We’re black and poor, but we can write history!

A picture says a thousand words. Yesterday, we were confronted with pictures of an unwell Morgan Tsvangirai, leader of the opposition MDC-T or MDC Alliance. Mr Tsvangirai, who was diagnosed with colon cancer two years ago and has been battling the condition bravely, is not looking his healthiest.

The many pictures that we saw on mainstream and social media told us stories, in many thousand words. These are words that fed into a debate that is now raging — with renewed fury — about the leadership and succession question in the opposition camp.

Before we go a bit into the substance of the debate (for this is not the focus of this piece), we must say that we sympathise, unreservedly, with Mr Tsvangirai for the predicament that he is in, since cancer is such a deadly and costly affliction. Even the hardest of hearts would be touched by the state of malignancy that a cancer could land a person. But we are not doctors.

Neither are we gods – to whom we leave the health of one of the most notable men in the land. The debate in the country now revolves around Mr Tsvangirai’s health and his fitness to continue holding office of the president of the MDC-T (or Alliance, whatever).

Many of our ordinary eyes – though uncircumcised in the science of modern health – are quick to judge. They are diagnosing Mr Tsvangirai as unfit to run the coming race for national leadership, beginning with a gruelling campaign process and hopefully running office, if he wins.

Already, he has been on an extended compassionate leave as he fights the deadly condition and in between he has travelled to and from South Africa for treatment. The hope, and millions of prayers by Zimbabweans, is that he gets better.

In December 2016 Mr Tsvangirai, trying to quash rumors and worries about his health, declared himself fit and stated: “If we can defeat cancer we can defeat Zanu-PF. I am feeling very healthy now and I am confident that we are going to win the 2018 elections. That is the tricky part of Mr Tsvangirai’s health: it is both personal and political.

Pathetic historiography

We have indicated above that the state of Tsvangirai’s health is not the focus of this piece. Tsvangirai is part of a rather troubling debate we are about to discuss: the pathetic state of Zimbabwe’s historiography, which should not be allowed to continue any further.

Historiography is the study of the writing of history and of written histories or simply, the writing of history. Tsvangirai is part of Zimbabwe’s modern history – the history of the past 20 years, especially when he turned the wave of socio-economic disgruntlement into militant labour unionism that morphed into a political tide.

At the turn of the millennium, Zimbabwe was groaning under huge problems born out of the economic structural reform experiments of the Bretton Woods institutions, droughts, landlessness, poverty and hunger. The labour movement, represented by the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions, was at hand to harness the growing national discontent and led nationwide protests against Government.

A broad-based movement made up of labour, students, church — the civil society — and political activists emerged and culminated in a convention that resolved to constitute a political outfit that would give expression to, and address, the collective concerns.

This is not to discount some external forces that would soon be accused of hijacking the cause. Tsvangirai, secretary general of the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions, was the man who stood out as the natural leader of the growing movement.

The political outfit that came out on September 11, 1999 became known as the Movement for Democratic Change and it ushered in a new era of politics in Zimbabwe characterized by fierce contestation for space and power in the country’s body politic.

It was the MDC that brought Zimbabwe sharply into global focus, although for reasons and methods that some of us would never agree with. Tsvangirai was at the centre of it all. His high point came when, after nearly winning the Presidential elections and defeating then President Robert Mugabe in the 2008 elections, he became Prime Minister of the so-called “power-sharing” inclusive Government in 2009.

The inclusive Government ended in 2013 when Tsvangirai was beaten clean by Mugabe, leading to the decline of the opposition. It would seem the political health of the MDC was linked to the health of its leader.

At least in the short term.

The Tsvangirai generation.

A lot happened in between this history of the post-colonial, post-2000 Zimbabwe which Tsvangirai stars (and is a villain, too) prominently.

We can write this history.

We can write because it is fresh.

Happily, Tsvangirai himself wrote a book, At the Deep End, which is his biography published by South Africa’s Penguin in 2011. Perhaps, he imagined, just in time for the next step of becoming the President of the Republic!

