Glen Norah: Where football ruled, CAPS Utd were kings

Elliot Ziwira Senior Writer

In 1972, the Australian trio, New World, released a song, which was later popularised by the British band, Smokie, following the release of their version in 1976.

The timeless oldie is “Living Next Door to Alice”.

There are so many versions of it now, under different titles, but maintaining the same lyrics.

The song’s lyrics are telling, as they explore the way it feels to live next-door to someone whom one is smitten with, yet lacking the guts to utter the magic words, until it is too late to do so.

The protagonist in the song has lived next-door to the beautiful Alice for 24 years.

In fact, they had grown up together as friends and neighbours.

For 24 years, he waited for a chance to express his feelings for her; until the beauty leaves without any explanation, leaving the lovestruck hero heartbroken.

As Alice gracefully gets into the “big limousine”, before it “pulled slowly out of (her) drive”, sadness and regret play havoc inside him.

His childhood sweetheart has grown out of his league.

She has always been a star in the making, and sadly, he didn’t realise it.

Puzzlingly, Sally, Alice’s friend, is the one who informs him of Alice’s departure, not that she is obliged to, but she has also waited 24 years for him to notice her.

Sally now has a chance to fill the void left by the enigmatic beauty, beseeching the protagonist to “get used to not living next door to Alice”.

But he is still hurt, and intimates that he “will never get used to not living next door to Alice.”

The hero’s hurt, procrastination and feelings of betrayal are not unique.

They are a culmination of how we take those close to us, or in our ’hood, for granted. It takes long for it to register in us that we are or may be living next-door to celebrities or future luminaries.

Our neighbours, no matter what the outside world says about them, remain just the fellows or gals next-door. To us in the neighbourhood, they are just part of us; fellow ghetto boys; until, of course, they decide to leave, or the heavens claim them.

As Smokie’s “Living Next Door to Alice” plays out in the mind on repeat, nostalgia draws the soul to a valley rich in talent, which lay about 15 kilometres south-west of Harare.

This glen is never short of renewal batteries, and always stands in the prime of time, yet the radar appears to avoid it. Colonial governments named this space Glen Norah, and Independence has long since christened it.

It is a vale of talent that has produced stars cutting across the entire spectrum of human endeavour. And, it continues to do so, yet the griot, our modern recorder of history, shies away from this area.

I grew up in Glen Norah A, kuChitubu, kumalines eMetal Box, to be precise, and I must say, I have interacted at a personal level with many celebrities cutting across various professional fields.

I know there are some that read like the beautiful Alice in Smokie’s “Living Next Door to Alice”.

I played with them, saw them rise to prominence, and feel that maybe, I should have told them how I felt about them.

Yes, Glen Norah is a home of talent. From sport, music, arts, modelling, journalism, law and business; you name it. Sons and daughters of this vale are all over now, announcing their mettle in chosen areas of the stars, putting our hood in the limelight; making us so much proud.

Glen Norah, which is bordered by Glen View, Waterfalls and Highfield, inherited the name “Norah”, from farmer Baxter’s wife.

This “Bhakasta”, as we picked it out from the ghetto lingo of our childhood, owned a farm on whose soil Glen Norah and Glen View now stand.

Since a glen is a valley, Glen Norah literally means Norah’s valley or vale, while Glen View depicts a view of the glen, because it is situated on higher ground.

Baxter’s farmhouse still exists where St Peter’s Kubatana now stands, and some of the outbuildings are used by Harare City Council as offices.

We used to go kwaBhakasta (at the Superintendent’s) to pay our rates.

In this valley, there is a dam, which is now part of the Glen Norah Park. The park has seen better days. Now, it lies forlorn, and appeals to the heavens for a return to the greenly days.

In the 1960s, before the birth of the residential area, the dam used to be bigger than it is now. Baxter used it for his farming activities.

What has prompted this piece is not nostalgia per se, which of course may be partly true, nor is it a case of blowing one’s own trumpet, though trumpeting is not a bad idea after all; but the desire to recognise the heroes in our neighbourhoods before “outsiders” claim them.

Some were thrust into this space through occupations, courtesy of their employers, some were born and bred there, and others became part of the ’hood through acquisition of properties.

The high-density suburb that nurtured us, is divided into three sections; A, B and C.

The first two sections were birthed in the early 1970s, and the last section came into being after Independence. The 6 400 houses making up Glen Norah A and B were constructed by John Sisk & Son (Rhodesia) between 1971 and 1973.

In Glen Norah A, for example, where I grew up, sections are either known through beerhalls or company-allocated houses.

