‘All I wanted was to avenge my father’s humiliation’

Phylis Kachere The Interview

The liberation struggle was an epic historical period in which thousands of freedom fighters and ordinary citizens coalesced to confront the white minority regime.

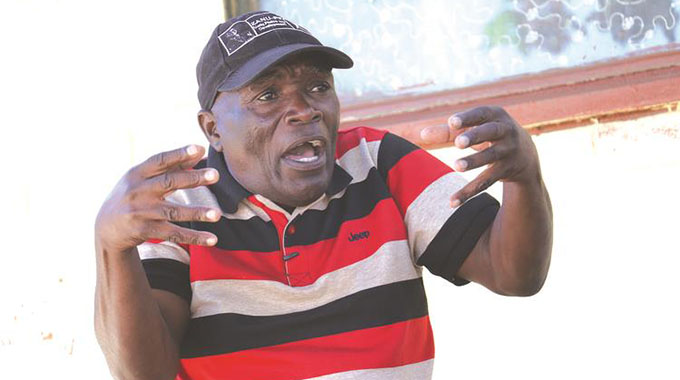

As expected of any historical epoch, the narration of that ostentatious period remains a contested and contentious terrain with multiple accounts coming from ex-combatants. In an attempt to get a deeper understanding of the war, commonly referred to as the Second Chimurenga, The Herald published a riveting account of one Cde Christopher Makwambeni whose Chimurenga name was Cde Chapwititi Chehondo. He has of late become the ‘‘posterboy’’ depiction of the combatants’ indefatigable spirit of the struggle as shown by an AP video repeatedly shown during Independence and Heroes Day commemorations. Further to the story published in The Herald of April 23, 2020, our Deputy News Editor — Convergence — Phyllis Kachere (PK) had a conversation with Cde Chapwititi Chehondo (CC) in which he sheds light on a number of issues that happened during the tension-filled ceasefire period leading to demobilisation and first majority elections.

PK: Cde Chapwititi, what motivated you to join the liberation struggle?

CC: My father used to work in the tea plantations in Chipinge as a builder and every time I would watch him being humiliated by his white bosses. Sometimes he would narrate how the white bosses always discriminated and ill-treated his fellow black workers. But the final straw was when I visited my father at his workplace intending to get school fees. I came face-to-face with his boss’ 12-year-old son kicking my father and scolding him. I did not expect that. We had been taught in the village that we do not answer back to our elders, let alone kick and scold them.

But here I was, face-to-face with such a humiliating act being meted out on my own father. The boy had the temerity to set his dogs on me and I was terribly bitten. From that day, I resolved that I would avenge my father’s humiliation and decided the only way to do so was to be trained as a liberation fighter. I just wanted to get my gidi (gun) and come back and deal with the white boy and his father. That became my motivation even when the chips were down during training.

PK: How did you reunite with your family after the liberation war?

CC: I was stationed at Tongogara Assembly Point in Chipinge in early 1980. All the combatants in the assembly point had just been given $200 each for incidentals. I decided to go home. I did not go straight to my father’s homestead. I went to my maternal grandmother’s homestead, Gogo Lina Sigauke, who lived 5km away from my father’s. This is the same gogo, whose gawu (portion of maize field) I had left uncompleted as I left for “kumabvazuva” (Mozambique for training). My grandmother cried and ululated, thanking our ancestors for keeping me safe during the war. She reminded me of my debt to her and the ancestors. I had to do my share of work on the land. She always reminded me that I needed to get land, so that my outstanding gawu work could be fulfilled.

There was an overnight pungwe of song and dance as all her neighbours and other relatives joined in celebration. The following morning, my aunt’s son, Maxwell Mtetwa came to visit. His mother, was my father’s sister. We agreed that he would accompany me to my father’s homestead. I did not go straight to my father’s house. Instead, I went to his younger brother, John Makwambeni’s homestead, just 300 metres away. Uncle John did not recognise me, but he recognised Cde Chapwititi. He knew he was looking at a combatant and I could see that by the kind of respect he accorded me; that of a victorious fighter. I asked him if he had recognised me but he couldn’t. Then I said; “Ko, zvandiri Christopher wani?” He rose and embraced me, and meanwhile my mainini, his wife, started ululating and shouting “Kristofa wadzoka kani! Kiri wauya!”

