Art alive, keeping tags

David Mungoshi Shelling the Nuts

For the purpose of today’s story, I am going to use a rather liberal definition of art, one to include even the letters that people write to newspaper and magazine editors.

Many years ago, when national hero Enos Nkala was Minister of Defence, a prankster wrote him an open letter through the Chronicle of Bulawayo.

Whether the prankster had borrowed the idea from someone else or not is, for my purpose, immaterial.

I remember seeing the letter and thinking how so very original it was and how hilarious as well.

Like all letters, this letter had a salutation: Dear Minister Nkala. After the salutation there was blank white space at the end of which the writer had signed off: Yours faithfully, The silent majority.

Obviously, the writer had some gripe with the minister, but whatever the case was, when we look back critically, we can salvage a few pointers regarding the state of the nation at the time.

Clearly, art does reflect on society and it does keep tags on what may be happening at any given point in time.

Zexie Manatsa

Not too many people are aware of the fact that tiny Lesotho is completely surrounded by the Republic of South Africa.

This has always meant that Lesotho’s foreign policy was somehow fettered in its originality by what must always seem and feel like a ubiquitous neighbour – all powerful and all-encompassing.

In such situations, music-makers come in very handy indeed in terms of recording and capturing the happenings of an era.

During the apartheid era in South Africa, and when Chief Leabua Jonathan was Prime Minister of Lesotho, something that (had blood not been thicker than water) really ought to have been the subject of an international inquiry happened.

The incident happened at a time when there was great tension between Maseru and Pretoria. As a result of the tension, South Africa blockaded Lesotho and cut off its supplies of essential food material.

Chief Jonathan then arranged to have a cabinet meeting far from the madding crowd, somewhere in the mountains. The idea was to deliberate over the impasse with Pretoria.

But as things happened, eight cabinet ministers travelling to the rendezvous perished in an orchestrated shooting incident.

Each of the eight had taken his wife along and only one of the women survived to tell the story. This is the calamity that Steve Kekana sings about in his 1981 release, “Kodua ea Maseru” (the calamity in Maseru).

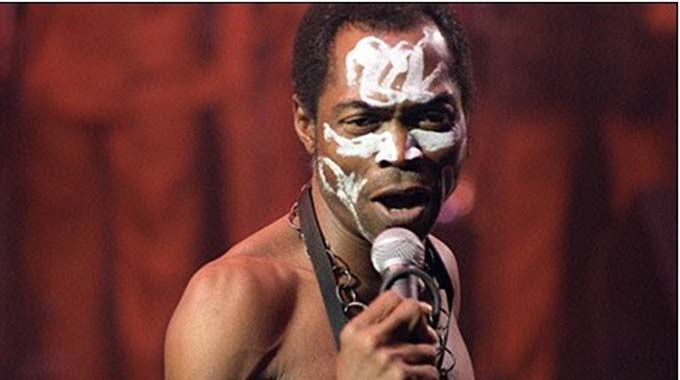

The epic battles between Fela Kuti the Afro-jazz maestro of Nigeria and the authorities there is well-documented.

Fela’s politics was wide and scathing and spared no-one. His roving eye and artistic genius were deliberate and honest in his portrayal of the woes of Nigeria in particular and Africa in general.

Fela was an intellectual and could have become a medical doctor if had not, instead, opted for music.

In “Lady” his classic hit song, Fela turns social critic and laments the loss of African values and the emergence of a woman who “go dance the lady dance”, smokes cigars and must sit at the head of the table and help herself to the meat before anybody else does.

This lady cannot do the fire dance. She’s too refined for that, Fela’s compliments are a scathing tongue-in-cheek attack.

In “Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense” Fela spells out his view that the teacher is not only the one we find in a formal classroom.

There are many types of teachers depending on the situation: the classroom teacher, the university lecturer, government, father, mother and so on.

He goes on to attack models of political economy such as that left behind by Africa’s erstwhile colonisers and some of Nigeria’s modern crop of leaders, including Olusegun Obasanjo and Shehu Shagari.

In the line “Let us face ourselves for Africa”, Fela appeals to Africans to face the continent’s problems firmly and squarely. His stance is essentially Pan-Africanist.