One talks of Chitubu, Spaceman or Zvimba, which are beerhalls, or kumalines eMetal Box (the company my father worked for), PTC (Posts and Telecommunications Corporation), Rothmans, CAPS, Sisk, and National Breweries, among others.

There were also council houses.

As a result of the many companies that built houses for their employees in the suburb, there was a sense of community, and a kind of connection, especially when it came to supporting each other in terms of talent.

We literally knew each other well.

Reading was a pastime then.

We would share stories from novels (Shona and English), and anything in print. Reading was the in-thing, and eloquently sharing such experiences as portrayed in the written word would evoke awe, for those known to have “eaten book” were gods.

We would share books, magazines and newspapers until they were reduced to dog ears or were in shreds.

We would go kufirimu at Glen Norah Hall, courtesy of Mandebvu Film Shows. We would also watch football at Glen Norah Stadium, or at the playground (pamatombo) to the south of Glen Norah Hall.

There was one team, Bvekerwa, which I still remember from those nostalgic days.

Six or seven days a week, we would set our goalposts in the streets, and chase after chikweshe.

Eight times out of 10, we knew the drivers, and occupants, of the passing jalopies (Zephyr Zodiacs, Morris Minors, Ford Cortinas, Peugeot 404s/504s, Toyota Crowns and “half-tonnes”) by name.

We would play a fast-passing game, whose rather vulgar name I cannot repeat here — the one in which a guy would be chasing the ball, and, whoever had the misfortune of losing it, became the tail chaser; you remember it?

We would draw lines to mark tennis courts on the tarred roads, yes, neatly tarred roads. There were no dusty streets in the ghetto of our childhood.

With our improvised rackets we would sweat it out on the “court” until Papa appeared, and we would know that it was time to water the garden.

And, if it so happened that one of our peers chanced on a real soccer ball, golf ball or cricket ball, gosh, it would be hallelujah.

We would immediately create pitches and improvise golf sticks and bats, to hoist ourselves into the hilarious world of the other side of the quo.

We would walk to Afgate, in the Willowvale industrial area, to fetch pieces of wire for the designing pleasure of “car manufacturers” among us.

I guess we had so much energy to spare. That way, talents were identified and nurtured, in the ghetto streets of our dreams. There was so much raw talent waiting to be discovered, or discovering itself, maybe.

Secondary school separated us a bit as some of us would go to boarding schools or the so-called former Group A schools, and others would go to supposed Group B schools.

Western forms of education would further separate us at Advanced-Level, and careers placed a wedge among us as the stars shone differently on our aspirations.

However, the ghetto remained, and still remains our link.

While others have moved to other suburbs, affluent or otherwise, cities and towns, where blending-in is becoming a challenge, as the ghetto refuses to leave our lot, some have remained. Still, some have joined the trek down south or further across the oceans and seas yonder, depending on the call of the hornbill.

Yesteryear soccer greats

Glen Norah produced quite a number of football stars, some of whom have long since hung up their boots, while some have departed to the other side of life across the bridge. And, some are still actively involved in the beautiful game in their own small ways.

These stars fall into different eons, as will be explored.

For starters, there is no way one can write about football in Zimbabwe, without mentioning George “Mastermind” Shaya.

I am not a Dynamos fan; that I must tell you unapologetically, straight away

Though we grew up as karate disciples, my elder brother, Shepherd, and I were football fanatics. We fell for CAPS United the moment we “discovered” football.

We knew most of the players, like Freddy Mkwesha, Shacky “Mr Goals” Tauro, Friday “Breakdown” Phiri, Oliver Chidemo; and later on, Edwin Farai, Basil Chisopo, Tobias “Rock Steady” Sibanda, Francis and George Nechironga, Oscar “Simbimbindo” Motsi and Kudzanayi Taruvinga.

Other soccer greats, who emerged from the glen, are David Phiri, Tidings Keta, Benjamin Mpofu, Mike Madzivanyika and Amidu Hussein.

This generation of players was followed by the likes of Vitalis Takawira, George “Gazza” Mandizvidza, Dumisani “Commando” Mpofu, Lloyd “Toga” Pfupa, Robson George, Mike Temwanjira, Justman Kopera, and others already mentioned.

However, the rich valley was not yet done. From its belly new gems continued to sprout.

Out came Tinashe “Father” Nengomasha, Dickson Choto, James Matola, Artwell Mabhiza, Washington Pakamisa, Tsungai Mudzamiri, Rodney Makawa, and later Abbas Hussein.

Nostalgic memory recalls that there were houses, and a flat, for CAPS Private Limited employees, the owners of CAPS United Football Club then, in the glen. We had friends kuZvimba, where these houses were, and whose parents worked for CAPS.

We frequented the green CAPS block of flats in Glen Norah A.

