First steps that smashed racial walls

Lovemore Chikova-Development Dialogue

As Zimbabwe approaches its 41st Independence Day on April 18 this Sunday, it is important to have a reflection on the daunting task that faced the new Government in 1980.

The biggest task, apart from national reconciliation, was to kick-start an economic developmental trajectory that could break racial walls built over 90 years by the white minority regime.

After the first five years of independence, the Zanu PF Department of the Commissariat and Culture wrote a book titled: “Re-building Zimbabwe: Achievements, Problems and Prospects”, which captured the journey travelled so far in trying to bring economic development and social justice.

The department recorded that more than 1,4 million people had been reduced to beggars and squatters in their own country and in neighbouring countries due to the war and racial policies of the settler regime.

More than 1 830 boreholes and 425 dams and weirs had been severely damaged, with 1 600 dip tanks out of a total of 1 800 also having been destroyed or damaged.

At least 2 000 out of a total of 2 500 primary schools and 180 out of 240 clinics in the rural areas were also severely damaged, with others completely destroyed.

In agriculture, 56 out of 74 small-scale irrigation schemes in the communal areas had been destroyed or damaged because of the war.

Many rural businesspeople who were being accused of using their businesses to support the liberation war fighters had their business infrastructure destroyed or damaged.

This uncalled for approach by the white settlers led to 4 000 such small businesses in the rural areas out of 13 000 being completely destroyed to severely damaged.

The discrimination by the white minority regime had resulted in locals being denied access to education and health facilities, a situation worsened by the destruction of schools and clinics caused by the war.

Apart from the destruction of the infrastructure, a number of able-bodied men and women had been killed during the war, leaving many families without potential bread winners.

Growth with Equity

The developmental trajectory in Zimbabwe before independence was biased towards urban areas and farms where the white minority lived.

The new government’s first economic developmental programme instituted in 1981 was called “Growth with Equity”.

The major thrust was to bring social infrastructure to rural areas where the majority lived, with the purpose of bringing the once marginalised areas in line with the new developmental trajectory.

Growth with equity was necessary as it touched on areas like education, health, agriculture, employment and several developmental projects.

Resources had to be distributed equally so that all people could have access to education, health facilities, employment and land.

According to the Growth with Equity document, the policy was meant to “achieve a sustained high rate of economic growth and speedy development in order to raise incomes and standards of living of all our people and expand productive employment of rural peasants and urban workers, especially the former.”

The policy formed the basis of other empowerment programmes like land reform, education-for-all and health-for-all.

Land Reform

Access to land was one of the major reasons why Zimbabweans took up arms against the Ian Smith regime, and correction of the imbalance in ownership was widely viewed as social justice. At independence, the newly-elected Government concentrated on resettlement, increased agricultural productivity through infrastructural development and increased agricultural loans.

According to the then Zanu PF Department of the Commissariat and Culture, these moves resulted in an “unprecedented surge in agricultural productivity with marketed surplus in maize increasing from a mere 80 000 tonnes before 1980 to 400 000 tonnes in 1982. Before Independence, land was divided between blacks and whites, with communal lands comprising 41 percent of the total land, yet supporting more than 80 percent of the population.

Commercial farming areas took over 40 percent of the total land, but owned by a mere 6 000 white farmers.

This state of affairs was obviously untenable in the newly-independent Zimbabwe and the Government set about to redress the imbalances by acquiring land from the exclusively white farming areas.

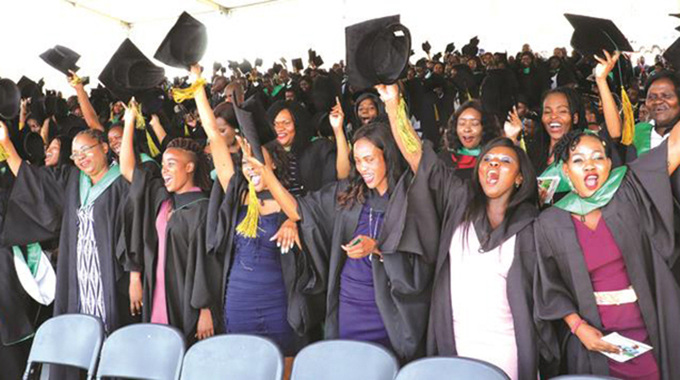

Education-For-All

To develop the new country, there was need to have an educated majority who would play a major role in moving the economy forward.

The new government was quite aware that the skilled manpower that was concentrated in the white minority would soon become scarce as they migrate back to their ancestral lands.

And indeed, it happened that a number of whites were not impressed by losing their dominance, and could not take the coming of independence lightly, thus deciding to leave the country.

Apart from the need for an educated labour force to replace whites who were leaving, there was a pressing need to ensure that locals accessed education as a human right.

Education-for-all was meant to correct the crooked system which was being driven by racist policies which ensured very few blacks went beyond certain levels of education.

The free education policy adopted by the new government became one of the pillars forming the basis of development in Zimbabwe.

The Zanu PF election manifesto of 1980 was very clear on what the new education system meant to achieve:

“(a) abolish racial education and utilise the education system to develop in the younger generation a non-racial attitude and a common loyalty to the State;

(b) establish a system of free and compulsory primary and secondary education;

(c) abolish sex discrimination in the education system;

(d) orient the education system to national goals;

(e) give every adult who had no or little educational opportunity the right to literacy and adult education;

(f) make education play an important role in transforming society; and

(g) place education in the category of basic human rights and strive to ensure that every child had an educational opportunity to develop his mental, physical and emotional faculties.

Health-for-All

Access to health had been problematic for the locals before independence, and it was incumbent upon the new administration to ensure that there was equity in access to health.

A lot of rebuilding needed to be done in rural areas to restore health facilities that had been destroyed by the war. This means heath-for-all was mainly about providing health facilities and ensuring that people access them for free.

The advantage of a health population cannot be overemphasised when it comes to pushing a developmental agenda.

Health service centres were concentrated in urban areas, despite the fact that nearly 80 percent of the population at that time lived in the rural areas.

This meant that most resources for health during the colonial era were being directed towards urban areas to service just a smaller section of the population, which ensured that only whites benefited.

The remedy initiated by the new government at independence was to increase the number of health service centres in rural areas, a move that drastically improved access to health by the rural folk.

Positives

It was clear that the government at independence faced a number of priority areas, including creation of conditions necessary for peace and national unity. Government was also concerned with laying down the backbone for political, economic and social development that would transform the country.

The reconstruction programme, which cost millions, and the rehabilitation of infrastructure were important in determining the new direction the newly independent Zimbabwe was to follow.

Comments