Tuku files: Humanising the superstar

Stanely Mushava Literature Today

While Mutamba has the material to premise his judgments on, his heavily editorialised narrative does not present Tuku the human as opposed to the saint, but the convict as opposed to the human.

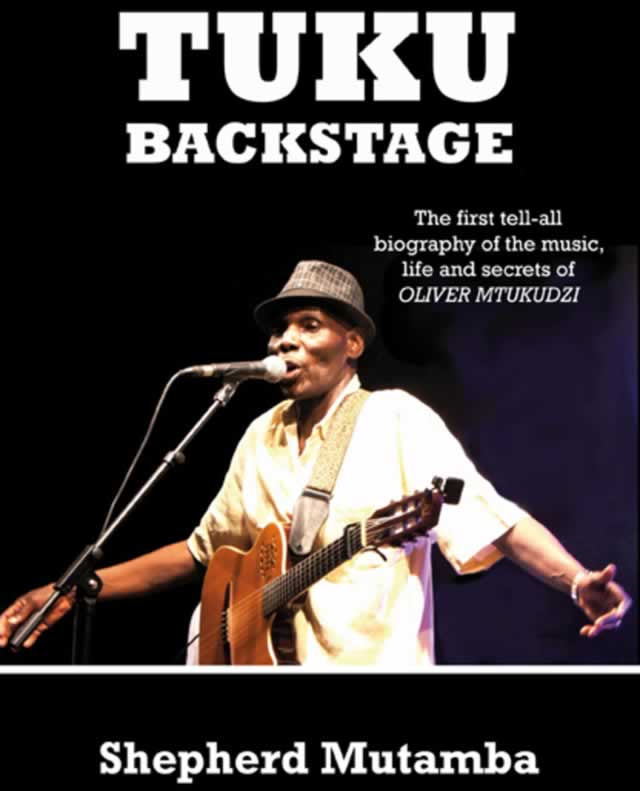

Book: Tuku Backstage

Author: Shepherd Mutamba

Publisher: Mhotsi Uruka

ISBN: 978-0-7974-6211-2

When discussing Oliver Mtukudzi, it is not necessary to look up superlatives: the name autonomously signifies brand value.

Four decades of Tuku Music are enough to form impressions about the man who evolved from an obscure ghetto artiste to Zimbabwe’s foremost cultural brand.

In 2004, Tuku ranked 69th on New African magazine’s “100 Greatest Africans of All Time,” ahead of the Queen of Sheba, Janan Luwum and Desmond Tutu, and fellow music notables Hugh Masekela, Salif Keita, Brenda Fassie and Manu Dibango.

The list, based on votes for African greats across colour, vocation and dispensation featured only two other Zimbabweans, President Mugabe and the late Vice President Joshua Nkomo, along with such greats as Samora Machel, Frantz Fanon, Bob Marley and Pele.

An institution apart, Tuku is, without controversy, the face of the Shona Renaissance, as he has done more than any other artiste or intellectual to export the beauty and lore of the mother tongue across the world.

The danger with being such an immense figure, however, is that people want to place you on a pedestal and canonise, not just as an artiste but as a living saint.

That has happened with Tuku. What we know of the man is largely an airbrushed stage persona, enhanced by the philosophical piety of his music.

“Tuku Backstage,” a 2015 biography by Tuku’s former publicist, Shepherd Mutamba, navigates the divide between the man and the performer.

Regrettably, Mutamba not only sets out to drag Tuku out of his closet; he savages him with vengeance.

For me, any biography must be judged on three fronts: the magnitude of the subject, the exclusive range of the narrative and the critical facility of the writer.

Mutamba is covered on the first two fronts, but falters on the third front.

No one can impugn his objective to present us with a close-up portrayal of a man we revere.

He also does a good job of synthesising exclusive details from Tuku’s private life, relationships, scandals and creative processes in a way no one has done before.

We get to learn that the consistent champion of family values is badly compromised.

Predictably, reception of the book has made much of Tuku’s alleged promiscuity, negligence of children from his first marriage, mistreatment of workers and subservience to a henpecking wife, caricatured into a kind of Lady Macbeth in the book.

