Childhood TB: A cause for concern

Rumbidzayi Zinyuke-Health Buzz

Children the world over remain under-reported victims of tuberculosis (TB) as the majority of cases still go unidentified despite the disease being curable and preventable.

TB is one of the leading causes of death in many countries, particularly in Africa, with children less than 15 years of age accounting for up to 20 percent of people infected by the disease every year.

Statistics show that more than 60 percent of all children with TB are never diagnosed with the disease and 96 percent of children who die from TB are never put on treatment. About 80 percent of them are younger than five years old.

In 2020, 59 percent of people developing TB globally were diagnosed and treated, but the figure for children was significantly lower at 37 percent, indicating that children face more barriers to accessing TB care compared to adults.

This is the case for Zimbabwe where only six percent of childhood TB cases are being diagnosed and put under treatment.

According to information from the National TB programme, children should account for at least 10 percent of the total TB cases in the country but this has not been the case for years.

This means there are many children with TB who are not being identified and will not get to receive the life-saving treatment that is available for them.

Although Zimbabwe has been reducing the burden of TB over the years, there is a gap between the TB incidence and the TB cases actually being picked up.

In 2021, about 12 000 cases were missed, and of this number there was a significant number of children.

This becomes a cause for concern.

It is imperative that the missing people be identified so that everyone with TB is diagnosed early and is put on treatment.

More so for children, because they are more difficult to diagnose. Hence early identification will help to avoid morbidities and deaths due to the disease.

Young children are at particular risk of TB as their immune system is still underdeveloped.

The risk is compounded by factors such as poverty, malnutrition and other immune suppressing illnesses such as HIV.

There are several reasons why it is hard to confirm the diagnosis of TB in a child.

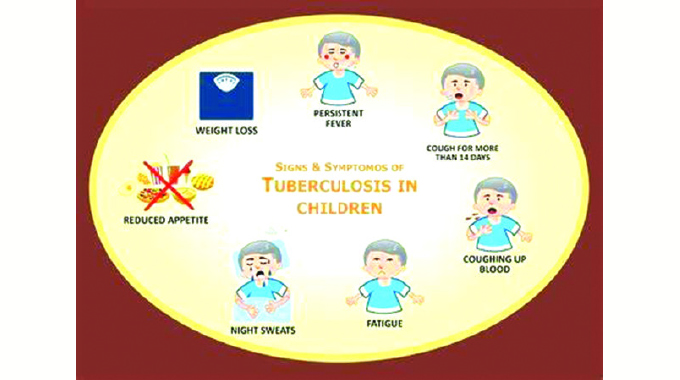

According to experts, the clinical presentation of a child with TB is often different than for adults.

Children have more non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, fever or slow weight gain, especially in malnourished children.

This leads to misdiagnosis and children may be put on treatment for other diseases, instead of TB. The affected children will miss out on the treatment they actually need.

Children also become sick with much lower levels of TB bacteria compared to adults, so when testing, it is possible that machines can fail to detect the low levels of TB bacteria, and the child does not test positive for TB.

Another important difference is that children, unlike most adults, often have TB infection outside the lungs, for instance in lymph nodes or bones where it is difficult to collect samples to test.

This all adds up to the devastating situation that the majority of children with TB are never diagnosed, and only a minority have a positive test that confirms the disease.

With TB, as with all diseases that impact children, an early and accurate diagnosis is vitally important for them to be put on to lifesaving treatment as soon as possible.

But because the majority of children who fall ill to TB are younger than five years, it becomes less and less possible.

In 2020, it was noted that the profile of childhood TB patients indicated that at least 60 percent of them were in the 0–5 years age group.

This is because children in this age group have an undeveloped immune system, therefore, they are at a higher risk of developing active TB if exposed and infected with TB.

Furthermore, children in this age group spend prolonged periods of time in close proximity to their caregivers; therefore, they are at a high risk of contracting TB if their caregiver is suffering from the disease.

Acting director in the Ministry of Health and Child Care AIDS and TB unit Dr Fungai Kavenga confirms that it is difficult to test TB in younger children.

“Commonly, we expect the patient to cough up the sputum for testing but young children are unable to do that and this makes it challenging for the health worker,” said Dr Kavenga.

The World Health Organisation last year released updated guidelines on the management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents which sought to address some of these gaps in case identification among children.

The global health body recommended that children who cannot produce sputum can also be tested for TB using stool, which makes it easier to pick up cases.

Dr Kavenga said Zimbabwe, after doing research, was now able to use stool to diagnose TB in children.

“This is an important intervention being rolled out to all our districts so that children can access TB testing. But as with all diseases, prevention is better than cure. And TB is preventable,” he said.

The BCG vaccine is used to prevent TB and it is more effective in children, but its efficacy in adults is inconsistent.

Zimbabwe has been administering the BCG vaccine to babies soon after birth as part of its routine immunisation schedule.

But according the WHO, while childhood vaccination against TB is critical, the BCG vaccine has limited efficacy against other forms of TB.

The health body says vaccinated children were shielded from contracting the most severe forms of TB (meningitis and disseminated TB disease) but they were not protected against contracting it from an infectious person.

This means there is still a lot to be done to ensure that children are protected from this disease.

Combating childhood TB is one of the WHO ‘End TB’ strategies and TB preventive treatment was one of the targets set by the UN high-level meetings on TB from 2018-2022 aiming to reach 30 million eligible people with TB treatment by 2022.

It is yet to be seen if these targets were achieved.

But Zimbabwe on its part has huge ambitions which auger well for eliminating the threat of TB over the next three years.

Through the National TB strategic plan, the country aims to reduce the incidence of all forms of TB by 80 percent from 242 cases per 100 000 population to 48 cases per 100 000 population by 2025.

There are also plans to have reduced the mortality of all forms of TB by 80 percent to 8 deaths per 100 000 population by the same year.

But as Dr Kavenga said, to end TB there was need to adopt new innovations, new tools, new technologies, so research is a key pillar and adoption of new technology is important for that to happen.

Maybe then people we can begin to see a real change in the reduction of the unacceptably high number of children with TB who are not identified and those who continue to die from this preventable and curable disease.

Feedback: [email protected]

Comments