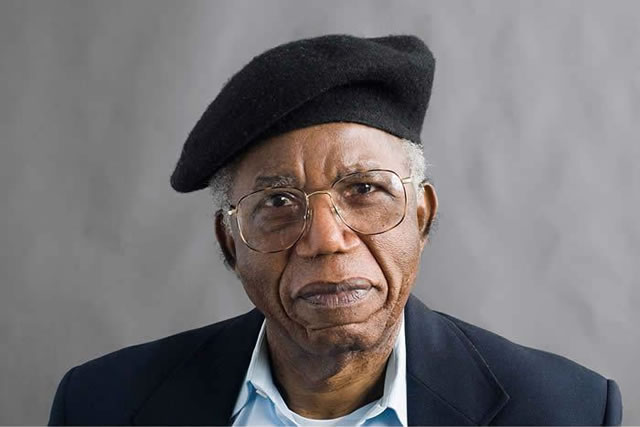

Achebe, African Renaissance

Stanley Mushava

Chinua Achebe commands the presidium of African literature. From varied domains, as an author, public intellectual and elder statesman, his work provoked a cultural revolt that became the framing point for later African voices.The Nigerian novelist’s death on March 21 this year occasioned a flare of indignation over his failure to land the Nobel Prize, won by his compatriot, Wole Soyinka, in 1986, despite the trailblazing outlook and universal renown of his work.

“My position is that the Nobel Prize is important. But it is a European prize. It’s not an African prize,” Achebe told Quality Weekly in 1988.

Two months after Achebe’s death, Soyinka told Sahara Reporters that he had received a series of letters asking him to put Achebe forward for the prize.

Soyinka slammed calls for the posthumous conferment of the prize, which is impossible in terms of Nobel Prize procedure, a disservice to Achebe as they negate his lifetime accomplishment to thwarted expectations.

“Chinua is entitled to better than being escorted to his grave with that monotonous, hypocritical aria of deprivation’s lament, orchestrated by those who, as we say in my part of the world, ‘dye their mourning weeds a deeper indigo than those of the bereaved,’” Soyinka said.

However, although Achebe was an Igbo cockerel, to borrow his own proverbial propensity, his crowing awakened the whole of Africa, hence the regional indignation. As Ben Jonson said Shakespeare was not of age, but all time, it can safely be said of Achebe, he was not of Biafra, but of Africa, if that too does not circumscribe the universal significance of his work.

Posthumous accolades for Africa’s foremost literary notable keep pouring in and from November 5-8 Africa celebrates its own with a conference tag-lined “Chinua Achebe: The Coming of Age of African Literature,” to be hosted by the Pan-African Writers Association in Accra, Ghana.

Some authorities suggest that Achebe was evaded by the Nobel Prize because his work was critical of racism in the West and because of his famous rebuttal of Joseph Conrad over his racist portray of Africa in “The Heart of Darkness.”

The grand patriarch of black writing and founding editor of the African Writers Series scaled up the dizzy arena when Africa was just a construct of offshore lenses in world literature. Mean stereotypes, then, ran the tapestry of Europhile narratives which reduced Africa to the backyard of civilisation.

Authors and intellectuals occasionally toured Africa from the comfort of their imaginations, conjuring up overstretched images to justify the Dark Continent mantra. Racism was staple-fare and the evolutionary theory placed Africans centuries behind the rest of the world, ostensibly because they were yet to ‘’evolve’’ to the level of man.

Conrad earned the chief apostleship of this creed with his novel “The Heart of Darkness.” Conrad’s novel became a seminal masterpiece acclaimed far and wide, despite scathing antipathy and revulsion against blacks.

The institutionalised insult on Africa landed on the raw nerve of a 36-year-old Achebe, then a lecturer in the University of Massachusetts’ English Department and prompted a counter-missive that became the framing point of African literature for generations to come.

“Although the work of redressing which needs to be done may appear too daunting, I believe it is not one day too soon to begin,” Achebe declared in his seminal paper, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’” published in the department’s literary journal three years later, in 1977.

“Conrad saw and condemned the evil of imperial exploitation, but was strangely unaware of the racism on which it sharpened its iron tooth.

“But the victims of racist slander who for centuries have had to live with the inhumanity it makes them heir to have always known better than any casual visitor even when he comes loaded with the gifts of a Conrad,” wrote Achebe.

Ngugi wa Thiongo was prompted by a similar realisation that colonialism was not a political edict, but a mental condition to pen “Decolonising the Mind” in 1986, 23 years after Kenya’s independence.

Achebe exempted Conrad from originating the image of a dark continent: “It was and is the dominant image of Africa in the Western imagination and Conrad merely brought the peculiar gifts of his own mind to bear on it. The stereotyping of Africa into a jungle of savages, Achebe argued, was premeditated to lift the burden of conscience from Western slave-drivers.

