Mbuya Nehanda must be turning in her grave

Ruth Butaumocho Gender Editor

ON April 27, 1898, the district surgeon of Salisbury (now Harare) wrote: “I certify that I have examined the body of Nianda (Nehanda), upon whom sentence of death has been executed, and that life is extinct.”

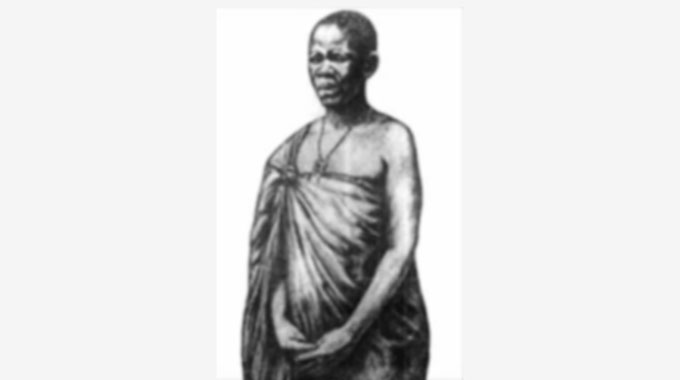

That statement signalled the end of the beginning of an era for the gallant, defiant and fierce heroine of the First Chimurenga, Mbuya Nehanda, the legendary spirit medium from Mazowe.

In his book “Inside the Third Chimurenga” (2001), former President Robert Mugabe states that Mbuya Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana was sentenced to death by hanging by British colonialists on April 27, 1898.

This is corroborated by a number of historical sources, although other sources claim that she was executed on April 28.

Although the date of hanging and the place where she was hanged continue to be points of contestation among historians and other researchers, today (April 27) marks 120 years since her death.

While the day might appear like any other, it is pregnant with historical significance, and gives an insight into the life that the majority of Zimbabweans endured under colonial rule and its consequential effects.

April 27 is a special day in the lives of millions of Zimbabweans across the political divide because it represents the crystallisation of their hopes and aspirations, the legacy of quest for self-determination and the independence that the country enjoys today.

To this day, Mbuya Nehanda remains one of the revered gallant heroines who was instrumental in the liberation struggle and her contributions cannot be quantified.

However, the commemoration of Mbuya Nehanda’s death comes at a time when thousands of women are finding it difficult to penetrate leadership spaces due to myriad factors.

The majority of women in the new Zimbabwe are bemused by the political leadership matrix where they are failing to establish a firm footing in politics, more than 120 years after Mbuya Nehanda laid the groundwork for engendered leadership through the role she played during the First Chimurenga and how revered she was during the Second Chimurenga.

With election campaigns having reached fever pitch, hundreds of women who are part of the fray are already crying foul over the playing field which they deem to be “choking and heavily polluted”.

The ruling Zanu-PF party’s National Elections Commission (NEC) is inundated with complaints from prospective female candidates alleging that they were disqualified at district level, when their CVs should have been forwarded to the NEC, as stipulated by national political commissar Lieutenant-General Engelbert Rugeje (Retired).

In fact, local political parties always promise gender parity when it comes to political representation, but usually fewer women find their way into the echelons of power.

What is needed is a deliberate move to promote women to participate in politics, starting with the grassroots.

In the last election, MDC-T promised that it would field more women, but come election day, very few participated and only a few of them found themselves in Parliament or other high positions.

This time around, the Nelson Chamisa-led MDC-T faction has promised that 50 percent of its 2018 election candidates would be women.

But analysts doubt the political will by the party leaders to achieve such a feat, considering its past disregard of female candidates.

Analysts feel the Chamisa-Thokozani Khupe debacle over the control of the opposition party, which is before the courts, could be a pointer to the gender trajectory in MDC-T factions.

Mbuya Nehanda must be turning in her grave, for the maligning of the female population, yet the late gallant fighter inspired two revolutions that were part of the political upheaval that ushered in the independence struggle.

I am sure one of the reasons she fiercely fought was to ensure that leadership would be assumed by capable individuals and not be based on gender, race or creed.

The fact that she took her fight across the country shows that she was never concerned about regionalism, neither was she so petty to let gender cloud her judgment on matters of national importance.

Deemed to hail from the “fragile other”, Mbuya Nehanda commanded so much respect from the gallant fighters who did not deride her gender, but respected her spiritual guiding role in the struggle for decolonisation.

Despite limited resources, she led the black resistance and fought the whites with spears, bows and arrows, while the enemy used Maxim guns.

Even when the rebellion failed, she was among the last of the leaders to be captured because of her resourcefulness, not her femininity.

Together with another leader of the rebellion, the spirit medium Sekuru Kaguvi, Mbuya Nehanda was sentenced to death and hanged by the British on April 27, 1898, but her heroic role has made her the idol of modern day Zimbabwean revolutionaries.

By certifying “Nianda” dead despite having hanged her in public for everyone to see, the Salisbury district surgeon did not want to take any risk, and have Mbuya Nehanda “terrorise” the British colonial system again.

Even the British did not regard Mbuya Nehanda as a “fragile other”, which has become known by the majority of the male population, but found her to be an unrelenting revolutionary who could only be silenced by the noose.

Sadly, she must be turning in her grave, looking at how the female populace has been relegated to the periphery of the struggle, which she fought so hard to win.

Her spirit is probably trying to understand why the nation she fought so hard to liberate is negating the female leadership, in which she should be taking part.

Comments