Africa faces grave risks as global temperature could hit the 1.5 degrees threshold

Sifelani Tsiko Agric, Environment & Innovations Editor

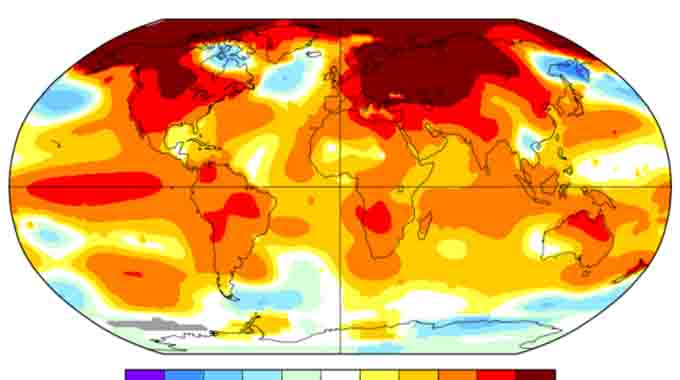

Intensifying climate hazards could put millions of lives at risk in Africa as there is a 50:50 chance of average global temperature reaching 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels in the next five years, according to a new report by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) published recently.

The Global Annual to Decadal Climate Update also reveals a 93 per cent likelihood of at least one year between 2022 to 2026 becoming the warmest on record, thus knocking 2016 from the top spot.

In the report released this week, the chance of the five-year average for this period being higher than the last five years, 2017-2021, is also 93 per cent.

The 1.5 °C target is the goal of the Paris Agreement, which calls for countries to take concerted climate action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to limit global warming.

“I agree totally with the findings of the report. Things are increasingly going bad for our climate,” said Prof Desmond Manatsa, a climate science expert at Bindura University of Science Education.

“Africa faces the highest combined physical risk from climate hazards like water stress, storms, wildfires and floods among other problems. Africa is extremely vulnerable to and bears the brunt of drought, flooding, cyclones and other climate change-led weather events.

“If global temperatures hit the 1,5 degrees threshold, things will be worse for Africa.”

Climate experts all agree that increasing temperatures and sea levels, changing precipitation patterns and more extreme weather are threatening human health and safety, food and water security and socio-economic development in Africa.

Dr Leonard Unganai, program coordinator and climate change expert with Oxfam in Zimbabwe, said Africa and the world should be concerned about the rising global temperatures which will hit the poor communities hardest.

The poor often face greater exposure to climate hazards, such as more extreme rainfall or drought conditions and have fewer resources to cope.

“Indeed, I have seen the WMO report and we all need to be concerned with the rate of global warming and the accompanying climatic changes,” Dr Unganai said.

The chance of temporarily exceeding the 1.5°C threshold has risen steadily since 2015, according to the WMO report.

Experts said, back then, it was close to zero, but the probability increased to 10 per cent over the past five years, and to nearly 50 per cent for the period from 2022-2026.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change further states that climate-related risks are higher for global warming of 1.5 °C than at present, but lower than at 2 °C.

Last year, the global average temperature was 1.1 °C above the pre-industrial baseline, according to the provisional WMO report on the State of the Global Climate. The final report for 2021 will be released on 18 May.

WMO said back-to-back La Niña events at the start and end of 2021 had a cooling effect on global temperatures. However, this is only temporary and does not reverse the long-term global warming trend.

Any development of an El Niño event would immediately fuel temperatures, the agency said, as happened in 2016, the warmest year on record.

By 2030, climate change could drive more than 100 million people globally into extreme poverty.

In Africa, 90 percent of the rural population depend on agriculture as their main source of income, and over 95 percent of arable farming relies on rainfall.

Rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall caused by climate change are expected to lower crop yields and raise prices.

The State of the Climate in Africa 2019 report, a multi-agency publication coordinated by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) also showed increasing climate change threats for human health, food and water security and socio-economic development in Africa.

According to the report, climate change was having a growing impact on the African continent, hitting the most vulnerable hardest and contributing to food insecurity, population displacement and stress on water resources.

SADC countries have recorded 36 percent of all weather-related disasters in Africa in the past four decades, according to UN reports.

These affected 177 million people, left 2,7 million homeless and inflicted damage in excess of US$14 billion.

Climate change continues to increase its frequency, intensity and duration with more destruction from cyclone-induced floods being felt in the region.

Tropical cyclones and severe thunderstorms have been the most destructive in Southern Africa, posing the greatest threat to infrastructure and displacing millions of people.

The weather-related disasters have led to huge economic losses in the region. In 2019, Cyclone Idai cost Zimbabwe US$274 million and Mozambique US$3 billion, 1.6 percent and 19.6 percent of their respective GDPs that year.

Comments