Economic transformation: lessons from forerunners

Rudo Grace Gwata-Charamba Correspondent

In the present-day increasingly competitive global economy, the achievement of a change in development status calls for continued meaningful economic growth, which has to be earned rather than be taken for granted.

At the same time, historical drivers of such growth have become awfully unreliable for delivering strong economic outcomes, thus mounting pressure on stakeholders, particularly governments, to select and use of highly effective strategies.

Economic transformation, a comprehensive and structured long-term process involving the implementation of several reforms in synergy, has proved to be one such highly effective strategy in several nations.

Its interim goals incorporate rapid economic growth, reduced poverty, more equality and increased access to services.

This entails a shift of the economic fundamentals from a traditional, low productivity base and lower income status to a more industrial, diversified, high productivity and higher income status.

The transformation programme ordinarily spans over decades and is characterised by greater international integration, increased investment and savings, a stable macro-economic environment, a commitment to market-driven processes for resource allocation and paying close attention to environmental issues.

For example, Malaysia successfully transformed from an agricultural and commodity-based low-income economy to a middle-income economy and, since 2010, is aiming at a high-income nation status by 2020.

For that reason, it is recognised internationally as a model of national socioeconomic transformation. Similarly, in the year 2000, Rwanda crafted its roadmap, comprising a series of 5-year development programmes, for reaching middle-income status by 2020.

With an economy currently ranked second fastest growing in Africa, it is also the most improved nation in human development in the world.

A “developmental” state, characterised by transformational leadership and the possession of an appropriate vision and adequate capacity for prudent management of the economy, is essential for shaping the transformation agenda. It clearly demonstrates full commitment to pursuing sustainable and inclusive transformation typically through effecting long-term changes in infrastructure, industries, technologies and institutions that are integral and profound enough to be sustainable.

However, people are generally uncomfortable with change and will always attempt to resist it, thus compelling leaders to take tough measures, often against the status quo, and prescribing focused intervention to solve problems as well as accelerate progress.

Literature shows that the associated transformational leadership often entails significantly disappointing people so as to help them realise substantive benefits thereafter.

In the same context, key institutions are set up or revived and empowered to enhance the productivity and competitiveness as part of transition into an economy based on high-skilled labour, knowledge and innovation.

Such empowerment is mostly achieved through the design and implementation of appropriate skills development programmes as well as the re-orientation of educational curricula to market priorities.

In fact, experiential evidence from several nations shows that continued reliance on readily available low-cost, low-skilled workforce hinders economic transformation. This underscores the need for sizeable investment in human capital.

Although there is often consensus on the direction and some fundamentals of economic transformation, there is no standard model for success. Nonetheless, there are several similarities and key lessons identified in literature, particularly from some Asian countries that have proved to be effective in varying environments and thus likely to be useful in the implementation of the transformation programme in Zimbabwe.

To drive a sustainable and resilient economy, governments are generally compelled to craft tough fiscal policies rather than stick to popular tradition. For example, in Malaysia, subsidies were cut, a Goods and Services Tax (GST) imposed, policies implemented to enable a friendlier business environment for the private sector to flourish, elements that caused outcry.

However, after the demonstration of initial results, stakeholders eventually began to adapt to the new realities, while expecting positive trade-offs for the opportunity costs.

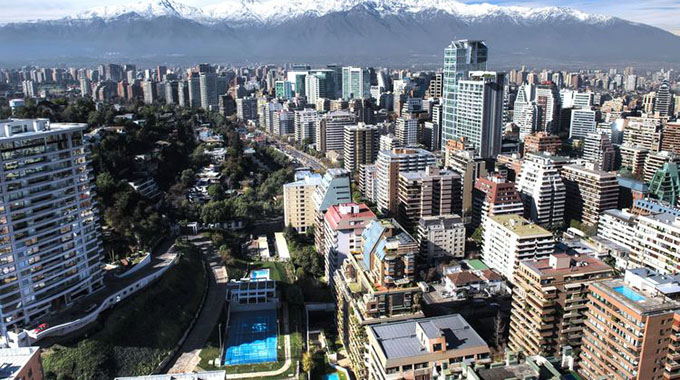

Chile’s economic transformation programme, another success story, spanned over more than 30 years with a crisis period in between. Likewise, economic transformation programmes for some fast growing East Asian economies spanned one to two generations, while the Rwandan success story emanates from Vision 2020 that was laid down in the year 2000.

According to a former Minister of Finance in Chile, the crisis atmosphere had positive elements associated with it despite its negative perspective.

It generated a sense of urgency for change, while the implications of not reforming were better understood, thus driving concerted effort that included the mobilisation of capable teams which effectively achieved the required changes to sustain reforms towards transformation.

In the same context, the leadership at all levels gave up personal ambitions and acted for the benefit of all stakeholders.

Additionally, hundreds of collaborators made personal decisions to devote themselves entirely to the task of reform despite the availability of more favourable options.

Subsequently, all groups emerged from the crisis conditions with a sense of mission.

Nearly all success stories of economic transformation revealed that fundamentals that encompass unity of purpose, hard work, dedication and support from allies significantly impacted on the achievement of interim goals and also helped to overcome implementation challenges.

That is, most successful economic reform initiatives were the product of hard work and the concerted efforts of a number of stakeholders encompassing individuals, groups and organisations aiming at a common goal.

Experiential evidence from Chile shows that it is critical for all stakeholders to understand that economic transformation processes do not belong to a specific group, political party or even a government. Instead, sound economic policies are everyone’s policies and constitute part of the national agenda.