However, grievances from Mutamba’s relationship with his former employer weigh unnecessarily on his portrayal of his subject.

In fact the blurb announces a not so objective agenda: “The writer digs into Tuku’s intensely private life, revealing what is held about his dreadful ways… debauchery, neglect and affection.”

While Mutamba has the material to premise his judgments on, his heavily editorialised narrative does not present Tuku the human as opposed to the saint, but the convict as opposed to the human.

The singular verdict in the blurb and the conflict of interest occasioned by a professional fallout becomes a frame for what is to follow. Mtukudzi can well present “Chipembenene” as his heads of argument.

There are parts of the book I wish Mutamba had not written.

In the opening chapter, he unnecessarily digresses from Tuku to his own political biases and sexual fantasies.

Although he writes to forestall criticism in the preface, insisting that: “I must write my thoughts and obey only my mind because creativity is my right,” one wonders why some of the crude passages in the book add value to the narrative.

In such instances, Mutamba seems to be writing under the Bill Saidi Syndrome as he competes for space with his subject.

The biographer is not indulgent of weakness. His summation of Tuku, from the outset, shows readers how to sing and how not to live.

He makes an incredulous claim that President Mugabe silenced Tuku with money for Sam’s funeral expenses, studio equipment for Pakare Paye Arts Centre, a birthday present for his 60th anniversary.

“The gifts were reciprocated when Tuku stopped all political criticism, satire and metaphor targeted at President Mugabe’s style of rule. That is what the president desired, and I am sure that he has been chuckling to himself ever since the day that he silenced our music icon,” Mutamba writes.

Mutamba is out of his depth with such commentary.

Besides ruling out the place for empathy, he seems to imply some kind of political duel between Tuku and President Mugabe, although that seems nowhere in evidence in real life.

Tuku’s music has always been something for everyone since his first hit, “Dzandimomotera,” 40 years ago. If some listeners have located political barbs in the music, it is because of its polysemy rather than an activist commitment on the part of the artiste.

Mutamba goes on to draw musical lectures out of his own assumption. “Artists who subordinate themselves to political whims cannot be the voice of the people,” he writes.

“We can now look up only to Thomas Mapfumo, who has not faltered on political criticism and resistance. That is why he will be remembered as a true hero of the people’s political struggle. They do not call Mapfumo the ‘Lion of Zimbabwe’ for nothing,” writes Mutamba.

The assessment is premised on an erroneous assumption that the artiste is a political functionary. For Mutamba to assume an artiste of Tuku’s stature must personalise his music against the political establishment of the day, appears rather odd.

It is surprising that Mutamba insists that: “I must write my thoughts and obey only my mind because creativity is my right” but seems to think that Tuku does not have the same creative autonomy to sing about the world as he interacts with it rather than from the perspective of an ephemeral political template.

Some reviewers have dismissed Mutamba as an aggrieved former employer taking a dig at his former boss.

There is some truth in that but a basic conclusion may obscure the nuggets in the book. Mutamba gives an engaging account of Tuku’s rise from obscurity to stardom.

Here is a man who used to sing his own songs to himself for inspiration when the going was tough; a man who used to travel in the boot of a cab in 1988, 13 years after his debut single, while mediocre brands ran the town.

Not only artistes but people from all walks of life will draw strength from this ghetto youth’s enduring commitment to his vocation when no one else seemed to believe in it and his eventual rise to global recognition.

A veteran journalist, Mutamba’s insight on art, enhanced by his exposure to big players in the industry are important reading.

Tuku’s breakthrough in 1998, is attributed to the scaling up of his workflow to global standards on the album “Tuku Music.”

Mutamba also shows that while Zimbabwe is rich in artistic talent, poor promotion and bad management is our worst undoing.

What to make then of the rift between Tuku the person and Tuku the person? I commend the superstar for lifting his music to the truth instead of bending it down to his weaknesses.

Most of Mutamba’s exclusive details correspond with Tuku’s songs.

His account of Tuku’s break-up with his first wife, for example, seems to be corroborated by the song “Waona.”

Comments