Unlearn learned helplessness

Arthur Marara

Point Blank

In 1967 American psychologists Martin Seligman and Steven Maier were conducting research on animal behaviour that involved delivering electric shocks to dogs in a chamber from which they could not escape (the non-escape condition).

The dogs in the escape group could escape the shocks by pressing a panel with their nose. In the second phase, the animals were placed in shuttle boxed divided by a barrier in the middle that the dogs could jump to escape the shocks. Only the dogs that had learned to escape in the previous phase tried to jump.

The other dogs did not.

When the dogs in the non-escape condition were given the opportunity to escape the shocks by jumping across a partition, most failed to even try; they seemed to just give up and passively accept any shocks the experimenters chose to administer.

In comparison, dogs who were previously allowed to escape the shocks tended to jump the partition and escape the pain.

What is learned helplessness

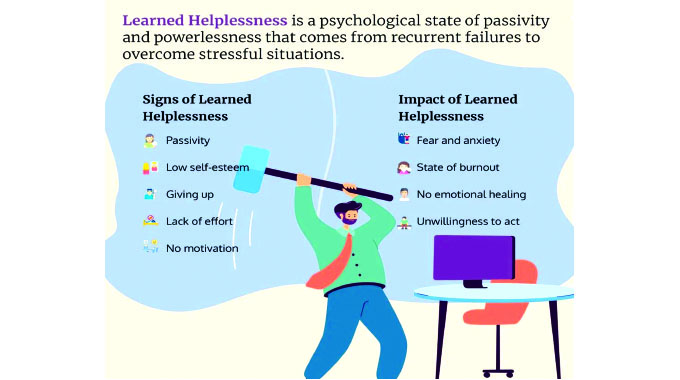

Learned helplessness occurs when an individual continuously faces a negative, uncontrollable situation and stops trying to change their circumstances, even when they have the ability to do so.

If a person learns that their behaviour makes no difference to their aversive environment, they may stop trying to escape from aversive stimuli even when escape is possible.

Learned helplessness also arises also when a person is unable to find resolutions to difficult situations — even when a solution is accessible. People that struggle with learned helplessness tend to complain a lot, feeling overwhelmed and incapable of making any positive difference in their circumstances.

The perception that one cannot control the situation essentially elicits a passive response to the harm that is occurring.

People become so used to their situations and give up the power to change them even when they can actually change. There are many people who have stopped trying to turn their businesses around because they tried and failed in the past. They are trapped in the memories of the past.

Learned helplessness is about responses to failure and not success. It is a control problem and not a competence problem?

Are you going through this in your life now or seeing it in your business?

How do we learn to be helpless?

Seligman subjected study participants to loud, unpleasant noises, using a lever that would or would not stop the sounds.

The group whose lever would not stop the sound in the first round stopped trying to silence the noise subsequently — even though the aversive stimulus was now escapable. Not trying leads to apathy and powerlessness, and this can lead to all-or-nothing thinking.

Learned helplessness can affect your life in all sorts of ways — none of which are particularly encouraging. The good news is that it is possible to “unlearn” learned helplessness. Working with someone who can help you recognise these patterns can be a huge step forward in learning something new.

How to unlearn learned helpless?

In his course on positive psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, Martin Seligman shares an anecdote from the original learned helplessness experiments.

While a certain percentage of people predictably became helpless in the face of uncontrollable events, some people — about 10 percent — seemed immune to the effect.

“These people,” Seligman recalled, “could not be made helpless no matter what.”

Resilience

There is a lot to learn from these resilient people. What is it about this “no matter what attitude; that makes people immune to learned helplessness?

Seligman’s partner, Steven Maier, found evidence that the dogs were not actually learning helplessness. They were failing to learn control.

As the neuroscience indicates, our brains are wired to panic under pressure (hello, fight-or-flight response). However, Maier discovered that there is a part of the brain that jumps in to regulate this response when it assesses that the situation is under control. With learned helplessness, that controllability mechanism never kicks in. You do not perceive that you are in control, and so, paradoxically, you are less able to exert control.

Learned optimism

Seligman also identified another component of the equation — learned optimism. It is essentially the polar opposite of learned helplessness, where you internalise a sense of hopelessness about your circumstances. With learned optimism, you begin to challenge your thought processes — and as a result, change your behaviours and outcomes.

Fortify your self-efficacy and internal locus of control.

There are two critical aspects of mental well-being – self-efficacy and internal locus of control. Self-efficacy is your level of confidence that you can tackle challenges and learn new skills.

Internal locus of control is the degree to which you believe your circumstances are under your control. When these two traits are high, you feel confident and empowered, even when things get tough. Stressors seem controllable, and you know that you can trust yourself to do your best.

When learned helplessness takes over, though, you do not feel so sure of your ability to handle challenges. You do not believe that what you do makes a difference, and that makes it hard to see a way out — let alone a silver lining.

Work on your belief systems

You know the story of the “Elephant and the rope”? A gentleman was walking through an elephant camp, and he spotted that the elephants were not being kept in cages or held by the use of chains.

All that was holding them back from escaping the camp, was a small piece of rope tied to one of their legs. As the man gazed upon the elephants, he was completely confused as to why the elephants did not just use their strength to break the rope and escape the camp. They could easily have done so, but instead, they did not try to do so at all.

Curious and wanting to know the answer, he asked a trainer nearby why the elephants were just standing there and never tried to escape.

The trainer replied; “when they are very young and much smaller we use the same size of rope to tie them and, at that age, it is enough to hold them. As they grow up, they are conditioned to believe they cannot break away. They believe the rope can still hold them, so they never try to break free.”

The only reason that the elephants were not breaking free and escaping from the camp was that over time they adopted the belief that it just was not possible.

No matter how much the world tries to hold you back, always continue with the belief that what you want to achieve is possible. Believing you can become successful is the most important step in actually achieving it.

Arthur Marara is a corporate law attorney, keynote speaker, corporate and personal branding speaker commanding the stage with his delightful humour, raw energy, and wealth of life experiences. He is a financial wellness expert and is passionate about addressing the issues of wellness, strategy and personal and professional development.

Arthur is the author of “Toys for Adults” a thought provoking book on entrepreneurship, and “No one is Coming” a book that seeks to equip leaders to take charge.

Feedback: [email protected] or Visit his websitewww.arthurmarara.com or contact him on WhatsApp: +263780055152 or call +263772467255.

Comments