment.

“African protests did not matter. It was discouraging. But we continued.

“It was that experience of ordinary people’s difficulties, in all walks of life and in every corner of the colony, that convinced me that no partial political reform could set matters right.

“Through my railway work I came to know not only Southern Rhodesia but Northern Rhodesia with its different form of colonial government, and Nyasaland with its apparently more well-intentioned protectorate system. I saw that the people were denied not only their rights but also their responsibilities: they were treated as children and expected to behave like children. It was an attitude of mind as demeaning to the rulers as to those who were ruled. It had to be changed, and nobody was going to change it except ourselves.

“In 1952 I unexpectedly discovered that the government of Southern Rhodesia needed me after all, even if they did not want me. The British government was trying to organise a new federation of the three separate territories in what it called Central Africa — the two protectorates of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and the ‘self-governing colony’ (whatever that might mean) of Southern Rhodesia, my homeland. They organised a conference in London to prepare for this new arrangement, and somebody in the British government — I have been told that it was the prime minister himself, Winston Churchill, but I do not know if that is true — insisted that the Southern Rhodesian delegation should include at least a token black representation. So suddenly I found myself the possessor of a brand-new passport, on an air-craft heading for Europe. This is a story that needs explaining.

“After the Second World War and the independence of India that immediately followed it, the British saw that they could not go on running their colonial empire in the same old way. Independence for the colonial peoples would have to come one day. Meanwhile they wanted to reorganise the colonies so that they would be easier to run and presumably more profitable. One way to do that, they thought, was to amalgamate several colonies into one federation. In our part of the world the British Labour government, which was voted out of office in 1951, had studied the plan for a Central African Federation of the three territories, but had not decided to go ahead with it.

“Mr Churchill’s new Conservative government were sure they wanted federation. For the white minorities in each of the territories it was a logical move. Northern Rhodesia had its rich copper mines, and needed cheap migrant labour to work them. Nyasaland had a surplus population and a long tradition of sending migrant workers abroad.

“Southern Rhodesia had a big food surplus and a much bigger white population than the other two territories — and the whites controlled their own internal affairs. By putting the three together, the British hoped to get rid of a load of responsibility, and the local whites hoped to be able to hold onto control of the whole area.

“The big companies, based in London and Johannesburg, that controlled the Northern Rhodesian mines and the Southern Rhodesian farms, thought such an arrangement would guarantee their profits for a long time ahead.

“We in the ANC suspected the idea was a bad one, but we were desperately short of reliable information on what federation really meant. The only news we got was in papers owned by companies committed to the preservation of white interests. (There was at the time no radio service for Africans in Southern Rhodesia, although we could listen to the service from Lusaka in Northern Rhodesia; but that too was really just European news edited for African consumption.)

“The one contact we had with other affected people was at the house of the Indian representative in Salisbury, a Mr Singh — he was not called High Commissioner, since the colony was theoretically not independent, but he had diplomatic status. He invited the leaders of the African National Congress in Northern Rhodesia down to Salisbury for a reception. Their leader was Harry Nkumbula; also present was a quiet, serious young man who impressed me very much. His name was Kenneth David Kaunda, and he struck me as a deep thinker and kindly man.

“The British government, before imposing federation on the three territories, had to go through the motions of discussing with the people who lived there.”

Comments