Zim’s powerful music of the struggle

Anakwa Dwamena Correspondent

In April of 1980, when Bob Marley arrived to headline the Independence celebrations that would see Rhodesia become Zimbabwe, his song “Zimbabwe”, the centrepiece of the “Survival” album, was the most popular foreign song in the country.

Marley, whose religion of Rastafarianism had long preached cultural and political resistance against white oppression in Africa, wanted to “build a blood-claat studio inna Africa, have hit after blood-claat hit”—so much so that he spent thousands of dollars flying lighting and sound equipment to Zimbabwe to create a concert atmosphere that would match that of Madison Square Garden.

In Zimbabwe, popular songs were central to the century-long fight to end the colonial system, and Marley’s claim that music was “the biggest gun because the oppressed cannot afford weapons” was nowhere more resonant.

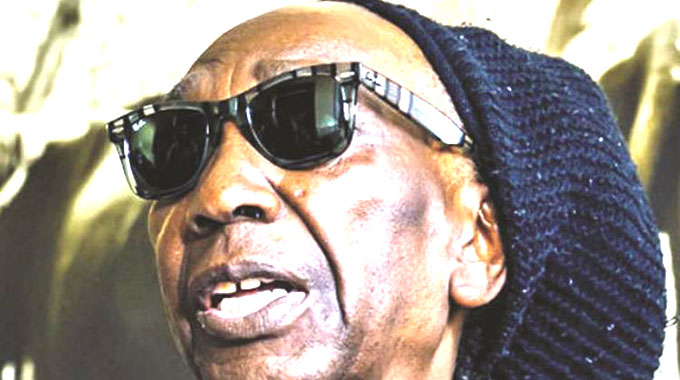

After Marley’s performance that night, when he shed tears watching the Rhodesian flag come down and Zimbabwe’s go up, the local musician Thomas Mapfumo took the stage.

Mapfumo was a leading singer of Chimurenga music, the music of struggle. I spoke with Professor Mickias Musiyiwa, of the University of Zimbabwe, who told me that Chimurenga music continues to be “one platform that Zimbabweans always resort to whenever they want to express their grievances against their leaders and against Western imperialism”.

The word comes from the name of Murenga, an early ancestor and warrior of the Shona people. In Zimbabwe’s liberation war, of the 1960s and 70s, the military wings of guerrillas based in Mozambique and Zambia set up choirs to sing Chimurenga songs that derived from folk hymns and other folk songs.

These hymns connected the living with the world of the ancestors and recorded the struggle for those to come. Revolutionaries played these songs at rallies held in urban areas and at all-night vigils called pungwes, where guerrillas and peasants would come together to sing.

Songs like “Muka, Muka!” (“Wake Up, Wake Up!”) and “Tumira Vana Kuhondo” (“Mothers Send Your Children to War”) were sung to politicise and educate Zimbabweans about why the war for Independence was being fought.

“The song became the classroom, so to speak, just like in South Africa and in Kenya, through which people could access information of what was happening in different parts of the country,” Maurice Vambe, a professor of African Literature at the University of South Africa, explained to me.

The songs could also correct a historical narrative. Songs such as “Vakawuya Zimbabwe” (“They Came to Zimbabwe”) narrated the exploitation of Zimbabwe and sought to revive old stories about pre-colonial times. Much like reggae would seek to do, the music was making contemporary social commentary and preserving ancient cultural memory.

Although Mapfumo was not among the guerrillas in Mozambique and Zambia, his music championed the war for Independence, leading to his detention and multiple arrests. His popularity as the leading Chimurenga musician was fuelled by his band’s adaption of the mbira, a thumb piano that is central to Shona spiritual com- munication.

By using a traditional instrument — particularly one with ties to ancestor worship —Mapfumo was signalling his participation in a cultural revolution against colonial rule.

In the first half-decade after Zimbabwe won its independence, Mapfumo, like other Chimurenga musicians, would sing songs like “Mabasa” (“Let’s Get Back to Work”), about the need for unity in order to build the new nation.

Mapfumo, who is now 72, returned to his country last year after 10 years of self-imposed exile, in Oregon, as a persona non grata of the Mugabe regime. —Abridged from The New Yorker.

Comments