There was commotion as other relatives and neighbours trooped in to Babamudiki John’s homestead. My father, Livison Makwambeni, who was yoking his cattle heard the pandemonium and sought to find out what was going on. He came, with his hands on his back as he always did. He saw me, ran towards me and fell on my feet. I also fell down and we embraced. He touched me all over my body, as if to ascertain if I was intact. Being a strong member of the United Church of Christ in Zimbabwe (UCCZ), he invited other pastors from his church and they prayed, thanking God for having spared my life.

As had happened at Gogo Lina’s homestead, there was an overnight pungwe as people celebrated my homecoming. “Mauya comrade, Mauya, tongai Zimbabwe!” became an anthem. My mother Sithembile Sigauke, who had divorced my father and remarried came two days later and the celebrations continued. My father slaughtered a beast and gave me another live one. It was a huge thing for my father to part with two beats given the importance of cattle in an African rural family set-up. It was his utmost expression of great love. A week later, I went back to the assembly point.

PK: Did you ever meet with your father’s racist employer Mr Gee? If so, how was the encounter?

CC: A few months after my return from the war, I had the chance to visit my father at his work place. By then, he was head builder. I visited and by chance, I met Mr Gee talking to my father at a construction site he was working on at the farm. Although Mr Gee could not recognise me, I was sure he could identify Cde Chapwititi. There was a certain aura that we had as returning freedom fighters. It was easy those days to tell if one was a “comrade” or not. I could see Mr Gee struggling to offer some respect to the “comrade” in me. He politely asked who I was and I told him I was Christopher, his employee’s second son. I could see fear written all over him. He invited me into his house, to which I declined. I had resolved I had nothing to do with him. He apologised for the previous poor treatment to my father and family. I am sure he apologised anticipating an attack from me. But our party ZANU, through the leadership was already discouraging us from taking revenge. Instead, they were preaching reconciliation.

I did not agree with the concept of reconciliation, but because I am a disciplined cadre, I had to obey my leaders. I asked him where his son who had set his dogs on me was, and he told me the boy had been called up (mandatory conscription into the army to fight against the freedom fighters) but had unfortunately been ambushed somewhere in Mutoko and died. I did not feel sorry for his death. My sorrow only stemmed from my failure to have been the cause of his demise. The whites had not felt sorry for my compatriots whom they had bombed at Nyadzonya and Chimoio. I immediately asked my father to resign and stop working for Mr Gee.

PK: Cde Chapwititi, I know you have fought innumerable battles. Can you describe one that was outstanding for you?

CC: The Siya Battle will for ever remain etched on my mind as the toughest. This was between the two hills that overlook Siya Dam in Mazungunye area in Bikita. We were in battle for five hours. The previous day, I had gone on my usual early morning reconnaissance in the area. I would dress up like a school boy and scout the area, then go back to the base. Our base was located between two adjacent hills. The bigger hill provided good cover with its thicket and on the other side where the smaller hill was located, there was the entrance to our enclave. It was a perfect spot. When I went out for the usual scouting the previous day dressed like a school boy, I moved around the area with the village schoolboys on their way to school. I was almost caught by the Rhodesian forces who were also on patrol. Unbeknown to me, they were closely watching my movements. Someone had sold us out. They however let me pass but closely monitored my movements.

Around 9pm on this day, the villagers had gathered at our base for the usual pungwe where I, as the sectional political commissar, would educate the povo on the ethos of the struggle. As some villagers started leaving the pungwe after midnight to retire for the remainder of the nights, we heard startling noise as they screamed after coming face to face with the Rhodesian forces who had surrounded the base, entrapping us in the enclave. We were only eight and we quickly took up our positions.