According to one of the former Ministers of Finance, such understanding led to rational behaviour that defended reform efforts rather than attempt to destroy them through political processes as experienced earlier. Consequently, the concept of opening Chile to the international economy and becoming part of the globalised world was generally assimilated into the national culture correspondingly, the ownership of economic transformation programmes by a wide range of stakeholders at national level has been a key success factor in many other countries notably Rwanda and Malaysia.

The design of well-defined transformation programmes underpinned by the Results-Based Management (RBM) approach and focussing on a limited number of specific ideas and actions rather than concepts was determined to be key for success.

For example, in the Malaysian programme, there were eight national key results areas (NKRAs), 12 national key economic areas (NKEAs) and six strategic reform initiatives (SRIs), all of which were successfully delivered.

The associated results-oriented culture and systems were characterised by their emphasis on integrated inclusiveness and sustainability, the use of highly participatory processes, rigorous performance measurement as well as continuous learning and improvement. Participatory processes entailed incorporating stakeholder input into planning, performance assessment and process adjustment. Lessons from both success and failure were effectively used to shape decisions.

In fact, the people-centred development expertise in the context of a pervasive results-oriented culture was determined to be Malaysia’s major strength and key success factor. Moreover, implementing the Rapid Results Approach, which entailed the effective implementation of Rapid Results or 100-day Initiatives, was also the norm in most success stories.

In general, the invisible hand of markets often proved insufficient to ensure the transformation of economies, particularly on issues regarding the overall macro-stability and the need for a regulatory system favourable for private sector investment.

Accordingly, governments played a proactive role in facilitating and accelerating the process of economic transformation, with particular attention to issues of targeting and prioritisation.

That is, apart from the general incentives and securing a stable business environment, governments also methodically identify priority sectors in which to improve sector-specific infrastructure.

Such a central role of the State was reaffirmed in its contribution to the economic success of most Asian as well as some Latin American countries.

A significant lesson from Malaysia was that the sustainability of economic transformation programmes ought to be in both economic and environmental terms, where growth is achieved without exhausting the country’s natural resources.

This calls for governments’ commitment to the stewardship and preservation of the natural environment and non-renewable resources. Furthermore, it was determined that transformation could not be achieved simply through the income derived from extracting natural resources, but also required a sustainable fiscal policy with added focus on investment led by private sector.

Furthermore, cultures that fostered growth as well as value, admire and stimulate their entrepreneurs habitually attained critical momentum in the development competition.

This was exemplified in Chile where opening to the global economy and revitalising the private sector were key success factors.

The appreciation of entrepreneurial activity was incorporated into the national culture, a factor that enhanced the competitiveness and prosperity of business enterprises on both the domestic and international markets.

Again, according to literature, a significant number of nations relied on home-grown and often unconventional, policies and initiatives for their transformation programmes.

The strategy created buy-in and ownership of the processes among a wide variety of stakeholders who also jointly designed solutions to identified challenges.

This was in line with the growing recognition that local solutions to social and economic problems have a more significant and longer-term impact than those from other locations.

For example, Malaysia used the innovative concept of “Labs” which are innovative consultative workshop processes where people work together iteratively to design solutions to identified policy challenges within a strict timespan.

Likewise, development leaders in Rwanda report the adoption of innovative home-grown solutions implemented across key sectors. This includes community work (Umuganda), performance contracts (Imihigo) and the Gacaca (traditional way of resolving conflict). A key message that emerged from most success stories was that the use of such solutions calls for the creation and development of a strong platform for communities to engage decisively on all development issues.

Besides the best practices, there were also several lessons learned from negative experiences in transformation processes.

Most prominent among these lessons was that although the effects of good policies are far-reaching, many countries continually adopted misguided policies that appeared to favour the poor on the surface when, in fact, they had grave shortcomings.

This was mostly because the policies were ill-conceived or driven more by pressure groups than the needs of majority stakeholders. Comparably, several well-inspired reform processes, especially in Latin American countries, failed because of partial plans that lacked understanding of the main challenges of the associated economies.

Another major shortcoming was the failure by many nations to foster a culture that underscores the value of entrepreneurial activity. In contrast, there was a common theory which wrongly stressed that the fate of workers can be changed by simply changing a law or strong regulations. Regrettably, experiential evidence from many countries showed that in reality, it takes a dynamic economy, created over a long-term, to continually create and improve jobs.

Also, fewer regulations facilitated the presence of more entrepreneurs and more competition on the market; a situation that afforded consumers access to a wider and cheaper assortment of goods. Another similar widespread belief, which is yet to be confirmed, was that state policies protect and help companies to grow.

In essence, great and common lessons, particularly from the forerunners of economic transformation include the long-term nature of the process as well as its demands on key stakeholders.

It is accomplished through the continuous implementation, ordinarily over decades, of a number of reforms in synergy while consistently focussing on the targeted results.

In addition, the process calls for unity of purpose, patience, resilience and determination among stakeholders, in shaping their development.

Overall, the whole transformation process should be inclusive and democratic enough to ensure buy-in and ownership by a broad spectrum of stakeholders.

These lessons may prove to be helpful for purposes of both encouragement, learning and adaptation in Zimbabwe as the nation implements its own transformation programme towards achieving Vision 2030.

Dr Rudo Grace Gwata-Charamba is an author, project/ programme management consultant and researcher with a special interest in Results-Based Management (RBM), Governance and leadership. She can be contacted via email: [email protected]

Comments