Clearly on the sunset of his career, we hope he can write another. Or someone can – as indeed they should.

Waiting for Mugabe’s book

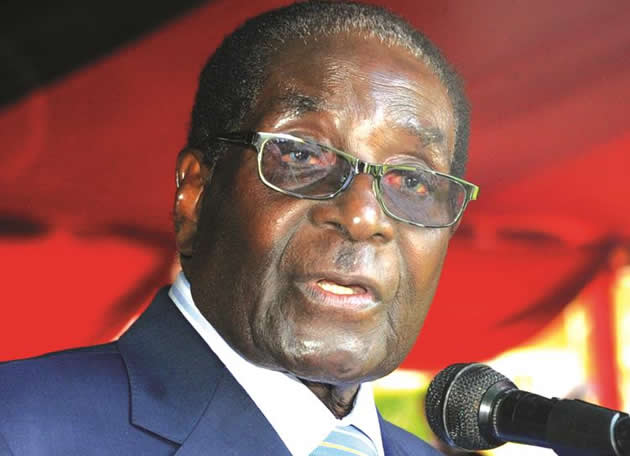

The wait has been long and unfruitful for a book by or on the former President of Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe.

It’s a common lament that we have not had a book — not just yet — about the former leader by himself, which one would have expected for the simple reason that he is a man of, and who knows so much history. He would have produced a book, or a paper at least, in a major phase of his life and the country:

l Robert Mugabe: political awakening”.

l“Early Nationalism in Rhodesia and Liberation Movements”.

l“Armed Struggle and the Lancaster House Agreement”. “Zimbabwe’s Early Independence, Conflict and Unity”. “Zimbabwe, Britain and the Land Question”.

l“Goodbye, Big Josh: Tribute to Joshua Nkomo (by Robert Mugabe)”

l“Mugabe against the World: A Reflection on Western isolation of Zimbabwe”.

l “Robert Mugabe: Working with Morgan Tsvangirai”

These are mere hypotheses and we are sure that historians may even find some of these propositions quite useful.

As indeed Mugabe himself.

It’s never too late.

It would be a serious aberration if we ended up without a book — and a best-seller too — that is not written by Mugabe himself or someone close and authoritative enough and we all remain with some histories written by some far away people.

Like Heidi Holland. Or Martin Meredith. Or Peter Godwin. It is such an indictment on our historiography, our historians, our journalists and not least the subject that is the man himself.

Perhaps the problem is bigger and more structural: is the environment conducive to writers, independent thinkers and researchers? Are people given access to subjects and personalities of our history? Are writers free after publishing? Who mediates our stories? Does anyone become an enemy simply for seeing differently from the status quo?

A lived story that must be written

A fairly experienced journalist can write the story of Morgan Tsvangirai because of its historical immediacy — and in general the post-2000 politics. Much better, one can write about the transition that we are in following the ouster of Mugabe via the assistance of the military under “Operation Restore Legacy”.

We witnessed the events of November. We are witnessing and experiencing the transition and change from nearly four decades of Mugabe’s rule. Astute writers should never have waited for a cue to write and record for posterity. Duty should have been the cue. Up to now, every day is a story. Every day is a history.

A common fear is that for all the experiences of the past 60 days which our writers, journalists and historians have lived, from the day then Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa was fired from Government to this day, it will take a white man from England to write for us.

Such a shame!

Such a burning shame!

The reality is that history has both the positive and negative sides; the glow and glum; the victories and losses; the beauty and blight…and so on. We should not be afraid to capture this history — our history – warts and all. It cannot be wished away.

Besides, writing should be a duty to the future because it is not for us to enjoy or gloss over issues. It is for posterity, which we owe the truth! We are not white people. We are poor. But we must write our lived history.

Journalists and writers would feel challenged by a statement often attributed to George Orwell that, “Journalism is printing what someone else does not want printed: everything else is public relations.”

Comments