New stimulus for Marechera scholarship

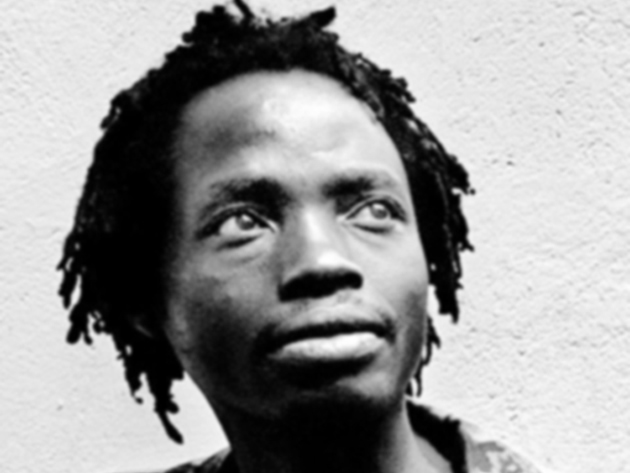

Dambudzo Marechera

Stanely Mushava Literature Today

Dambudzo Marechera’s startled impression of the world is the subject of enduring interest almost three decades after his death.

Last week, Flora Veit-Wild, his liaison, biographer and perhaps the principal custodian of his estate, handed over all the Marechera material she had kept since the time of his death – documents, photos, video and audio files to Humboldt University in Germany.

“There exists thus a comprehensive Berlin Dambudzo Marechera Archive. It is accessible for researchers both, in physical form at the University Library, and, digitalised, in a media repository on the university website,” Veit-Wild said in a statement.

The multimedia trove is likely to ignite fresh interest among the legion of Marechera scholars and fanatics ever ready to fasten on to his words and make something new of his estate.

There has been a sustained current of Marechera journals and books in recent years, including “Moving Spirit: The Legacy of Dambudzo Marechera in the 21st Century” (2012) edited by Julie Cairnie and Dobrota Pucherova and “Reading Marechera” (2013) edited by Grant Hamilton.

Earlier this year, The Scofield, a US-based online magazine, published a commemorative issue on Marechera.

The issue, “Dambudzo Marechera and the Doppelganger”, examines various aspects of the author’s work and the idea of a “double” which recurs in his work.

In this edition of Literature Today, we reprint from the issue different authors and scholars’ impressions of Marechera’s books.

China Mieville on “Mindblast”

It may seem perverse to recommend starting a writer’s oeuvre with a book that’s nearly impossible to get hold of, never published outside of Zimbabwe, but the qualities of Mindblast are utterly real and powerful. It is a perfect portal to this gutter Modernism, eliciting something much deeper than merely a rarity-hunter’s swagger.

Mindblast is not a patchwork but a constellation. It winds through the urgent clatter of all Marechera’s forms: plays and stories and poems, with their incomparable names. No poet before or since him has ever bestowed titles on their work with such breathtaking vatic precision, made the contents-lists of their poems such astounding metapoems themselves.

The book concludes with what is —perfectly unconvincingly — called an “appendix”: a long section from Marechera’s precious, infuriating, searing, and achingly moving diaries. Down and out, abasing, self outcast in his own mind.

Excoriating identity. A retelling of his childhood, his work of salvage. Whole post-colonial genres and movements of theory shortcut in his elegy of becoming, of his boy-self finding an offcast encyclopedia the tip “where the garbage from the white side of town was dumped”.

Marechera self-constitutes out of the poisonous surrealism of white supremacism and empire, “a chance encounter with a Victorian imperialist on a rubbish dump in a small town in Zimbabwe”.

Tendai Huchu on “The House of Hunger”

“I got my things and left,” is one of the most iconic opening lines in world literature. And from there, it’s a rollercoaster though the intriguing stream-of consciousness style by which Marechera presents his novella and short story collection.

