Whistleblower legislation can help curb corruption

Beaven Dhliwayo Features Writer

Corruption is a cankerworm that has eaten deep into the fabric of every system in Zimbabwe and it is a crime with such a despicable viral effect and disastrous tendency like a terror bomb.

Though it is more of an executive crime, no well-meaning government handles corruption with levity because the extremity of its ugly tentacles is capable of obstructing good governance.

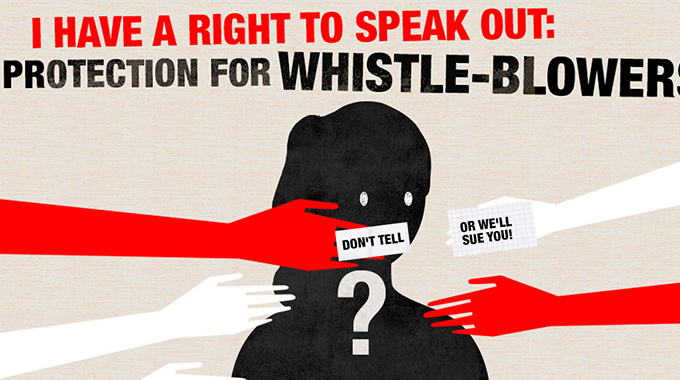

One of the major challenges in the fight against corruption is detecting and exposing the scourge.

Whistleblowing, therefore, becomes a veritable means to fight this cancerous crime.

Corruption, fraud, bullying, health and safety violations, cover-ups and discrimination are common activities highlighted by whistleblowers.

Recently The Herald ran an article titled, “President rescues ZESA whistleblowers”.

The article was in reference to the well-intended intervention by President Mnangagwa on the fate of eight ZESA workers who had disclosed some corrupt activities within the power utility.

The sin that was committed by the eight ZESA workers was exposing corruption at the parastatal, which saw the awarding of procurement contracts without following procedure.

The sanction of the sin was the dismissal of the workers who had made this disclosure.

According to reports, the affected workers have been on suspension for 15 months without pay.

The act of disclosing or exposing corruption by the ZESA workers is what is defined as whistleblowing.

Whistleblowing is the act of drawing public attention, or the attention of an authority figure, to perceived wrongdoing, misconduct, unethical activity within public, private or third-sector organisations.

Speaking at the recent Public Finance Management indaba, organised by the Zimbabwe Coalition on Debt and Development (Zimcodd), Norton MP Temba Mliswa (Independent) said one tool that has gained attention in recent years is the expanded use of whistleblowing in terms of incentives to encourage it and laws to protect whistleblowers.

“While whistleblowing alone is not a solution to corruption, it is one of the tools that can improve governance and create ethically and legally healthy organisations and governments.

“Because of the increasing recognition that whistleblowing is one part of an overall set of tools to expose corruption, many countries and international organisations are adopting legislation that legalises or encourages such behaviour.

“Zimbabwe should just follow suit. As Parliament, we must enact whistleblowers legislation which safeguards against reprisals from employers or powerful politicians,” he said.

According to Mliswa, the legislation must allow disclosure of information either internally to the legal entity concerned (Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission) or directly to competent national authorities.

The law should also establish “safe channels” for reporting the information, both within an organisation and to public authorities, while protecting whistleblowers against dismissal, demotion and other forms of punishment or reprisals.

Mliswa pointed out that there is also need to protect those assisting whistleblowers, such as facilitators, colleagues and relatives.

Among other recommendations, the Norton legislator said the law should mandate all companies to have a whistleblower policy in place that dictates how to manage and prevent reprisals and abuse of the facility and spells out rewards for useful information.

With the alarming rate of corruption in Zimbabwe whistleblowing can be one of the most effective ways of exposing malfeasance in the country.

Corruption continues to harm Zimbabwe, deterring growth, democracy and the fight against poverty.

The country ranks lowly on corruption indices.

Countries in Africa average 32 out of 100 in their Corruption Perception Index scores, and Zimbabwe is one of them.

