The struggle of values in ‘Secret Lives’

Elliot Ziwira The Book Store

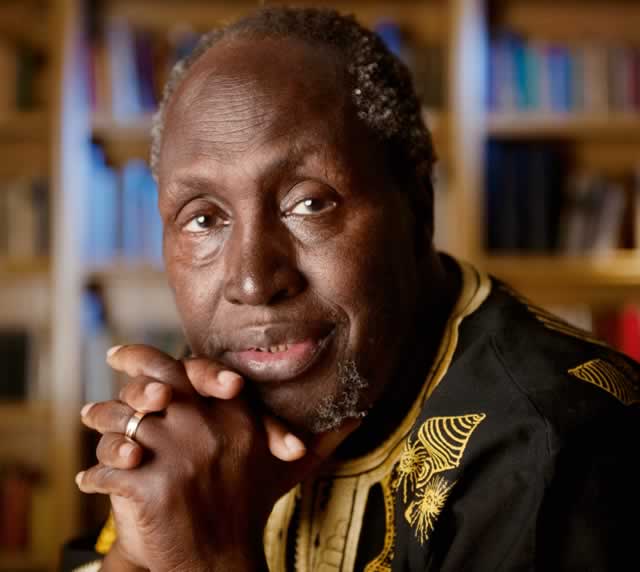

Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o compellingly tells the African story from a vintage point using a combination of wit, humour and contempt.

He visits the African experience from the colonial state, through the struggle against displacement and imperialism to the post-colonial era in “Secret Lives and Other Stories” (1975).

By combining different epochs, and bringing them to the boil using powerful images and symbolism, Wa Thiong’o metaphorically evokes the sombre, bizarre and frustrating outcomes of the African story.

As a story-teller, his strength lies in his narrative skill, as he skilfully combines different voices, which hoists the reader right into the core of existence in the face of adversity.

As is the case in “The Trial of Dedan Kimathi” (1975), the writer travails into the history of Africa, as it groans under the weight of colonialism and desperately clings to hope.

Using the metaphors of drought, hunger and rain, like Charles Mungoshi and Dambudzo Marechera, in “Waiting for the Rain” (1975) and “House of Hunger” (1978) respectively, Ngugi wa Thiong’o taps into folkloric tradition to capture the rich African culture before the advent of colonialism and the Christian God.

Borrowing heavily from different modernist traditions; realism, impressionism, romanticism and naturalism, the book can be read as pastoral, historical, gothic or proletariat. The African story cannot really be told in a better way.

Divided into three parts; Of Mothers and Children, Fighters and Matyrs and Secret Lives, the book, traces the nature of Man and his struggles against himself, his fellow men and his environment.

Through adept use of imagery and symbolism and deliberately long paragraphs, the movement of the fictional experience is subdued as the writer prolongs the burdensome existence of the common man in a world that trivialises his suffering.

In the stories “Mugumo”, “And the Rain Came Down!” and “Gone with the Drought”, which are in the first part, metaphors of drought, barrenness and rain are used to capture the burdens of womanhood and motherhood as women try to circumvent societal expectation.

“Mugumo” explores the sensitive issue of barrenness through a young woman, Mukami who falls in love with Muthoga; “the warrior, the farmer, the dancer”, who already has three other wives, much to the chagrin of her father. Her momentary happiness, however, is dampened by her barrenness as she is unable to give her husband a child after four seasons of marriage.

Her misery is compounded by her husband’s violent nature which was once subdued by his love for her. Tired of “the beating; the crowd that watched and never helped”, she seeks flight from both the physical and psychological sites of her existence.

Although wa Thiong’o does not condone societal mischief and the chauvinistic nature of men, he advocates the summoning of divine intervention as a way of consolidating the marriage institution for the sake of regeneration and peace. In “Mugumo” societal and individual biographies are merged through effective exploitation of the metaphors of rain and barrenness.

Barrenness, like drought, evokes feelings of hopelessness and lack central to both societal and individual discourses. Mukami’s barrenness mingles with the motif of waiting pervading the story to create a universal feeling of expectation which drives it. The protagonist’s decision to seek solace in the valley of the dead which invokes gothic elements and her subsequent consultation of the divine under “the sacred Mugumo – the altar of the all-seeing Murungu” ignites the fire of hope, not only for her but the entire community.

As the rain pours down on her in torrents, Mukami’s metamorphosis begins, right under the sacred tree as she feels something kicking in her womb. Realising that she is pregnant, “and had been pregnant for sometime”, she resolves to go back home because: “That was her rightful place, there beside her husband amongst the other wives. They must unite and support ruriri, giving it new life”. Rain, therefore, is symbolic of hope, abundance and regeneration, so like drought, barrenness can be cured through divine intervention.

This rationale of the invocation of the supernatural in the face of hopelessness also obtains in “And the Rain Came Down!” The metaphors of drought, barrenness and rain are also used effectively to consolidate the writer’s intention of absolving human folly through the divine route.

Womanhood is burdensome in a society that only thinks of women as vessels that should carry societal baggage on their shoulders. Without children a woman is incomplete as society sneers at her; singling her out for scorn.

Yet motherhood does not only come through child-bearing but the responsibility brought on women by nature. Nyokabi, the heroine in the story, has always dreamt of marrying and having “so many” children, but unfortunately her womb cannot yield to her desires.

Weighed down by frustration, scorn and jealousy, she hates all women with children, and especially her friend Njeri. For years she has not seen her or congratulates her on any of her deliveries.

Riven by desperation and age, she wonders into the depth of the forests to seek salvation. As she pours out her sorrows, it begins to rain heavily and she desperately clings to the hope of death that she espies.

However, death does not come her way for there is no hope in dying; instead she hears the shrill cry of a child. Gnawed by jealous “to save another’s child”, her motherly instincts propel her to where the child is. Forgetting all about her near exit from sorrow through death, she shields the child from the vagaries of nature and takes her home.

Ironically the child turns out to be her friend; Njeri’s who eluded the other children. Although she does not know it as she immediately drops into retired slumber, her husband who knows the child is so proud of her for saving the child.

In the second and third parts of the book, Ngugi wa Thiong’o lashes out at religious and political intolerance and hypocrisy as it is detrimental to constructive reasoning. The metaphors of drought and barrenness that permeate the first part find home here as the nation awaits a new era of hope from the colonial shackles that burden it.

However, without an authentic national discourse premised on traditional values, hope remains a mirage. For Africa to remain relevant to its people traditional African religion should be allowed to triumph. In the stories “The Village Priest” and “The Black Bird”, the religious turf pitting Christianity and African Religion takes an ugly outlook.

“The Village Priest”, Joshua, who is initiated into Christianity by Livingstone, a white missionary, promises the desperate community rain through prayers to his Jehovah. The rain-maker who is the interceder between the living and the dead, tells the people that it will rain after the traditional rites under the sacred Mugumo tree.

Hilariously, Joshua prays against the rain on that particular day, so that his God wins against the God of his people. He yearns: “Please God, my God, do not bring rain today. Please God, my God, let me defeat the rain-maker today, and your name shall be glorified.”

As a story-teller of note, Ngugi wa Thiong’o in “Secret Lives” (1975) as in “Devil on the Cross” and “Matigari” captivatingly conjures sad images of a continent that lies prostrate as it is repeatedly raped, not only by imperialists and their machinations, but by its own political demagogues who prey on their own people using their ill gotten wealth and Christianity to hoodwink them.

Comments