Fanon, race and the power triangle

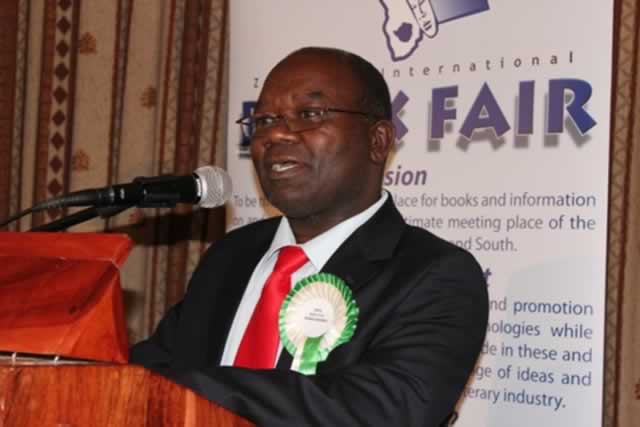

Stanely Mushava Literature Today

For Fanon, underdevelopment in Africa is not exclusively a problem of race but equally a problem of class.

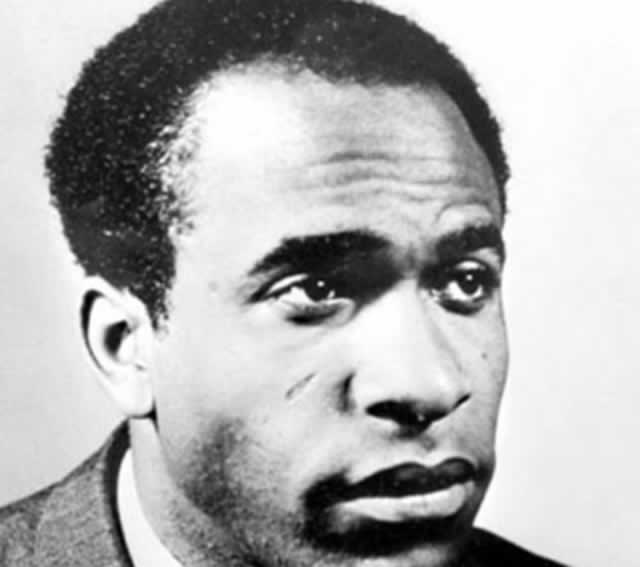

Frantz Fanon: Philosopher of the Barricades

Author: Peter Hudis

Publisher: Pluto Press (2015)

ISBN: 978 07453 3630 5

Frantz Fanon’s crusade against the shady tendencies of power crosses racial and ideological bounds.

His foremost accomplishment is, perhaps, the precedence of humanity over ideology in his work ethic.

For this, his intellectual strivings remain audible long after the curtain of history has fallen over transitory arenas and disbanded convenient alliances.

Fanon deploys moral eloquence and revolutionary fervour against racism, alienation and imperialism with a precision ahead of his time.

With inequality and racism once again emerging among the defining questions of our time, the spectre of Fanon seems bent to stalk the public square much longer.

Peter Hudis discusses the contemporary implications of Fanon’s ideas in his 2015 book, “Frantz Fanon: Philosopher of the Barricades”.

The critical biography makes the essential Fanon accessible to the ordinary reader and engages a range of scholarship on the revolutionary, while making a connection to the present.

In December 2014, a rehashed Frantz Fanon quote lit up social media as a dissenting meme after the courts acquitted a white policeman accused of murdering a black teenager.

Hudis opens his book with the episode, in which tens of thousands Black Lives Matter activists poured into the streets, declaring with Fanon, “We can no longer breathe,” to illustrate that Fanon is alive and relevant in today’s agora.

For Fanon, racism is not a biological condition but the product of political structures, not a remote abstraction but evident in social and economic conditions, not past remedy but where it persists, conflict is inevitable.

“Still, the fact that Fanon’s words were quoted a bit out of context – a problem that has arisen repeatedly since his death in 1961 – is less important than the fact that his ideas are seen by many to speak to the urgency of the moment,” Hudis observes.

“That the moment we are living through is urgent is clear – and most of all to blacks and Latinos in the US, as well as immigrants from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East facing heightened police abuse and racial and religious discrimination throughout Europe.

“Time seems to be marching backward in many respects as xenophobic – as well as subtler but no less insidious – forms of racism seem to define the very shape of globalised capitalism in the 21st century,” he contends.

