Anti-corruption – reality or rhetoric?

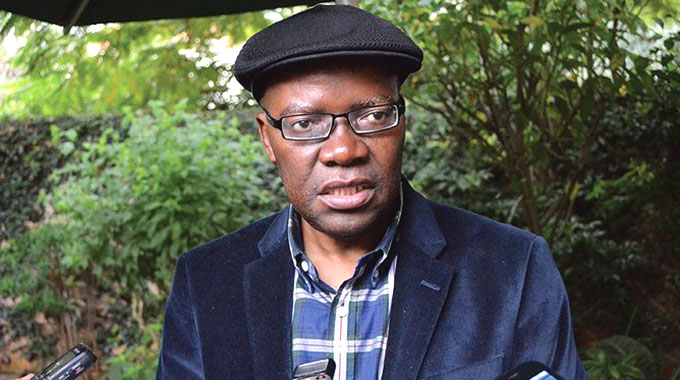

Reason Wafawarova on Thursday

The editor of this paper recently paused a question, “The fight against corruption, is it real or rhetorical?” I quickly made a commitment to write on this topic, and I even promised to borrow the topic as is, which I almost did, in my own different way. I will try to be as apolitical as I possibly can, if only to keep the focus of the reader on the main tenets of the topic at hand, which to me is a life and death matter for the nation of Zimbabwe. Corruption, however defined, affects every nation in the most negative of ways, and Zimbabwe is not an exception.

There was a time we Zimbabweans used to be shocked by traffic police roadside corruption in Botswana and South Africa, and we used to wonder how on this planet a police officer could utter a word to solicit or demand a bribe from a motorist. It was unheard of in Zimbabwe those days. No need to mention, Zimbabwe has since overtaken Botswana and South Africa’s corruption, and this could be by as much as a hundredfold.

We have no credible legislative framework to deal with the current crisis, and as things stand at the moment we badly need urgent public sector reforms, if we are going to tame the corruption monster.

We saw the self-serving approach of some of our institutions when our own police force responded almost violently (against the Press) to allegations that game rangers and members of the police force were part of a scandalous corruption ring poisoning our elephants for illegal ivory trading.

The minister responsible has since confirmed the involvement of rangers, and even after that our police force has done nothing to go after the said rangers, absolutely nothing. Instead they have dragged three journalists to the courts in an apparent silencing endeavour.

There is need for a non-partisan blueprint for fighting corruption. We cannot trust one party to deal with this national menace when it is generally believed that members of the same party are part of the problem, and not without a reasonable semblance of justification.

The document must come up with a national consensus on the causes and effects of corruption, in absolute and quantitative terms. We must also come to understand the reasons for past failures to deal with the scourge, even after countless political declarations that corruption would not be tolerated.

Clearly corruption in Zimbabwe is more than tolerated, and any counterview is simply myopic.

Caesar Zvayi, the Editor of this paper, also asked me to say whether or not we can have a commission of inquiry as successful as the Sandura Commission of the late eighties. In this context we must also try to find the reasons for the past success, and why the successes have been hard to replicate. We do not need another Sandura to have similar success. Rather we need the environment under which Sandura and his colleagues carried out their mandate.

Above all, we need concrete actions on how the country is going to deal with corruption, not impressive individual declarations by excitable politicians whose only aim is to impress their listeners. We have heard a lot more than enough of this kind of nonsense, like “Minister so and so vows to deal with corruption.” What we need now is to address the how part of the question. We are better off spared the media rhetoric.

Our civic society, political parties, analysts, and anti-corruption campaigners must focus on the implementation of anti-corruption laws and statutes. If they did, a volunteer whistle blower like Munyaradzi Kereke would be enjoying a lot of support, or at least co-operation in the allegations he is making in regards to alleged corruption at the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe during his tenure at the institution. The man repeatedly says he has evidence, and no law enforcement agency seems interested.

Neither the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission nor the police seem interested in the matter, and that is quite telling. More worryingly, the civic society is also reticent on the matter. The man could be driven by vindictiveness, but he still raises serious allegations that need to be investigated without fear or favour, at the very least.

It is sad that our civic society would rather focus on the endless debate of what is corruption, what it should be, and what it is not, and we have seen endless talk shows and workshops on this unhelpful rhetoric.

The vacuous and repeated statement that Government has a zero tolerance policy on corruption is now an insult to our people. We all know that there is no such policy in place, except on the lips of those who have enjoyed uttering it.