According to the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, around 40 percent of all detected occupational fraud cases are identified by whistleblowers.

Historically, whistleblowers, the world over, have been denied the protection required to allow them to report wrongdoing, often leaving them exposed to retaliation.

According to the Ethics & Compliance Initiative (ECI), retaliation against US workers who report suspected unlawful activity within their companies is occurring “in ever-greater numbers”.

The ECI suggests that the rate of retaliation doubled between 2013 and 2018.

Thankfully, many jurisdictions have begun to offer greater legislative protection to whistleblowers in recent years.

“In 1998, two countries had whistleblower protection laws in place — the UK and US,” said Mark Worth, executive director of the European Centre for Whistleblower Rights.

“Today, at least 46 countries do, including about 20 in Europe, and about 10 each in Africa and Asia-Pacific. On paper, we have come a very long way in these 20 years.”

Standards developed by the United Nations (UN), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and non-governmental organisations, such as Transparency International and Blueprint for Free Speech, have greatly assisted with the development and passage of new laws with up-to-date provisions.

Anonymity is a core pillar. Whistleblowers should be allowed to report anonymously and their identity should not be revealed when a whistleblower reward is made.

This will encourage more whistleblowers to come forward if they know that they are protected by the law.

On the whole, whistleblower rewards, in general and in the corruption context specifically, remain a promising tool to detect and deter crime.

Careful design and implementation are necessary, because as for any powerful tool, these programmes can be well used to do great things, but also misused to do great damage.

Globally, however, it is clear that more must be done to shield whistleblowers from reprisals, as such, efforts are under way, across various jurisdictions, to improve whistleblower protection, both legislatively and within organisations.

Lessons can be drawn from South Africa where whistleblowers are instrumental in the fight against corruption.

South Africa is currently seized with an inquiry (the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into the Allegations of State Capture — Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector, including Organs of State) on the extent of corruption that might have taken place in the last 10 years.

So far, whistleblowers have revealed damning evidence on the magnitude of state capture and corruption within the South African government and state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

However, the concern is what happens to the whistleblowers after they release such information?

In Zimbabwe, it is not clear which laws or provisions in specific laws that protect whistleblowers.

This aspect of the law remains blurred and makes it extremely difficult for whistleblowers to enforce such legal provisions if at all they exist.

Moreover, no legal provisions have been adequately tested in the Zimbabwean courts to ascertain the veracity of such protection.

This level of uncertainty has contributed to the escalation of corruption in Zimbabwe.

The envisaged legislation should be comprehensive and must not let the whistleblower feel more vulnerable than protected.

If companies wish to encourage people to come forward, with regulators, they must continue to work to communicate the benefits of good systems and controls.

Whistleblowers are less likely to report workplace misconduct when their employers do not provide clear internal reporting channels.

In some settings, whistleblowing carries connotations of betrayal rather than being seen as a benefit to the public.

Ultimately, societies, institutions and citizens lose out when there is no one willing to cry foul in the face of corruption.

Public education is also essential to de-stigmatise whistleblowing, so that citizens understand how disclosing wrongdoing benefits the public good.

When witnesses of corruption are confident about their ability to report it, corrupt individuals cannot hide behind the wall of silence.

Proponents also argue that it is also equally important, for the whistleblower legislation to guide as much as possible the identity of the recipient of the report of the suspected corrupt act by the whistleblower.

In simple terms, the whistleblower legislation must be clear on the recipients of the reports.

In Zimbabwe, legal practitioners, the Auditor-General, the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission, the Zimbabwe Republic Police, Office of the Speaker of Parliament, the National Prosecuting Authority, the Gender Commission, the Human Rights Commission, the Judicial Service Commission, the Public Service Commission, the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission, employers and other bodies (non-statutory), should at least be allowed to receive the report by the whistleblower.

Furthermore, new international standards for whistleblowing remain in development across a number of jurisdictions and the country should not be seen lagging too far behind.

Comments