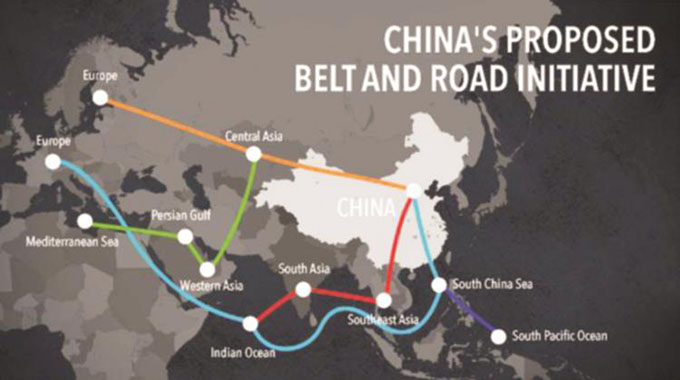

Belt and Road Initiative: What’s in it for Africa?

Ian Scoones Correspondent

The huge Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum recently concluded in Beijing. A total of 37 heads of state attended, along with droves of policy advisors and numerous thinktanks and research institutes, including IDS where I work.

Monica Mutsvangwa, Minister of Information, Publicity and Broadcasting Services, attended on behalf of the Zimbabwe Government. By all accounts it was a lavish affair, with grand speeches and big commitments totalling $64 billion. But what to make of it all from an African perspective?

As discussed on this blog several times before, while Chinese engagements with Africa can be framed in terms of “new imperialism” or part of a benign process of “mutual learning”, in practice a more nuanced perspective is needed. African states have agency in the process of negotiation, and the Chinese always adopt an incremental and adaptive approach to policy, in Africa as in China. There is no single top-down plan to be forced on unwilling recipients.

As our studies of Chinese (and Brazilian) investments in African agriculture (in Ethiopia, Ghana, Mozambique and Zimbabwe — reported in an open access World Development issue) showed, what emerges varies from country to country, project to project, depending on how negotiations play out. And this very much depends on which Chinese state-owned company, from which province in China, is involved, and how African states and officials negotiate. Sometimes the outcomes are disastrous — inappropriate technologies and failed projects — but sometimes positive dynamics unfold. No surprises here: Chinese engagements are very similar to aid from Denmark, the UK or the US, just more focused on productive infrastructure and perhaps more honest and straightforward.

Chinese President Xi Jinping

Beyond the BRI rhetoric

At the BRI Forum there was grand talk of mutual benefit, inclusive approaches and green and sustainable development. Just as with Western aid, forget the rhetoric, and look at the practice. Chinese geopolitical and commercial ambitions are clear. The BRI is certainly about regional, even global, political influence, especially through trade. With coal mines and power stations being opened under its banner, forget the green credentials for now. As a strategic player, who plays the (often very) long game, the benefits to China of all the roads, ports and other infrastructure being built are obvious.

This does not mean though that such investments are disadvantageous to host countries and regions, just because China benefits too. The TAZARA railway built between Tanzania and Zambia in the early 1970s still provides an important trade link, assisting economic integration. New investments may too — but only if designed in the right way, and subject to careful deliberation and negotiation at a local level. Being too eager (or desperate) to receive Chinese investment could be dangerous.

Whenever, African countries pitch their needs for financial support they must not do it in a way that is more of an invitation to a resource grab but as a way that promotes open bilateral negotiations around mutually beneficial investments.

Corridors for development?

So what might a corridor development look like that has wider benefits for development, and is not simply a route to facilitating extractivism? A recent study carried out along the eastern seaboard of Africa — in Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique — has looked at four very different corridors, all notionally connected to the BRI — LAPSSET, SAGCOT, Nacala and Beira. All involve major port and road/rail developments, linked to a variety of energy and agricultural investments of varying scales.

Our research contrasted corridors constructed as “tunnels”, conducting valuable resources out of a country and importing goods to metropolitan centres, and “networks”, that allow linkages to rural hinterlands and a dynamic of development associated with the investments. Each of our case studies showed elements of both at play.

Corridors, as Euclides Gonsalves explains for Mozambique, are about “acts of demonstration’” linking political ambitions to local development. The grand, stylised performances at the BRI Forum in Beijing also play out in villages and project sites in African rural areas. Enlisting and enrolling actors, and material artefacts (grain silos, extension centres, new roads and so on), are part of the game. Enacting corridors has political and material effects, as some people are included and some excluded, and certain political interests are promoted. The net benefits may be positive, but the performative aspect is key, he argues.

Many corridors are about constructing imaginaries, and creating an economy of expectations, Ngala Chome argues for LAPSSET in Kenya. The corridor has been long planned, and while port facilities are being built in Lamu, many follow-on investments have not yet materialised. Anticipation, expectation and speculation create a new political economy around prospective corridor sites, as we see in the pastoral rangelands of Isiolo where the pipeline and road is expected to traverse. As our work under the PASTRES project shows, pastoralists in these areas complain this has resulted in a massive growth in speculative land deals.

A struggle over development and its directions is unleashed by corridor developments. Everyone has been crying out for investment, but when it comes, the terms of incorporation are inevitably uneven. As Emmanuel Sulle shows for the sugar and rice plantations in the SAGCOT corridor area of Tanzania, processes of displacement and disenfranchisement unfold. And this is even with “inclusive” business models, such as outgrower schemes, heavily promoted by agricultural investors across the corridors.

Networks not tunnels

What are the policy recommendations from our APRA corridors research? Here are the highlights:

Policy appraisal must include political economy analysis to explore the potential winners and losers. External capital/infrastructure investment mobilises local interests, including local capital and the state, creating new patterns of differentiation. This means appraisal must go beyond the standard economic assessment to a wider social and political analysis.

The design of a corridor — and the associated business models promoting agricultural investment — make a big difference. Opportunities for a more networked organisation, avoiding the limitations of a “tunnel” design, need to be explored, especially around the design of transport infrastructure that can benefit local economies.

Terms of inclusion and exclusion in corridors are mediated through a range of local institutional and political processes. For example, land speculation and the revitalisation of older conflicts over resources may occur as a result of corridor development. Benefits may be unevenly shared in already unequal societies, with women and poorer households missing out.

Processes for negotiating corridor outcomes require the mobilisation of less empowered actors — including women and poorer people — and their organisation around clear guidelines — such as those within the FAO Voluntary Guidelines on land tenure — that ensure terms of incorporation into corridor investments are not disadvantageous.

Support for legal literacy and advocacy, as well as the organisation of disadvantaged groups, will help people to be able to articulate demands. This requires building on local organisations and networks to help counter the power of appropriation of local elites in alliance with the state and investment capital.

All these are relevant for any investor, and for any corridor-style investment. I hope African governments and the BRI planners take note, and avoid the rush to invest and take a more patient, deliberate approach that creates networks not tunnels. — Zimbabweland

Comments