For Hudis, Fanon’s incisive critique of racism is necessary for shape-shifting today’s hate-riven societies.

If Fanon’s dark prognosis of the post-colony in relation to the imperialist establishment leaves no room for a sunny outlook, it is because he pursues the problems of race and power to their logical conclusions.

Hudis argues such an approach is the condition for optimism because racism cannot be decisively dealt with outside the knowledge of its extent and potential.

The darker the prognosis, the more potent the prescription: hence the case for Fanon’s resurgence.

Fanon’s philosophical influences, or rather correspondences, for everything is mediated to fit the African reality, are brought to life in the biography.

Sartre’s “Being and Nothingness” Hegel’s “Phenomenology of the Spirit” and Mannoni’s “Prospero and Caliban”, all received against an insistence that every idea has to justify its currency in the context of lived experience, are of particular interest.

Fanon probed the problem of race in light of its socio-economic trappings, a method still pertinent as blacks are still the overwhelming majority at the base of the pyramid.

However, his psychiatric practice compelled him to probe the working of racism in the inner man.

“When you are judged as less than human because of the language you speak, the religious belief you uphold, or the colour of your skin, there is a breakdown in the structure of mutual recognition,” Hudis discusses Fanon’s treatment of the idea of “Self and Other”.

“Your sense of self and dignity does not rest on you alone. It is formed and developed by being acknowledged and recognised by others. When that breaks down, you suffer a weakened sense of self, a loss of self-esteem,” writes Hudis.

Fanon’s psychiatric practice and philosophical work cross-pollinated each other and share a conscientious gene which foregrounds the oppressed, shatters walls and bares the power of its cosmetics.

The critical biography discusses Fanon’s major titles, “Black Skin, White Masks”, “A Dying Colonialism” and “The Wretched of the Earth” in light of events in Fanon’s life and the underlying current of revolution which aggregates his strivings from start to finish.

Shuttling between his revolutionary watch posts in North and West Africa, Fanon witnesses the tendency of inhumanity to propagate itself across political dispensations and ideological frontiers.

Several ironies of history stand out in this regard, overtly informing the tenor of Fanon’s intellectual strivings.

Firstly, the massacre of 30 000 Algerians by France shortly after the Second World War in which the latter supposedly fought to defend democracy and humanity against the menace of fascism.

The Free French Army was operating in North Africa during the war and Africans, including Fanon, had enthusiastically joined it for the cause of freedom.

On the threshold of a post-Nazi world, Algerians justifiably hoping that freedom will be extended to Africa found themselves being massacred, a brutal expression of France’s determination to keep its stranglehold on Africa.

Fanon was attentive to the contradiction. It went to a European conviction that all races are not being qualified for freedom, negating the cause for which nations had collaborated against the Nazi war machine.

Not long after, the socialist tendency of French politics which Fanon had warmly regarded endorsed the country’s atrocious retaliation against the liberation movement in Algeria. Over a million Algerians were killed.

Again, race was central to the contradiction. The socialists of imperial Europe, ostensibly fronting an international class struggle, could play down their own core message and let racism lead when it came to Africa.

Fanon, however, refutes a tendency current among other writers to deploy race as a principle of moral judgment.

The quest for power for its own sake within liberation movements, the emergence of totalitarianism and plutocracy in liberated Africa and the readiness with which many leaders made their nations vassals of European neo-colonialism in return for an easy route to independence are sites of disillusion.

The betrayal, hypocrisy and atrocities that inundated the former side of history have made their way into independent Africa and Fanon is unsparing in his assessment of the nationalist bourgeoisie.

“For the bourgeoisie, nationalisation signifies very precisely the transfer into indigenous hands of privileges inherited from the colonial past,” Fanon writes.

For him, underdevelopment in Africa is not exclusively a problem of race but equally a problem of class.

He perceives a power triangle whereby the long-suffering African majority has not only the millstone of global capitalism and imperialism to saddle but also an indigenous elite which values profit and power over people.

Fanon has few equals in his penetrating critique of power, but I take exception to his fetishising violence as the only way to self-actualisation and negation of the African past bordering on the postmodernism.

“Frantz Fanon: The Philosopher of the Barricades” is an intelligent reconstruction of one of the developing world’s foremost thinkers.

Comments