So, naturally, CAPS United was our home team—they were kings. My late father and brother, Andrew, also late, were avid Dynamos fans.

My father had a personal attachment to some players like Simon Mudzudzu, July “Jujuju” Sharara, Shadreck and Oliver Kateya, who once played for Metal Box, and later joined the Glamour Boys.

My mother supports Dynamos because of the same attachment.

To blow their bubbles, my brother Shepherd and I would always remind them of the day the Cup Kings – CAPS United – beat Dynamos for seven (7-0).

It was mainly for my father and brother Andy, as well as the Metal Box connection at the personal level, that I developed a soft spot for the Glamour Boys, although I worshipped Makepekepe, and still do.

The other reason being that the Mastermind’s story escaped from the books we read in school, to carry a personal attachment linked to his son Stan, and my friend Sylvester Kasikwale.

Sly is an uncle to the Mastermind, and I first met the legend through him. Shaya owned a house kuSpaceman.

But before then, I simply couldn’t ignore the Razorman, Moses Chunga, another great from our ’hood. I know those from other hoods may want to claim him, and I will explain why.

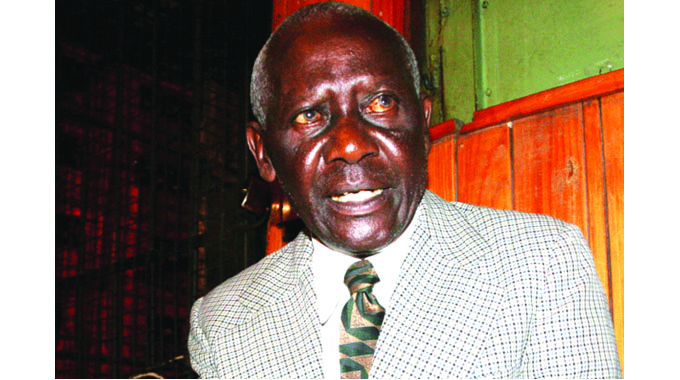

Born on October 30, 1946, George Shaya played for Dynamos and the Rhodesian national team, during the 1960s and 1970s.

The Mastermind, who died on August 24, 2021, won the Soccer Star of the Year award a record five times, including three times on the trot.

It is, therefore, not off the mark to say he has no equal in Zimbabwean football.

He also made it into the South African league, turning out for Moroka Swallows in 1975.

Sadly, by the time he died, Shaya had lost part of the apparatus with which he plotted the downfall of many rivals on the turf — his left foot—through amputation of the lower limb of his leg.

May the football gods and history’s deities remember the talismanic Mastermind as he takes the inevitable final rest. He remains a hero, not only to the Glen Norah community, but to the nation of Zimbabwe.

Oliver Kateya, Shadreck Kateya, Simon Mudzudzu, July “Jujuju” Sharara, Oliver Chidemo, Freddy Mkwesha, Jawet Nechironga, David Mandigora, and David George fall into the generation of yesteryear greats whom we had no chance to witness play, but have known since childhood.

They were from our ’hood, and we interacted with them as our parents. The Metal Box link is simply difficult to overlook here.

For those not in the know, Metal Box featured in the Rhodesia National Football League (1962-1979), the precursor to the Zimbabwe Premier Soccer League, known as the Super League then.

The team won the championship in 1973; the year in which it was promoted into the First Division; with Highlanders as runners-up.

Mudzudzu, Sharara and Kateya cut their teeth at Metal Box.

Sharara, named after the month in which he was born, July, discovered his dribbling wizardry at Feoch Mine in Mutorashanga in 1969.

Lured by Harare, then Salisbury’s neon lights, Sharara found himself in the capital, where a friend, Mudzudzu encouraged him to tempt the football deities at Metal Box in 1970, under coach Davey. Thus, an epic dribbling story, which eventually saw him replacing Shaya at Dynamos, began.

Sharara, Mudzudzu and Kateya featured in the title-grabbing Metal Box team of 1973. Other members of the team were Sunday Marimo (Chidzambwa), John Humba, Shadreck Kateya, Mike Chidzero, and Chita Antonio.

Chibuku Shumba, later known as Black Aces, won the league title in 1975.

Sharara won four consecutive league titles with Dynamos between 1980 and 1983.

He then left to join Black Mambas in 1984.

After hanging his boots, Sharara had coaching stints with Support Unit, Sporting Lions, Orapa Wanderers, Black Mambas, Mazowe Mine, Manzini Wanderers of Eswatini (Swaziland) and Mutare United. He also assisted at Dynamos.

Mudzudzu would later leave the ghetto for the affluent valley of Glen Lorne, Alice style, although he continued working for Metal Box until 2014.

Comments