They fired first, and we realised we had been entrapped. We fought for five hours till dawn as we realised there was no way out. They used search lights to hunt us down. Our commander, Cde Tinzwei Goronga died in my arms and I know the spot the villagers buried him. I wish I knew his real name so I can lead his family to where his remains lie. Bombardiers and other enemy aircraft hovered above. We had completely been encircled. They kept dropping bombs on us. At dawn, I told one of my colleagues that we had no way out but to open fire and escape through the enemy defence line. He was hesitant and said that my suggestion was suicidal as we were literally throwing ourselves in the enemy’s firing line. I grabbed him by the balls and told him to abide with my instructions. I fired and rolled over to the other side and the enemy returned fire. I took aim and shot one of the enemies. I told my colleague that we had to quickly make our escape as we had broken their defence line. We successfully escaped, but realised we had lost four of our comrades. We also downed two enemy helicopters.

PK: What were your thoughts on integration? How easy was it for you to integrate into the army?

CC: Having been selected to be part of the Zanla forces that would be integrated with the Rhodesian and Zipra forces, I must confess, that was the most difficult time of my life. Having to share space with the former enemy proved a real challenge. I was stationed at Inkomo Barracks and hostilities simmered.

There were often open clashes especially between Zanla and Zipra on one side and the former Rhodesian soldiers on the other. The military instructors did not make it any easier as they also mocked us during training often creating more hostility.

For me, I could not picture myself ever sharing social space with those that sought to kill me during the war. What had changed that would make them forget their resolve? Yes, they had signed the agreement that led to the one man one vote, but had they done so freely? No! The escalating war and the subsequent losses they had suffered had forced them to surrender. What guarantee was there that they would not go back to their default mode? Until today, I tell you, my comrades and I feel we gave the enemy too much lee-way.

All the disturbances that were reported in camps were as a result of the suspicion that existed among former foes. All the parties remained suspicious of each other. It was only during the Mozambican campaign when the Zimbabwe National Army went to defend our Ferruka Pipeline that we began to reach out to each other and work as a team. For once, we worked as a team, with all suspicion gone. And indeed, we prevailed!

PK: Is today’s Zimbabwe what you envisaged as you fought for the liberation of this nation?

CC: To some extent yes. I fought for the liberation of this country. I fought for the removal of racism. I fought for free speech. I fought for equal opportunities for both black and white, men and women. I fought for blacks to reclaim their land that had been stolen by the colonialists. I just wanted a country where everybody was free to exercise their rights. I am saddened though, that we still have inequality where one race appears superior to the other. Yes, I fought for the land. And I am happy that a lot of blacks got land through the land redistribution effort. I am happy for those black families that got it. Like what my grandmother always reminded me that I still had not done my gawu portion. I still have some outstanding work to do. I will continue to defend this land.

I was retired from the army in 1998 and would have expected my now 35-year-old son, Clifford, to have been afforded a chance to serve there. But today, the nearer he has been to serve this nation is through his job as a security guard.

I am unhappy with the level of indiscipline and corruption amongst cadres. And I speak most for my comrades. Being the disciplined cadres that we are, we will continue to defend Zimbabwe notwithstanding the shenanigans of those that have taken advantage of the freedom we fought for.

I wish Government would do more for the war veterans. Is it not ironic that it is only in Zimbabwe where war veterans are looked down upon and mocked? All over the world war veterans are venerated and live comfortable lives. Even when you try and compare us with our neighbours in the region, we fare badly. We remain hopeful that our leaders in the Second Republic are mindful of us because some of us are destitute. I trust that our leaders will work towards the improvement of the living standard of ordinary citizens.

PK: What does independence mean to you?

CC: For me independence means the real work has begun. Those that we fought against are still alive and want to see the downfall of Zimbabwe. Remember, the colonialists have always believed they were superior to us. So, my plea to fellow Zimbabweans is not to fall into the trap of fulfilling their belief. When we let Zimbabwe down through corruption, they gleefully point fingers at our failure. For me independence means I have to go into serious defence of my country’s interests.

PK: Lastly, do you feel appreciated for your efforts in the liberation of this country?

CC: The New Dispensation has a huge task to realign what we fought for and our lived experiences. I have listened to some sentiments prodding us to take sterner action in defence of the revolution.

The discipline that I earlier on talked about forbids us to run riot in an effort to correct the situation. I remain hopeful that something will be done for me and my comrades. We did not go to war in exchange for payment but for the sake of future generations’ respect, all we ask for is a decent life.

Comments