In turn, he resolved to use his own peculiar gifts to upstage Conrad and came up with the counter-masterpiece, “Things Fall Apart.” Later African intellectuals have rejected as racially motivated the theory of evolution which places blacks behind whites in terms of the rate of development.

Professor Felix Kotonuh-Ahulu articulates this backlash against evolution as neither rationally plausible nor ethically imperative in his review of Dr Carl Wieland’s One Human Race — The Bible, Science, Race and Culture for the August-September 2011 edition of the New African.

This band of African intellectuals borders on historical allusiveness and scientific demonstration to demonstrate how the downward variation of education, falsely called enlightenment, to suit Western interests at the expense of the subcontinent, unhinged the floodgate for moral bankruptcy.

Kotonuh-Ahulu draws a cross-section of the racially charged situation that obtained in the West as a result of the evolutionary conspiracy. In Australia Tasmian Aborigines were regarded as “wild beasts whom it is lawful to exterminate.” Aborigines were virtually wiped out by European settlers, with the last full-blooded Tasmian dying in the 1870s.

These examples serve to demonstrate how such a scientifically hollow theory as evolution has been used without the burden of ironclad evidence to legitimise the subjugation of one group of people over the other.

More African voices after Achebe must work up the proliferation of counter-scripts to debunk pseudo-scientific, discriminatory and self-serving character of Western education. The espousal of a colonial language for the articulation of native discourse, when there were hundreds of African languages confronted Achebe and his peers with issues of credibility.

To Anglophile writers of Pan-African sensibility, the matter was a prickly nettle on the conscience, but the obvious advantage of English was that it presented a universal medium. Achebe was the first black writer of international stature to level a legitimate compromise against the problem.

“Things Fall Apart” and later novels raised the bar from adoption to adaptation. The language was weaned from its latent codes of subjugation and imperial relics. Recourse to native tradition gave English an African accent.

Achebe’s inaugural offering became an experimental precedent for later artists. Soyinka later officiated the marriage of the Yoruba proverb and the English play to a photo-finish. In Zimbabwe, Charles Mungoshi’s “Stories from a Shona Childhood” and “One Day Long Ago” loaded English rifts with African ore, to domesticate John Keats’ famous line.

“I think that once you have mastered a language it’s your own. It can be used against you, but you can free yourself and use it as black writers do — you can claim it and use it,” South African writer Nadine Gordimer said in an Atlantic Unbound interview.

Achebe stayed the course with unsparing audits of post-colonial African society as “Anthills of the Savannah,” “A Man of the People” and “No Longer at Ease,” based on his conviction that the writer has a moral obligation to side with the powerless against the interests of power.

In the course of his accomplished career, he received more than 30 honorary degrees from universities across the world and several prizes stretching from 1982 to 2010. The upcoming conference in Accra is expected to introspect into African literature from its infant dispensation to the contemporary era where there is an apparent lack of direction after the exhaustion of themes bordering on colonial hindsight.

Leading writers and literary authorities, including Nobel laureates, from Africa and beyond are billed to participate at the conference. Young writers, language artists and literary devotees are also expected to attend.

Discussion points will include “Confronting racism and hegemony in world literature: Extending Achebe’s critique of Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” “Beyond and Within the Writer’s Imagination: Politics and Political Commitment” and “Achebe and the elusive Nobel Prize for Literature: Fathoming the Nobel in the works of African Nobel laureates in Literature.”

Beyond these rambling post-mortems, the conferences will also discuss “New Directions in African Literature,” African Literature and Pan-Africanism,” “Governance and Responsibility in African literature,” and the “The African Writer and the struggle for African Renaissance.”

Achebe and contemporaries belonged to the golden age of African literature and his death signalled the close of that age. African literature has, by and large, veered off-course, lapsing into trivialisation and myopic treatment of universal questions.

Budding writers angling to soar beyond where Achebe left may glean pertinent nuggets from William Faulkner’s Nobel acceptance speech.

“I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will someday stand here where I am standing,” Faulkner said.

“Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up?

“Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

“He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed — love and honour and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice,” he said.

My personal submission is that African literature has been dealt poetic justice by the alternative proliferation of evangelically-themed and motivational titles because of its lack of moral certainty.

Although literature flourished in the era of Achebe and his contemporaries it had a latent sell-by date because African writers notably Bitek, Liyong, Ngugi, Soyinka and Achebe himself subscribe to a world of dualities and deny the necessary stratification of right and wrong.

As a result, one encounters equivocation in Achebe’s works such as The Problem with Nigeria and There was a Country divisive overtones stamping out a broader nationalistic mandate and private decadence set against public heroism in A Man of the People and Anthills of the Savannah.

The Accra conference is a welcome first step towards the fresh introspection of African literature.

Comments