Feeling good for nothing

where you were across Africa.

Political power that does not transform into military and economic power is good for nothing, and after more than 50 years of independence Africa has learnt the painful lesson the euphoric feel good factor that came with the victories of our liberation struggles across the continent was, in fact, a good for nothing feeling.

We must always examine ourselves honestly in our exaltations for the virtues of democracy, and even in our respect for the nobilities of the human rights doctrine, universal and all appealing as it may all appear.

Democratic values are not as tenacious as the charlatans in the democratisation crusade often make them appear and the illusion that we simply need a viciously strong relationship with democracy preachers from the West for us to be democratic is dangerously misleading, if not politically fatalistic.

We today have ambition-obsessed politicians whose political preoccupation is nothing but an inspiration to climb the echelons of power, and often they rely on the energies of feel good youthful activists crazed to no limits by a hysterical obsession for undefined change, sometimes even indefinable.

An average youth activist in Zimbabwe’s MDC-T chants endlessly about change, but they have no idea what exactly it is they refer to as change — often limiting it all to the changing of holders of political offices.

For as long as our politics are defined by power mongers masquerading as political leaders, and for as long as emotion-charged youthful activists continue to chant the majority into prescribed voting patterns, we Africans risk to die feeling good for nothing — falsely believing in democracy that never was.

Celebrating empty promises as happens with audiences of preachers of the contagiously impressive prosperity gospel is sometimes compulsive, but the empty feel good factor does not and cannot in itself bring any wealth to the impressed. No preacher can preach away poverty, regardless of his charisma or eloquence. Similarly political power that is not transformed into economic power is like the sweet sermon of prosperity gospel that is not followed by the principles of hard work, or by the diligence prescribed in the scriptures.

It is about time we Africans began to take governance issues seriously by focusing on core issues at the heart of the continent’s needs.

History has taught us dependency and how best to articulate our dire needs for the sympathy of foreign donors, especially for the sympathy of the Western donor. We must of necessity disengage our people from this lethal and fatalistic history that has taught us to look up to Europe as the mountain from which salvation is destined to come.

We cannot continue to build our future on a history that teaches us a culture of reliability and hard work as employees of foreign investors. Rather, history’s tremendous value to us must be the virtue of it teaching us the regaining of power.

This conviction that the transience of democracy is dependent solely on the input of the Eurocentric culture must be discredited and abandoned for the falsehoods it carries. Our politics, our voting patterns and the education we give to our children must all be about the African regaining power, and not about the African being endorsed as democratic by his former colonial master and enslaver.

We cannot keep voting in governments whose idea of education is a perpetuation of the colonial legacy — an education that covers everything else but the regaining of power by the African.

We cannot continue on this path of miseducating ourselves, and we cannot keep on misleading our children from one generation to the other.

It is not at all misplaced to conclude that the majority of our African political elites are miseducated and misled, often shamelessly and proudly bragging about their ability to conform to Western norms — profusely endeavouring to imitate the democratic culture of Westerners.

We must understand the emptiness of democracy in Africa’s poverty. Freedom does not exist in poverty, and without economic power there is virtually no such thing as freedom.

The illusion that an election rated as free and fair by Western observers has got something to do with freedom and democracy is quite confusing, and it is important that it is confronted.

For as long as South Africa’s ANC continues to win free and fair elections without securing economic power for the people of South Africa, there will never be such a thing as freedom for the poverty-stricken ordinary South African from the ghettoes of Soweto.

Those of us Zimbabweans who mistook the mere act of compulsive acquisition of land for economic empowerment have tragically ended up leasing acquired land back to the former white occupiers, or in many cases leaving the acquired land to lie idle and unutilised. Equally those of us who today believe that the acquisition of majority shareholding in white-owned businesses is in itself an act of economic empowerment are tragically fooling themselves.

Shares by their very nature are merely a reflection of the performance of a business, not the business itself, and share hunters masquerading as serious business-minded people must get this clearly.

The justification in the economic empowerment law that provides for compulsory majority share acquisition for indigenous people is premised on the point of view of correcting the historical injustice in the exploitation of national resources. The law seeks to end the colonial privileges of the foreign investors, and to empower the post-colonial African in the economic affairs of the country.

For sustainable development to occur share acquisition must be matched by production. Envy and greed are not business skills and must never be confused for such, even where political expediency is so tempting.

The idea of Zimbabwe’s economic empowerment programme is not exactly to increase the number of indigenous people with shares in the country’s business sector. Rather it is to grow the country’s economy in a context of local ownership of the means of production.

