Zim: From pariah to partner — series finale

Tichaona Zindoga Political Editor

Pariah” is an English word derived from a South Indian term “paaiyr” which refers to a group of lower “caste” outcasts or untouchables.

In the field of international politics and relations, the term refers to ostracised countries that are excluded from the community of nations as punishment for their behaviour.

A closely related term is “rogue”. Robert S Litwak and Robert Litwak (2000) explain that the status of pariah or rogue “derives from a regime’s domestic behaviour (i.e., how it treats its own people) or from external actions that violate important norms (such as territorial aggression or use of terrorism)”

Paul D Hoyt (2000) writing in “The Journal of Conflict Studies” is even clearer.

He suggests that in the world today – the post-Cold War era – the United States of America arbitrarily ascribes these terms to countries that it does not agree with.

Explains Hoyt: “In the rhetoric of American policymakers, the greatest threat to peace and stability since the end of the Cold War is the existence of ‘rogue’ states; states which are accused of violating international norms of behaviour by, for example, sponsoring international terrorism, committing human rights abuses and seeking weapons of mass destruction.

“Also referred to as ‘pariahs’, ‘outcasts’ and ‘outlaws’, these countries are commonly the subject of diplomatic isolation, economic embargo, political and economic sanctions, and even military attack.

“Playing such a central role in the thinking and policies of American decision makers, it becomes important to evaluate the place of such states as Cuba, Libya, Iraq, Syria, Iran, the Sudan and North Korea in the current international environment.”

Hoyt discusses the issue further and makes a critical intervention.

Condoleeza Rice

He says: “. . . it is worth noting that there exists a debate as to whether the term ‘rogue state’ refers to an objective category of nations or, instead, is a subjective label attached to states based on the perceptions and political interests, of others.”

Outposts of tyranny and axis of evil

Closely related to the concepts of pariah and rogue states, one could add two terms that American politicians have used in recent times.

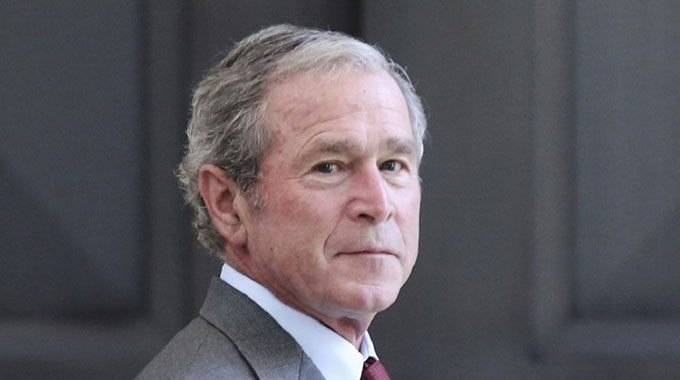

In 2002, US President George W Bush, during his State of the Union address, made an (in)famous speech in which he referred to an “axis of evil” to describe foreign governments that, during his administration, allegedly sponsored terrorism and sought weapons of mass destruction.

He singled out North Korea and Iran.

Three years later, in January again, his Secretary of State nominee, Condoleeza Rice, brought a fresh term in keeping with the nomenclature of US’ opponents.

“The time for diplomacy is now,” BBC quotes her as beginning.

“Our interaction with the rest of the world must be a conversation, not a monologue.”

She said that in the first years of the 21st century, (American idea of) liberty could be spread around the globe.

“To be sure, in our world, there remain outposts of tyranny, and America stands with oppressed people on every continent, in Cuba, and Burma, and North Korea, and Iran, and Belarus, and Zimbabwe,” she said.

Zimbabwe, the pariah and outpost of tyranny

This is the final part of a five-part series that we have carried under the title, “Zimbabwe – In search of the old normal” wherein we sought to look at how Zimbabwe can make a transition from a multi-layered crisis that it has been reeling under in the past two decades or so as a function of a complex mixture of internal and external factors.

It was a proposition that Zimbabwe could make good of the transition by simply adopting some core fundamentals in governance, economy, social, and administration.

This can be achieved by simply adopting some fundamental aspects of the previous era before the crisis.

We likened Zimbabwe to a post-conflict country needing reconstruction.

In this final instalment, we look at how Zimbabwe can be reintegrated into the “family of nations”.

The concept of family of nations is widely used in the rhetoric of international relations and political science.

It is the antithesis of terms such as pariah, rogue and axis of evil alluded to above.

When Condoleeza Rice named Zimbabwe as an “outpost of tyranny”, the ramifications were great.

It was the height of Zimbabwe’s punishment, exclusion and ostracisation by the West, led by the US.

On December 21 2001, Bush had signed into law the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act, which pronounced a policy of sanctions which the US would enforce in partnership with its partners in the West.

In 2003, he signed an executive order declaring a state of emergency with respect to Zimbabwe, claiming that the country posed an extraordinary and continuing threat to the foreign policy of the United States.

In the same period, the 27-member European Union bloc imposed similar sanctions on the Southern African nation.

The US and the EU accused Zimbabwe of “gross” human rights violations as well as failure to respect the will of the people by failing to hold what they would deem free and fair elections.

A key background to these actions is that former coloniser of Zimbabwe, Britain, had exported its bilateral dispute with the African country over land, which the former took away from a handful of white farmers and distributed to two million black families.

The sanctions were meant to cause a change of behaviour on the part of Zimbabwe, led by then President Robert Mugabe, by way of an economic squeeze and a fomenting of a humanitarian situation which could force him out.

From pariah to partner?

The sanctions on Zimbabwe have progressively been relaxed, but remain in place.

However, there is a glimmer of hope that these can be removed: Mugabe, the West’s tough customer, is no longer in power.

He left the stage in November 2017, unharmed by the Western sanctions, which, in fact, would on occasion give him political ammunition in a classic ju-jitsu. Zimbabwe is in a transition.

The country will go for crucial, age-defining elections on July 30.

The elections are likely to be free and fair and credible, judging from the obtaining pre-election environment.

At the same time, there appears to be a lot of goodwill from the so-called international community.

Britain, which to all intents and purposes, triggered off the standoff between Zimbabwe and the West, has been the first off the blocks to embrace Zimbabwe in the post-Mugabe period.

It has even been seen to be bending over backwards to accommodate Zimbabwe, something attributable to its own problems with Brexit, its desire to catch up on the geopolitical dynamic and, of course, that it is the Queen’s wish to see Zimbabwe back in the Commonwealth – Britain’s symbolic expression of influence and glory.

The overtures are good for Zimbabwe.

With the forthcoming elections and successful transition, Zimbabwe is likely to shake off the unhelpful negative status of pariah into a global partner. Even a junior one.

Our American problem

But we have a problem. The United States of America may have gladly imported Britain’s dispute with Zimbabwe, but it is unlikely that it will withdraw with much grace.

It may actually complicate Zimbabwe’s reintegration into the family of nations.

This is because not only is the US capable of showing Britain the middle finger in pursuit of its own foreign policy goals – and it is doing that all over these days.

The thing is, the US has Zidera and the executive orders that Britain or any other country has no power to remove.

The same applies to the EU, which can invoke measures that a Brexited UK may not be able to stop.

It can be a checkmate, and we would need to pray hard it doesn’t get to that.

However, there are interesting signals that there could be a significant divergence of policy between Britain and the EU and US on the other side.

For the US, there are larger geopolitical issues at play.

Apart from wanting its pound of flesh (by way of diamonds, infrastructure and energy concessions), it may also be keeping a wary eye on China, which has a foothold on Zimbabwe.

However, Zimbabwe is in a better position diplomatically now than any other time in the last two or three decades.

Comments