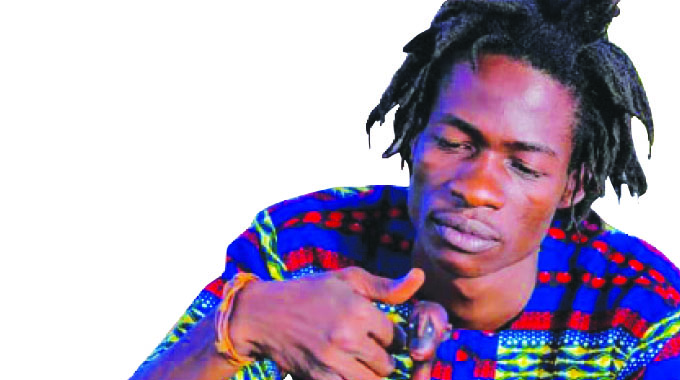

Tocky Vibes following Tuku’s footsteps

Onai Mushava Own Correspondent

If Van Choga is a drunken dragon on stage, then Tocky Vibes is an ecological event in the studio.

In the New Dispensation alone, Mr Vibes has released seven projects — five studio albums, an acoustic compilation and a singles collection — besides uploading videos more often than your crush’s photoshoots. But — though we could place Tocky Vibes against Van Choga’s energy or against Van Choga’s authenticity — one question makes more overall sense: Is Tocky Vibes the next Oliver Mtukudzi?

On his latest album, Dhongi neWaya, Tocky Vibes pays his second tribute to the late great Tuku.

The previous tribute was a collaboration with Soul Jah Love whom Tuku picked, along with Tocky Vibes, as his favourite young artiste.

Sung over “Shanda” and “Hear Me Lord” keys, “Mudhara Tuku” repeats advice from the African superstar to the 26-year old singer not to listen to people and, equally, advice to sing for the people and to sing for keeps.

Most gatekeepers will jump at any parallel between Tocky and Tuku as blasphemy, so we may well oppose a little mathematics and history to their piety.

As if it is not mathemagical enough working out how Tuku did 66 albums in 42 years — a yearly album for each of his 66 years on earth — Tocky casually drops four projects in 2019 alone.

At a conservative rate of three albums per year, Mr Vibes will have recorded 100 albums by the time he turns 60.

All creativity, no calculation

The immediate objection here would be: What sort of albums?

Talking greatness, Tuku is Zimbabwe’s answer to Bob Marley while the usual thing is to look past Tocky Vibes in the pop conversations of the day. But then a righteous parallel necessarily goes back in the day to pick up a Tocky-sized Tuku.

According to Tuku’s day-one, Piki Kasamba, in the 1980s, the Black Spirits was a second-tier band compared to Thomas Mapfumo’s Blacks Unlimited or Zexie Manatsa’s Green Arrows. Whereas fans micromanaged Winky D and Jah Prayzah albums down to the last conspiracy theory in the 2010s, Tocky Vibes albums like Tirabhuru/ Kwatazonke (2016) and Rori (2018) slipped past reviewers’ notice.

All creativity, no calculation makes Tocky Vibes a second-tier artist.

Whereas commercially attuned heavy-hitters spread their releases around charts and algorithms, Tocky Vibes works with his raw process in the open. The album title and tracklist for Rori were apparently changing in beta mode at the latest prompt, while the video rollout was unambitiously mixed with new singles.

His weaker albums, including the latest one, lack a sense of cohesion and the song selection is thin on stand-out moments. Occasional masterpieces are left as loose singles while the ones that make the album get diluted in a sprawling tracklist.

And then his best work — Chamakuvangu (2018) was by far the album of the year in my book, and Villagers Money Vol. 1 (2019) is a good-to-great effort — comes and goes without a mainstream splash. So the good things we know about Tocky Vibes — originality, versatility, vocal range, penmanship and so on — hardly cohere into one premium package.

No industry for young men

This would not be unfamiliar territory for Samanyanga. We know all the great Tuku songs because he endlessly reprised and reissued them. For example, he released no less than six retrospective compilations since Derby Metcalfe famously took over dragged him after the bag. But how many kept the same energy with the albums his classics arrived on: Nzara (1983) or Was My Child (1995) or Ndega Zvangu (1997) for example?

Can I make a side note here for a second? How many people confuse creativity and visibility, or rather art and business, when it comes to assessing the Tuku legacy.

Some claim that Tuku became great after sungura icons fell to Aids, some claim that Tuku became great after Metcalfe over, some claim he became great after Thomas Mapfumo left for the US. No; I am not buying any of that. Tuku the album artist does not become great in 1998; he is already great in 1978.

To prove that he was always great but we just did not notice, he released as many compilation albums as he released new albums in the 2000s, when he finally had all eyes on him, and each release solidified his status home and away.

In other words, he was playing us for not having played him. Still other words, he had been deepening and broadening all along and now he was rising.

It is not hard to picture Tocky Vibes on a major-label compilation few years from now, making you write a PhD about songs you skipped in 2017.

Tocky got nothing on the younger Tuku when it comes to being creatively dope and commercially questionable. Mudhara Piki recalls an era when the Black Spirits played for passion while living hand to mouth, somewhat confirming biographer Shepherd Mutamba’s recollection of a pakadoma encounter with Tuku a decade after the legend had already sung revolutionary classics.

It is said that an elephant is not weighed down by its ivory but the weight of a band sometimes got too much for the younger Samanyanga.

He would wake up without a band and play through the bad days out of sheer self-belief. Sugar Pie (1988) was reportedly recorded solo, with Tuku playing everything in turn. On Ndega Zvangu (1997), Samanyanga goes toe-to-toe with Steve Makoni for album-length guitar solos, a formula nowhere near the epoch-making Tuku Music that comes a year on.

Wawona (1987) is recorded with a borrowed Zig Zag Band after a band exodus and the gospel album Ndotomuimbira feels like a lonely afterthought.

Chamakuvangu equally knows few things about going it alone.

In 2015, he reportedly fired his band for incompetence just before a Kwekwe show and then asked organisers how on earth they expected him to perform without a band.

His glory days were just behind him after ditching riddims to explore his own sound.

As showbiz panned to the next trend, Tocky Vibes was dropping career meditations like “Muroyi” and “Bhora Mutambo” in frequent batches of singles that will only make sense in retrospect.

Tuku made vulnerable music too at his lowest, special art to be related with differently from sonically accomplished but spiritually detached songs that entertainers do in their peak years.

Onai Mushava is the editor of Jikinya.com

Comments