There is a globally recognised three-prong approach to fighting corruption, and it rests on tripartite pillars; prevention, education and enforcement. The education bit includes public awareness, and the enforcement bit is all about investigation and prosecution.

Unless we put systems in place to seal the loopholes, we cannot meaningfully talk about eradicating corruption in Zimbabwe. In order to get to the point where there is enough willpower to fight corruption there must be enough awareness about its negative impact. There is need to quantify the damage inflicted upon our people by the scourge of graft.

Only after such awareness has been created can we create a collective resolve for the people of Zimbabwe not to tolerate corruption.

It was pleasantly refreshing to see one very patriotic Zimbabwean by the name Tendai Jongwe posting some images on social media of an alleged corrupt traffic police officer who had been confronted by passengers from a commuter minibus, after she reportedly solicited for a $10 bribe from the bus crew, all in the full view of the 18 or so passengers.

We need more of such public anger against corrupt officials, if not nastier. Public intolerance and fury must be thoroughly encouraged as a deterrent for would be corrupt miscreants. We have to ensure that people will think twice before they can entertain even the thought of corruption.

Prevention means opportunities for corruption are reduced, and that is very important. The first step to be considered is public sector reforms. The Auditor-General’s Office, the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission, and the leadership of the police force all need a complete structural overhaul if corruption is to be tamed.

We need to enforce a strong and effective asset disclosure regime, and there must be no loopholes on this one. When a minister responsible for local government is reported to have huge tracts of land and hundreds of properties across the country alarm bells must ring, just like when a minister running the Health Ministry suddenly has a series of private clinics across the country.

It is important that members of the public service earn acceptable income; otherwise the temptation to engage in corruption will remain high. Environment Minister Oppah Muchinguri asserts that the rangers poisoning our elephant herd are partly driven by want, because their earnings are currently pathetically low. That is a lame excuse from a moral and legal point of view, but perhaps an economically realistic one.

There is need to promote and enhance integrity among public office holders, and incentives to encourage good behaviour must be put in place. In the past we had public servants that were driven by the integrity of serving the nation, and they used to compete for integrity awards. That can be revived in a very short period of time, if we plan and implement proper strategies appropriately.

We can put in place and enforce codes of conduct as a way of preventing corruption. This includes enforcing conflict of interest rules, them being the most violated of regulations within the civil service.

It cannot be normal for a Mines Minister to own and run mines in his personal capacity, or a Health Minister to do private business with the Health Ministry or any of its subsidiaries. It is important that we put in place transparency and accountability principles, like access to information and effective and safe whistle-blowing mechanisms.

Public awareness is key in the fight against corruption. With adequate awareness on its part the public will become the chief policing agent. It is only in a rotten society that the public will haplessly watch acts of corruption being carried out in broad daylight, like what happens in most African countries, Zimbabwe most emphatically included.

For the public to become the chief policing agent it must be, there must be such public education as to foster awareness on causes, costs and ramifications of corruption. The idea is to strengthen the citizen’s resolve to resist, condemn and report corruption. This hopeless idea of seeing corruption happening and saying, “it’s none of my business” is not only unpatriotic, but also dangerously destructive.

In countries where the public has zero tolerance on corruption, exposed culprits often commit suicide, and that is not exactly a regrettable predicament, sad as it may be for those that happen to have parented the thieving deceased, and perhaps to those who hold humanity above its moral expectations.

To complement prevention and education we obviously need enforcement, and frankly our law enforcement agencies are doing next nothing in terms of investigating and prosecuting those people benefiting from corrupt activities.

We often hear the rhetoric about the declared resolve to investigating and prosecuting with no regard to one’s station is society, but the reality is that there are many in our midst whose standing in society is a deterrent for law enforcement – those who can criminalise and persecute anyone who may dare mention their corrupt deeds.

We need strong institutions that have the power, capacity, and authoritative strength to investigate and prosecute without fear or favour, and with full state protection. Added to this, Zimbabwe needs an independent Anti-Corruption Court with financial, political and legal independence.

If we are ever going to reach the milestone of building enough capacity to deal with corruption, we will need a lot of political will and support, not the electioneering rhetoric of charlatans.

The only reason the Sandura Commission was a resounding success was because the Commission had the full independence it required to tackle the scandal that had happened, not exactly because members of that Commission were too sophisticated to be stopped.

Zimbabwe we are one and together we will overcome. It is homeland or death!

REASON WAFAWAROVA is a political writer based in SYDNEY, Australia.

Comments