Venezuela’s ‘humanitarian crisis’ and its US origins

Roger Harris Corespondent

A New York Times headline screams “As Venezuela collapses, children are dying of hunger”.

Lurid pictures show dead infants. A companion “article of the day teaching activities” asks: “Why do some young children choose to live on the streets instead of at home with their families?”

The key to understanding the wellspring of the Times’ indignation about humanitarian issues confronting Venezuela is hinted at in the by-line to the article: “Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world.” The stakes are high for the US empire.

The back story is that the Times and the rest of the corporate media have cheered on US government policies that have contributed to the current grave situation in Venezuela, while obstructing solutions other than regime change.

Although the Times caterwauls about the Venezuelan president’s “drive to dictatorship”, the newspaper of record fails to support mediation between the current government and elements of the now demoralised opposition who are willing to accept an outcome short of regime change.

Rather, the Times blithely opines “No nation should have to suffer such a leader”.

Regime change in Venezuelan would only put into power an unpopular opposition with no plan or inclination to address economic recovery.

When the Venezuelan people went to the polls, as they did in the last two most recent elections, they supported the present Maduro government despite the difficulties that the Times so melodramatically cherry picks. The voters knew survival would be worse under the US-backed opposition.

Challenges of the Venezuelan Economy

While there is no denying the economic emergency that Venezuela is currently facing and the concomitant suffering it is causing its people, understanding its context is essential to seeing a way out.

After a string of oligarchic governments dating back to 1959 and the neoliberal economic collapse and deterioration of living conditions for working people in Venezuela of the 1990s, Hugo Chávez was elected president in 1998. He instituted measures, which displeased Washington and its sycophantic press:

• Using Venezuela’s vast oil wealth for social programmes, rather than enriching the rich.

• Promoting an independent foreign policy, while creating regional alliances.

• Encouraging and empowering popular participation in the affairs of state.

A coup in 2002, backed by the US and cheered by the Times, failed to remove Chávez.

Instead, Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution enjoyed spectacular successes as it openly declared itself socialist, a term anathema to the US government and its corporate media.

Poverty rates were reduced in half; extreme poverty rates were cut even more. Community radio stations, communes, and cooperatives were created.

Well over a million homes were built for the poor. Regional alliances, excluding the US, came together. And the majority of people affirmed and reaffirmed what has become known as Chávismo in election after election.

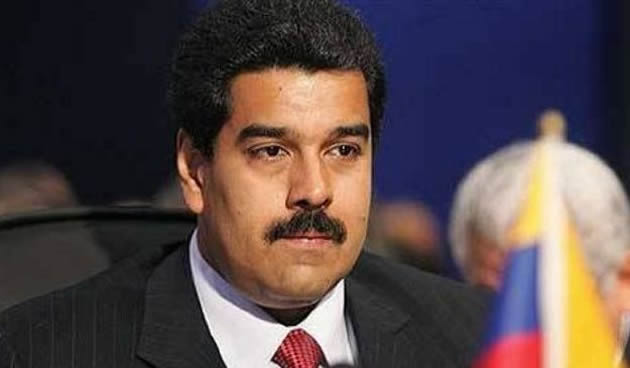

Then in 2013 Hugo Chávez died, and his successor Nicolás Maduro became president of Venezuela in a closely contested election. Maduro inherited not only the mantle of Chávismo, but a constellation of challenges that would have plagued Chávez himself had he continued: widespread and deeply ingrained corruption coupled with bureaucratic inefficiencies, a dysfunctional currency system, and an ingrained and recalcitrant criminal element.

Further, Chávez had granted amnesty to the perpetrators of the 2002 coup. These same “golpistas” are now among the leadership of a violent opposition to Maduro. What appeared to be a gracious gesture in 2002 has come back to plague and threaten the very existence of the Bolivarian Revolution.

Yet all these challenges to the success of the Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela pale in significance compared to two cataclysmic external factors.

• The social programmes that Chávez had instituted as well as aid to other countries had been subsidised by an oil commodity boom. Meanwhile, the costs of the existing inefficiencies and corruption were partly obscured in an economy flush with petrodollars. Then the bottom fell out of the oil market.

• Last but by no means least has been the enduring hostility of the US empire, promoting, funding, and emboldening both the internal opposition and Venezuela’s international opposition such as US client narco-states Colombia and Mexico.

The result is that, despite bold measures, the economy and by extension living conditions in Venezuela continue to trend downward.

The Times in Service of the US Empire

In an unbroken trajectory, the US empire has worked to overthrow the Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela from its inception. George W. Bush tried to depose Chávez in the failed military coup of 2002. His successor, Barak Obama, declared Venezuela “an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States” and imposed sanctions on Venezuelan officials. Now Donald Trump has echoed Obama’s nonsense about Venezuela posing a national security threat to the US and doubled down with new sanctions and even threats of military intervention.

The US policy is not based on mutual respect for national sovereignty and the rule of international law, but aimed at regime change in Venezuela. The Times and the other corporate media are mouthpieces for this policy. While crying crocodile tears about the suffering of the Venezuelan people, they support policies that relentlessly exacerbate human misery as a means of undermining popular support for the Bolivarian Revolution. These media are the promoters of the very conditions that they hypocritically claim to be opposing.

The recent US sanctions are designed to prevent economic recovery in Venezuela. The sanctions cut off needed access to international credit and block the Venezuelan government from restructuring its debt. US President Trump’s executive order in August, which barred dealings in new debt and equity issued by the Venezuelan government and its state oil company, has frozen over $3 billion in Venezuelan assets.

Some of the consequences of the economic war against Venezuela, are:

• Funds were frozen for the import of insulin, even though Venezuela had the money.

• Colombia blocked a shipment of the anti-malaria medicine Primaquine.

• Payments were suspended to foreign suppliers for three months holding up the arrival of 29 container ships carrying supplies needed to process and produce food products.

These recent developments synergise with the ongoing economic war by the traditional oligarchy in Venezuela, which takes the form of withholding goods from the market to create shortages, trafficking in contraband, and manipulation of the currency.

While hurting the people, the irony of the US sanctions is that they have bolstered the popularity of the Maduro government and exposed the complicity of the opposition.

All the Fake News That’s Fit to Print

A Times video, “Strongmen who’ve started blaming ‘fake news’ too”, fingers the corporate media’s usual suspects: Russia, Iran, China, and Myanmar.

Highlighted among the “strongmen” is Venezuela’s President Maduro, who is mocked for thinking that “fake news was part of a Western conspiracy to hurt his country”.

The Times self-servingly attempts to rebut Maduro, claiming that surely his view cannot be the case because the very news that Maduro criticizes is from the US, which has “a free and vibrant press”.

In short, the Times laments the consequences of the policies it supports, while opposing solutions short of regime change. The hostility of the Times to the Bolivarian Revolution is not predicated on humanitarian grounds. If it were, the Times would be defending its gains rather than polemicising for a neoliberal counter-revolution.

The Venezuelans should be allowed to solve their own problems. The responsibility of the US citizenry and its press alike should be to oppose interference by our government, which translates to no sanctions and no meddling in Venezuela’s internal politics. – Counterpunch

Comments