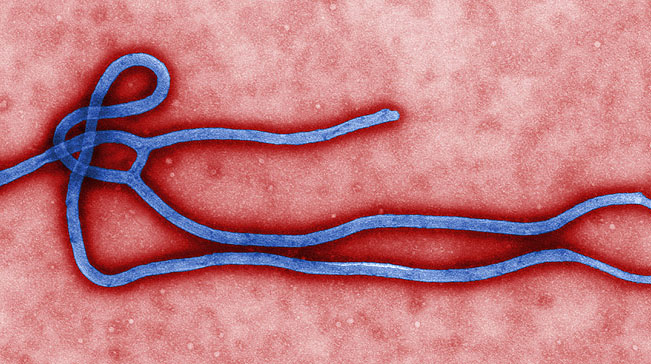

How DRC’s Ebola Outbreak has been contained

KINSHASA/NEW YORK. – The Ebola outbreak in Congo has been closely tracked and, so far, well-contained, in stark contrast to the 2014 West Africa outbreak that killed thousands of people.

Despite 28 deaths as of early June, health officials are cautiously optimistic that they are bringing the outbreak under control. So far, it’s a striking turnaround from the 2014 West Africa outbreak, which killed more than 11,000 people in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, and travelled as far as Glasgow, Scotland, and Dallas, Texas in the United States.

Despite difficult-to-traverse terrain and local communities’ skepticism of health care workers, from the start of the outbreak, officials got in front of the disease and kept it in check. Several factors made the DRC response markedly different than previous outbreaks, saving countless lives.

- Long distances between villages and an underdeveloped infrastructure slowed the spread of the disease.

The DRC’s remoteness made it difficult for health care workers to access affected communities, but it also impeded the spread of the disease. For the most part, infected individuals did not leave their communities, and outsiders didn’t come in, greatly limiting the number of infections. In contrast, in 2014, at the height of the West Africa epidemic, Ebola spread quickly through densely populated cities.

“The risk zero doesn’t exist. That is what we need to have all in mind. The risk for the virus to escape to neighbouring countries is there. But with the actions – the strong actions that the government is taking now – it can limit the spread of this disease, first of all in the Congo itself, and in neighboring countries,” said Djoudalbaye Benjamin Head of Policy and Health Diplomacy, Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

- A highly effective vaccine, in development for more than a decade but not made available until the end of the West Africa outbreak, was deployed almost immediately in the DRC.

The vaccine, V920, though still experimental, has proved highly effective in preventing the transmission of Ebola. It’s difficult to transport and available in limited quantities. But health care officials have found workarounds.

They ship the drug in specialised containers that keep the temperature below the required -60 degree Celsius threshold. And they administer it using the “ring vaccination” approach, which involves targeting individuals most likely to come in contact with infected patients.

- Local communities have been receptive to health care interventions.

Residents have questioned health care workers’ intentions, the efficacy of the experimental vaccine and even whether Ebola is real. Despite these misgivings, affected communities have been receptive to being vaccinated.

As of June 10, 2,295 people have been vaccinated in Wangata, Iboko and Bikoro. Those vaccinated include front-line health workers, along with people exposed to individuals with confirmed cases of Ebola, and their contacts.

Officials have engaged in a multipronged awareness campaign, including mass media, training for local journalists and meetings with local leaders, the WHO said.

- An improved international infrastructure to respond to disease outbreaks proved effective.

When Ebola struck West Africa from late 2013 to early 2016, the continent had no central body to help prevent, track and manage emergency responses to infectious diseases. That changed in January 2017, with the launch of the Africa Centres for Disease Control.

As part of the African Union, the Africa CDC aims to improve the continent’s public health infrastructure. In the DRC, that has involved providing support to national efforts via an emergency operation center, deploying an epidemic response team and earmarking $250,000 to help fund the response.

- Maps, satellite imagery and other data sources armed responders with information to make timely, well-informed decisions.

Congo’s remote landscape and poor infrastructure have challenged health care workers trying to reach affected communities. Out-of-date census information and inaccurate maps have further complicated the response because officials rely on accurate data to understand the lifecycle of an outbreak.

That’s prompted experts such as Cyrus Sinai, a University of California, Los Angeles cartographer, to get involved.

Sinai worked with the Ministry of Health, The Atlantic reported, to update old, inaccurate maps and conduct a “microcensus” to estimate population sizes.

Plans are also underway to build a continent-wide database. That would help in capturing information to aid future outbreak response efforts. – VOA News

Comments