Zimbabwe and the beauty of Spring

Dr Sekai Nzenza on Wednesday

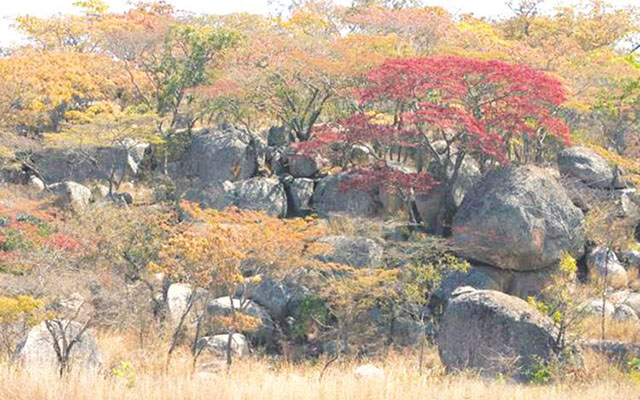

Every year, when September comes to Zimbabwe, the trees welcome new leaves. You see the buds at the end of the mutondo branches. Then slowly, the buds open. Fresh, soft orange leaves emerge. Within two or three days, the small leaves change colour to a beautiful yellow, pink and orange. Each mutondo tree celebrates the new leaves at different times within September and early October.

When I see the colours of the pfumbvudza, I long for the freedom that it brought when we were young, growing up in the village. This was the season of playing and swimming. There was no hard work to be done in the fields. We were free to roam the mountains, the forests and the hills, looking for wild fruits.

At night, while the adults talked to the ancestors during dry season ceremonies, we children played games like chinungu, gwendere gwendere, jejejeje jerekuje, chidhange chidhange, dzwitswi, vasikana iwe, pfukumbwe, zvirahwe, tsoro, mapere, pada, nhodo and many others whose English names we never had. The forest was an open orchard for us to pick indigenous fruit of the dry season. And there was plenty of it. We picked nhunguru, matohwe, matamba and hacha.

Not too far from the matamba tree near the homestead were several muhacha trees full of the round fruits with hard seed that tasted like nuts inside. You did not climb muhacha because its trunk was thick, with a hard rough bark. We competed with donkeys for the hacha fruit because they too loved it. Hacha, when pounded, produced juice and made tasty beer.

We also had a big muzhanje tree in my grandfather Sekuru Dhikisoni’s field. By the time pfumvudza came, its branches were heavy with the green fruit which would only get ripe in November and December when the rains came. We wanted mazhanje to ripen quickly so we dug a hole in the ground and stored several unripe mazhanje in the ground to make a pfimbi, or treasure spot.

Then we placed a sign so we could remember where the pfimbi was. We used a special thorn twig, a stone or pieces of dry grass. On the fourth or fifth day we came to dig the pfimbi and take out the ripe juicy mazhanje fruits.

It was during the spring time of the pfumvudza that we played childhood games. We picked the leaves and played games at being husbands and wives, Baba naAmai, cooking for children and pretending to do what parents do in the home. We chose the children among ourselves. That way we imitated how our parents and grandparents related to each other. We learnt how to discipline children and what to add to the meals. The game was called matakanana.

In order to prepare the meal, we picked the tender fresh leaves, and pounded them with a stone against another stone, making mashed leaves. This was our relish. Then we picked the empty cups of a mutamba tree to use as clay pots for making sadza. We added water to the mashed leaves and stirred. Then we added soil to water, pretending to cook sadza. When the food was ready, we sat down as a family and had a “meal”.

Afterwards, husband and wife went to bed on a sleeping mat while the children were secluded in another room. Nothing happened between husband and wife. These were just games, enabled by the new lazy season of the pfumbvudza. It was part of our socialisation process.

My grandmother, Mbuya VaMandirowesa, told us that the spring time of the pfumbvudza also meant that evil businessmen who preyed upon young people were preparing their sharp knives so they could kidnap one of us on the way from school. The evil men were called mabhinya. She said we should not walk home alone from school because our nearest businessman we called Chibage was hiding under the pfumbvudza trees. She said Chibage would kidnap one of us, kill him or her and then use the body parts for muti or medicine that would miraculously make him very rich. This was called kuchekeresa.

It was rumoured that Chibage had already killed one or two people before he opened a small shop near our village. This shop was called the “hotdog”. Even though he did not make hot dogs. At that time we did not know what hotdogs were. Still, the shop was called Chibage’s Hotdog. Chibage was a tall light-skinned man with a big stomach. When the spring time came, we waited for our older brothers to finish school so they could protect us against Chibage, the evil businessman.

Chibage’s hotdog did not expand beyond what it was. When the liberation war for independence started, Chibage closed his shop. People said he had failed to find a young person to kill during the spring time of the pfumbvudza. Now it was too late to wait for another spring because there were liberation fighters hiding in the bush waiting for the Rhodesian soldiers. The war was spreading right across the country. Zimbabwe was going to get its independence from colonial rule. As we grew older, we met boys and girls of similar age along the paths from church or from Muzorori & Sons Stores.

Mbuya VaMandirowesa told us to stay away from the boys at the time of the pfumbvudza because it was the new season of love and rebirth. The smell of love came with the new leaves. We should always run away from the boys waiting behind the pfumbvudza trees, looking for love. This was not love, Mbuya said, it was lust brought on by spring and lack of something to do. The game of matakanana was over, she said. We listened to Mbuya because we knew the dangers of playing with boys under the mutondo trees that were covered by pfumvudza.

Last week I drove towards Mazowe going north. The brilliant colours of the trees spoke of the annual spring time in Zimbabwe. I spotted couples walking along the road or sitting under a tree as the big red sun was setting. The haze covered the sun’s setting rays and there were many soft colours of red, orange and a slight tint of purple.

In less than an hour, the sun went down and I imagined the young lovers possibly embracing, maybe kissing or going further to do what Mbuya VaMandirowesa said should not be done by young unmarried people.

But Mbuya did not know that young people would continue to do what they are not supposed to do, especially in spring, when the weather is warm and the trees are beautiful with new colours. As the hills celebrate new leaves, we wait for the rain called Bumharutsva.

This is the rain that comes soon after the cold spell. Sometimes they call it Gukurahundi, the rain that takes away dry rusks and empty shells of millet and sorghum after the harvest. The cold spell has since gone but we have not seen the rain as yet. Maybe a short period of the cold wind is still on its way. But it may not come. Seasons seem to be changing. We had plenty of rain this year and some trees have not shed their leaves to give us pfumvudza as yet. But they will soon do so. There is no new life without shedding off the old.

Across the Zimbabwean countryside, the hills are full of colours. In Europe, they would call them the colours of the autumn. But not here. Our spring time is autumn in Europe and also in parts of America. Pfumbvudza continues to give us the colours of life, the memories of peace and the innocence of childhood games.

We are in the new season of heat. In the morning, we feel the cool breeze and we see the sun rising. It’s a big red ball. The trees give us fresh green and yellow leaves. They speak of rebirth and freshness. Soon the cicadas will come, singing louder and asking the rain to come early. Ah, Zimbabwe, despite everything else, you never lose the beauty of spring.

Dr Sekai Nzenza is an independent writer and cultural critic

Comments