There is no way we are going to truly grow the economy of Zimbabwe if we are going to be electing politicians clearly smitten by the fear of imperial powers — politicians obsessed with merely making the political ballot viable, and never daring enough to provide for our people the all-important economic ballot.

The West vociferously backs Morgan Tsvangirai in the charged rhetoric about the high-sounding nobility of freeness and fairness of the political ballot.

Those from Zanu-PF who have pushed for an alternative of the economic ballot in the coming elections have zero support from the West, and without any doubt a ballot for the economic justice of our people is viewed as a dictatorial act or cronyism, even without any shred of evidence.

Tsvangirai has publicly declared that economic empowerment at the expense of Western investors is “bad crafting” of policies, and naturally there is indisputable concurrence in the West. Tsvangirai is not without African allies on this one, not least the Botswana president whose commitment at endorsing Western opinion on all African countries but his own is quite telling. Recently his Foreign Minister was declaring sanctions on Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta for “wrongly’’ winning the presidential election against the Western-favoured Raila Odinga, and that at a time everyone was waiting for a court verdict on Odinga’s court application.

We cannot endorse this thinking that Africa is only good for its labour, and surely Zimbabweans must not dignify the timidness of political leaders who cannot brave the prospect of bruising the ego of the white man — leaders like Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai who openly avoid every cost in confronting the glamour and might of Western investment.

We liberated ourselves not to spend our lives in long political discussions about the morals and equivocations of democracy however civilised this preoccupation may be regarded. Rather we liberated ourselves to seize power from the white man — that tormenting coloniser that once took away our dignity and identity. This truth is pure and simple, and there must be no apologies.

Every African leader who does not understand that independence is about regaining power in its economic and political totality is not worthy leading our people. Is it not sad that we are being coerced to commit ourselves to working so hard in proving our goodness to the white man? We hear our politicians preaching so fervently our commitment to saintly behaviour towards foreign investors, and it appears the urge to assure our goodness in this regard is shared across the political divide; or at least by a clique in Zanu-PF, too. It is not clear who this rhetoric is supposed to serve, but it is not too hard to guess.

At independence we preached far-reaching reconciliation instead of seizing power, and our leadership was quite desperate to impress the Westerner in matters of civility. We surpassed all expectations, and in South Africa we even went as far as celebrating an event where Nelson Mandela shared the Nobel Peace Prize with his jailer. That saintly behaviour created a revered hero in Mandela, and we are told there will be no other as great as him. We continue to hail the white skin as a symbol of sophistication and civilisation, and we highly honour and respect our white folks more for the skin they wear and less for the substance they carry.

It is plainly foolish for us to consider Africa liberated when we continue to educate our children so all they can do is to compete among themselves for employment provided by foreigners with economic power — the very people we foolishly think we liberated ourselves from.

The war against African poverty is not going to be won by securing degrees and training to do high-paying jobs.

Poverty is eradicated by creating employment and not by hunting for jobs. Those in the policy framework of the continent must get this very clearly.

We must not be so optimistic as to be stupid. Prosperity lies in economic power and not in the virtues of liberal democracy, nor in the appeal of individual politicians.

Power is not a privilege but our birthright. It is not a prerogative of politicians or their parties.

Our land and our economy are no prerogatives of any of the political parties in the country and, as such, the two come first before anything else.

As we march towards this year’s watershed elections we must remind ourselves of the true meaning of liberation. With land in our possession and the economy in our control we will feel good for something.

With the nobilities of democracy endorsed by our Western superiors we risk to die feeling good for nothing.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

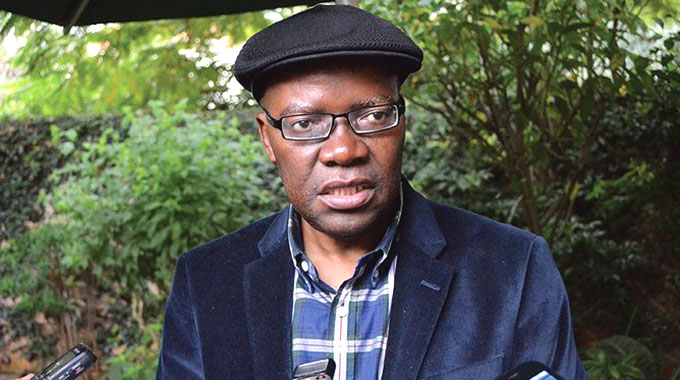

l Reason Wafawarova is a political writer based in Sydney, Australia.

Comments