The language is fractured and crackling with an intensity that sizzles right off the page. Though, of late, Marechera is more known for his whacky antics — tossing plates and insulting his hosts at a posh awards dinner, heavy drinking, womanising and general douchebaggery — it is a pity readers have not better embraced this “enfant terrible of African literature”.

They would be well rewarded reading this vibrant, thought-provoking, and unsettling masterpiece that is both brutal and moving, and provides a rollicking ride through the splintered psychology of a rare literary genius.

Tinashe Mushakavanhu on

“Black Sunlight”

I was 13 years old when I first read “Black Sunlight”, mostly for its vulgarity and honesty. I conspired with a friend to steal the only copy the school library had. We read it between ourselves until it was a dog-eared rag tag.

The whole experience was dream-like. Its nightmarish visions are haunting. What Marechera was doing in this odd and awkward book was to explore anarchism as an intellectual position. It’s curious that anarchism as a political philosophy remains maligned in Africa.

Chaotic boundaries between fantasy and reality characterise the book. It exhibits the fragmentary genius of Marechera with its astonishing fluency and rawness. Here is a writer whose words drop mental and violent on the page.

You hear the words so vividly and feel all over again, the ringing of your own madness. Marechera’s characters are complex and he plays with time in the most vivid and filmic way.

David Buuck on “The Black Insider”

“The Black Insider” is one of several works left unpublished during Marechera’s life, having been abandoned in the late seventies after being rejected by Heinemann’s Africa Writers Series.

Compiled and edited by Flora Viet-Wild, who also contributes an extensively researched and insightful introduction, the book was the first of what would become several posthumous publications of Marechera’s diverse body of work.

Along with the title novella, the book collects three devastating short stories and two explosive poems that reflect upon exilic and black British life in the late 1970s. Marechera, who lived in a London squat while writing most of the book, sets his novella inside a former Faculty of the Arts building, where a number of artists and intellectuals hole up during an encroaching war/plague/social apocalypse.

Social outcasts and outsiders, here “insiders” within the ruins of “Art”, debate aesthetics and politics in a digressive, carnivalesque style that is more experimental than even Marechera’s later Black Sunlight.

Featuring brilliant passages laced with references to avant-garde literature as well as African cultural politics, Marechera investigates the African exile’s life inside the prisms (and prisons) of his own mind as well as those of racist Britain.

Fusing form and content in a manner that produces fever-pitched writing, “The Black Insider” is a crucial addition to the Marechera corpus.

Gerald Gaylard on “Cemetery of Mind”

Flora Veit-Wild compiled and published “Cemetery of Mind”, the only extant collection of the poetry of Dambudzo Marechera, in 1992. In her “Editor’s Note”, she wrote: “Arguably, Dambudzo Marechera’s real talent lay in the art of poetry.”

For all that he has become most famous, if not infamous, for his first novel “The House of Hunger”, I would tend to agree that Marechera’s Dionysian disposition was probably best suited to the shorter form of poetry.

Able to give the black electricity of his inner nerves to the immediacy of poetry without censorship or the constraint of narrative’s long term demands, his poetry contains amongst his most intimate, emotive, visceral and free writing.

Here was the form to which he confided his most acute political cynicism, his most tender love and scathing rancour. It also contains some of his most potent formal interventions which demonstrate not only an immersion within inherited Western forms, like the sonnet, but also a refreshing iconoclastic relish for freedom and innov- ation.

If we want to understand Marechera’s contribution to literature, then we can do worse than turn to his poetry and wonder at the insecurity and insouciance we find there.

Scott Cheshire on “Scrapiron Blues”

One often comes to a great artist by way of their most famous work. Picasso’s “Guernica”. John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme”.

Less often, one finds the work of an artist by way of their lesser-known stuff, forgotten work, their B-sides. My introduction to Dambudzo Marechera was through “Scrapiron Blues”, his final posthumous collection of uncollected work and literary bric-a-brac.

It is indeed a terrifying compilation, nightmarish and otherworldly. And yet for that it is utterly human, full of sadness, and endlessly interesting. A book full of ghosts, it reminded me of my own.

Comments