Zim economy today, in 2020 and beyond

Persistence Gwanyanya, Correspondent

With hindsight, we now seem to agree that most of us, policymakers included, underestimated the depth of Zimbabwe’s economic challenges last year.

The performance of the economy last year seems to suggest that we lacked a deeper understanding of the true nature of the challenges, and, therefore, the potency of the reforms, which were introduced in October 2018.

Our economic problems are long-term and structural in nature. They formed over a long period of time, spanning over two decades and cannot be fixed overnight or over a short period of time.

Importantly, they are beyond economics and finance. Therefore, they can’t be fully tackled by economics and finance solutions only.

Barring the effects of economic shocks from the devastating drought and Cyclone Idai, it appears policymakers were overambitious in their 2019 projections, which were understandably based on their view of the efficacy of fiscal and currency reforms.

They also failed to anticipate the impact of monetary reforms, namely liberalisation of the exchange rate, which, arguably, had become long overdue.

The exchange rate was unrealistically maintained at par to the US dollar for a long time through unsustainable subsidies, including currency subsidies, arguably, as a soft lending strategy of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ).

Importantly, it appears policymakers failed to grasp the effects of administrative challenges in Government and State-owned institutions, which is a huge drawback on policy implementation, coordination and effectiveness.

Some managers in Government and at corporate level do not understand the current reform thrust as well as priorities of the day, which has seen them make economically unviable and costly decisions to the detriment of the whole economy.

Worryingly, some of them live in the past. They resist change, block or sabotage progress, are corrupt or have vested interests.

Equally worrying is the current political impasse, which stifled economic reforms. The impasse has also compounded the confidence crisis typified by deep distrust in Government policies and lack of cooperation in some quarters.

More still needs to be done to tackle corruption. There is a perception that what has been done is inadequate because graft is now everywhere and at all levels of the society.

Like what happened to China when it initiated reforms in 1978, a more radical and big bang approach is needed. Anything short of that may not inspire confidence.

Despite all these structural issues, our policymakers managed to convince international financial institutions (IFI), namely the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), who have normally taken a pessimist view on Zimbabwe, about the efficacy of the reforms in place to get the economy back on a recovery path.

These institutions largely agreed and endorsed both the Transitional Stabilisation Programme (TSP), and fiscal as well as monetary policy projections, which, like the Government, they have now significantly revised down.

This may also confirm my earlier assertion about policymakers’ failure to fully grasp forces at play, and, of course the damaging effects of unforeseen eventualities, notably drought and Cyclone ldai.

The Government revised down its growth projection from 3,1 percent to a contraction of 6,5 percent in 2019. Interestingly, again the revised projection is still within the range of the IMF and WB revised projection. WB projected the economy to contract by 7,2 percent last year.

The revised overall growth reflects underperformance in all sectors of the economy, key among them being agriculture, mining, tourism, manufacturing, electricity and water.

As a result of drought, agriculture, is now expected to contract by 16,3 percent, while the mining, tourism and manufacturing sectors are expected to contract by 12,3 percent and 4.3 percent, respectively.

Compounding this contraction is the under-performance of the electricity and water sector, which is expected to decline by 19.8 percent.

Following currency reforms, it was unsurprising that Treasury rolled out a supplementary budget of ZWL10,5 billion, which is actually larger than the initial budget of ZWL8,2 billion.

The effects of monetisation of past deficits required some measure of monetary accommodation, which partly explains the growth in money supply, which peaked at more than 80 percent around October 2019.

This drove prices up and accelerated currency depreciation. As a result, real values of salaries were eroded, leading to the impasse between the Government and its employees, notably doctors, who have been on strike for the last three months or so.

Going into 2020, we expect the effects of monetary expansion and inflation to drive prices up, especially in the first quarter of the year.

Normally, the impact of money supply growth is realised six to nine months down the line, meaning peak money supply growth of 2019 will result in price increases from April 2020 onwards.

Actually we have started to witness proposals for sharp increases in school fees estimated at around three to 10 times for next year by both schools and universities across the country. Government will definitely bow down to the pressure for wage demands as the cost of living escalates.

This, compounded with pressure to subsidise necessities, as a way to mitigate the impact of drought, as well as pressure to sort out the situation with utilities — water and electricity — and honour commitments on blocked funds at the exchange rate parity (1:1), will result in monetary expansion in 2020.

At one point, RBZ advised that it acknowledged a total of US$1.2billion as blocked funds, which need to be honoured. While indications on the ground are that these blocked funds are likely to be structured into long term instruments, there are other pressing creditors that will put pressure to be paid.

These factors, taken together, would suggest that another supplementary Budget is unavoidable. By June we may have another Supplementary Budget which, is likely to be higher than the current budget of ZWL63,6billion, probably large enough to take total budget to the total bids of ZWL136billion.

This only means 2020 growth is going to be significantly lower than 3 percent projected by Treasury. The worst case scenario is an economic contraction of 5,7 percent, while the base case (most likely scenario) is a lower contraction of 2,5 percent and best case scenario is a smaller growth of 1,7 percent.

The worst case scenario assumes another severe drought and unresolved political logjam in the country, while the best case scenario assumes a good rainfall season and some measure of political solution to the current political differences.

We expect inflation to peak at 700 percent in the first half of the year and go down to around 400 percent by year end.

The need to import mainly maize and basic foodstuffs may cause a measure of currency volatilities in the first quarter.

Treasury has so far committed to avail 40 000 tonnes of maize, for production of 32 000 tonnes of subsidised roller meal per month at a time when GMB stocks are running down.

The subsidy, together with those promised for the other six basic commodities, will help stabilise inflation if well-managed, but also has potential to destabilise the situation in the country, making it difficult to manage inflation.

However, more will depend on the effective implementation of monetary policy to reduce money supply growth and manage concentration of liquidity.

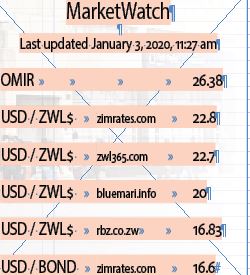

The current stability in the exchange rate is attributable to freezing of a couple of accounts suspected to be driving up parallel market rates. The revelation by RBZ that about half of total market liquidity is concentrated in the hands of a few large corporates is worrying as it may suggest the existence of a few drivers of exchange rates, making the forex market susceptible to manipulation.

The best case scenario assumes great strides in dealing with the leakage of funds from the fiscus through nefarious activities such as corruption.

Importantly, it assumes radical transformation of work culture and resolving of the high entropy levels (disengagement), weighing down the success of our policies.

It also assumes tangible efforts to deal with all housekeeping issues such as the machete wielding terrorists who are becoming a serious threat to the country’s peace and stability.

So as we transition, we should know that the journey is not as rosy as most of us think. This is only typical of reforms and transitions.

As such, we cannot afford to look back, but forge ahead building on the progress we made so far.

As we dig ourselves out, we should resist the temptation to repeat the mistakes that got us here.

Persistence Gwanyanya is an Economist, Chartered Banker, Trade Finance Specialist and founder of the Bullion Group. For feedback e-mail [email protected] or WhatsApp +263 773 030 691.

Comments