Today Fela is honoured annually with the “Felabration” week, which is a vindication of his life and work.

Nigerian authorities at the time chose to see him as a rabble-rouser and took measures to silence him through imprisonment and by attacking his compound.

Fela’s mother subsequently died from the injuries she sustained when soldiers attacked her son’s compound popularly-known as the Kalakuta Republic.

Kalakuta was the communal compound that housed Fela’s family, his band members and a recording studio.

In “Kalakuta” Fela gave a satirical and indigenised rendition of the name of the prison cell he was held in. For some reason, the cell had been named “Calcutta”.

Elsewhere, other musicians have also been true to their art and used it as the ear and eye of the people.

“Why Lord, Why?” by Brook Benton was banned in Rhodesia for its commitment to non-racialism and for its attack on white supremacist views.

The line that says, “The colour of my skin is said to be an awful sin” was probably too much for the Smith regime and the song was proscribed.

In “Heaven Help Us All”, Brook Benton does a no-holds-barred song.

Its lyrics are a lamentation as well as a prayer:

Heaven help the child who never had a home,

Heaven help the girl who walks the streets alone

Heaven help the roses if the bombs begin to fall,

Heaven help us all.

Heaven help the black man if he struggles one more day,

Heaven help the white man if he turns his back away.

Heaven help the man who kicks the man who has to crawl,

Heaven help us all.

Heaven help us all

Heaven help us all, help us all.

Heaven help us, Lord, hear our call when we call Oh, yeah!

Heaven help the boy who won’t reach twenty one,

Heaven help the man who gave that boy a gun.

Heaven help the people with their backs against the wall,

Lord, Heaven help us all.

This song is as militant as they come, and must probably have endeared Benton with all black people familiar with the song. Because the lives of black people around the world continue to be deprived and generally oppressed, “Heaven Help Us All” continues to be relevant and poignant.

You look at some of the goings-on around the world everywhere and cannot help but sing along, “Heaven Help Us All.”

Take for instance, the sanctimonious stance of former apartheid stalwarts in South Africa. While remorse and repentance are commendable, one gets the impression that many of the people who now vilify apartheid only do so because it is currently the politically correct thing to do.

It would be a lot easier to believe the copious crocodile days from some of our white neighbours if they could be seen to be doing sizeable philanthropic work aimed at making sure that all children always have a home and that the black man never has to struggle again.

America owes it to the world to rein in the erratic Donald Trump, who if allowed to flourish, might cause a world calamity by triggering a nuclear war which he cannot possibly win.

What is even more disturbing is Trump’s endorsement by clueless black celebrities like Kanye West.

The Uncle Tom syndrome so vividly rejected by Muhammad Ali is, regrettably, alive and well in the fabled land of freedom and opportunity where people who should know better “big-up” a racist like Trump.

Leonard Cohen was justified in asserting, “Democracy is coming, to the USA.”

The music and lyrics of Bob Marley stands out and has done so for a long time now. What with songs like “War” and Others”.

In our own region, musicians have consistently sung about our times. They have done so through their lyrics and through their songs.

Dorothy Masuka composed the popular “Khawuleza” song that aptly depicts the cat-and-mouse game between township dwellers in Alexandra, Soweto and other places and apartheid South African police. And Hugh Masekela in his song “Stimela” (The Coal Train) is even more explicit:

There is a train that comes from Namibia and Malawi

There is a train that comes from Zambia and Zimbabwe,

There is a train that comes from Angola and Mozambique,

From Lesotho, from Botswana, from Swaziland,

From all the hinterland of Southern and Central Africa.

This train carries young and old, African men

Who are conscripted to come and work on contract

In the golden mineral mines of Johannesburg

And its surrounding metropolis, sixteen hours or more a day

For almost no pay.

When the history of our region is re-written, its works of art will be paramount and instrumental.

Here in Zimbabwe, with the new openness and the declaration of war against corruption, Thomas Mapfumo’s mega hit, “Corruption” can help expose the ill-practice and has lost neither its gloss nor relevance.

Zexie Manatsa and Oliver Mtukudzi are revered commentators on Zimbabwe’s armed struggle too. Younger crooners like Jah Prayzah have also come on board as social commentators.

David Mungoshi is a writer, editor and social commentator.

Comments